A full-length statue of Karl Marx has been inaugurated by the Chief Minister of Tamil Nadu in the Chennai Connemara Library. Criticising this, Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) leader Tamilisai Soundararajan asked: “They are putting up a statue for Karl Marx. Even the Communists themselves have forgotten him. What connection does Karl Marx have with Tamil Nadu? Did he ever come here?”

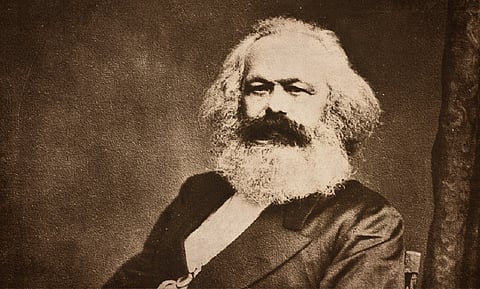

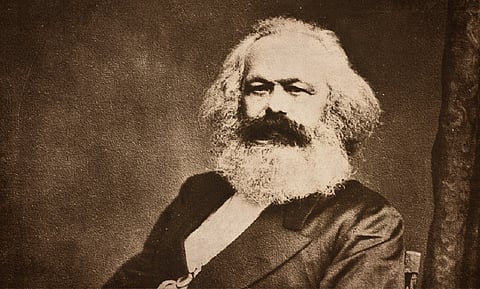

Before erecting a statue for any personality, one must first consider whether they are worthy of such honour. By that measure, Karl Marx possesses every qualification. Revolutions inspired by his ideas in many countries across the world in the twentieth century liberated millions of people. No one else has scientifically demonstrated as convincingly as he did how essential economic equality is for the progress of humankind. That is precisely why the Indian Constitution proclaims India to be a “sovereign, socialist, secular, democratic republic.” Since Marx proposed the ideas that the Constitution itself accepts, it is entirely appropriate to install his statue in Tamil Nadu.

Tamilisai’s question about what connection Karl Marx has with Tamil Nadu arises from ignorance for Marx wrote extensively about India, and specifically about Tamil Nadu.

Between 1853 and 1858, Karl Marx wrote thirty-three articles on India for the ‘New York Daily Tribune’. Notes he prepared on India in his later years were subsequently compiled and published as a book, Karl Marx: Notes on Indian History. In these notes, he wrote about Indian history from AD 664 to 1858 — covering Mughal rule, wars between the British and the French, and the exploitation carried out by the East India Company. These writings remain useful even today for understanding Indian history. Both his Tribune articles and his compiled notes contain his observations about Tamil Nadu.

In his articles on the Sepoy Mutiny, (Marx and Engels on the national and colonial questions - Selected writings, edited by Aijaz Ahmand) Marx discussed the findings of the British government’s Torture Commission. One of the incidents described in its report took place in Tamil Nadu.

“In 1854, Mr Danby Seymore, MP, accused the Company of using torture and coercion to get ten shillings from a man when he only had eight. Soon the British press took over. The Times wrote of the "Indian Inquisition" and Punch carried a satirical piece on the issue. The Court of Directors immediately directed the Madras Government to set up "a 'most searching inquiry' and to furnish them a full report on the subject." Accordingly, on September 9, 1954, a three-member Commission was appointed to enquire into the "use of torture by the native servants of the state, for the purpose of realising the Government revenue." However, the scope of the enquiry was soon enlarged to include "the alleged use of torture in extracting confessions in police cases" (Anuj Bhuwania’s Very wicked children: Indian torture" and the Madras Torture Commission Report of 1855)

This body, known as the Torture Commission, submitted its report in 1855.

On September 17, 1857, Karl Marx wrote an article in the New York Daily Tribune about the torture inflicted on Indians during the British rule. He quoted several portions of the Torture Commission’s report.

Most victims were tortured for non-payment of taxes, though other reasons were also cited. One case involved the construction of a railway bridge over the Coleroon ( Kollidam) River (in present-day Mayiladuthurai district). A Brahmin from Coleroon complained that the tahsildar had demanded planks, charcoal, firewood, etc. gratis, that he might carry on the Coleroon bridge work. On refusing, he is seized by twelve men and maltreated in various ways.

He adds, “I presented a complaint to the subcollector, Mr. W. Cadell, but he made no inquiry and tore my complaint. As he is desirous of completing cheaply the Coleroon bridge work at the expense of the poor and of acquiring a good name from the government, whatever may be the nature of the murder committed by the tahsildar, he takes no cognizance of it.”

Marx cited this testimony.

Torture, Marx wrote, was not an aberration but a routine practice of British rule. Describing its character, he stated in The Indian Revolt that torture was “an organic institution of its financial policy.” He also argued that the crimes attributed to Indians during the 1857 uprising were themselves a reaction to the way England had governed India.

Tamil Nadu appears not only in Marx’s journalistic writings but also in his historical notes, later published from Moscow after the Soviet Revolution. These contain over thirty references to Madras.

Marx recorded in detail the battles between British and French forces for control of the fort at Cuddalore.

He also referred to the Ramayana: “The Ramayana glorifies the exploits of Rama, King of Oudh; he is supposed to have lived about 1400 BC; according to the poem, he was the Hindus' conquering leader in the march on Deccan and Ceylon; in the course of that legendary invasion, the Hindus found in Deccan many civilized nations: Tamils speaking the Tamil language, and others in the Telinga (Sic) country, whose vernacular was Telugu. The most ancient kingdoms were the Tamil.”

Marx further noted:

“About the 5th century BC, Pandya was founded by a shepherd king of that name; small country; capital, the ancient town of Madura, and territory, the present districts of Madura and Tinnevelly in the extreme south of the Carnatic; remained independent till 1736 AD, when conquered by Nabob (SIC) of Arcot.Chola, where Tamil language spoken; in 1678, a Maratha chieftain, Venkoji, supplanted the King, and became the first of the present rajas of Tanjore.”

“The Chera country was a small state comprising Travancore, Coimbatore, and part of Malabar” he noted.

On languages of the Deccan, in his Historical Notes, Marx wrote:

“There are five languages in the Deccan: (1) Tamil, spoken in the Dravira (Sic) land, i.e., the extreme south, bounded by line running through Banga-lore, along the Ghats to Coimbatore and Calicut; (2) Kanarese, a dialect of Telugu, in North and South Kanara; (3) Telugu, spoken in Mysore and the countries to the north; (4) Marathi, written in the Devanagari alphabet and having the following limits: north, the Satpura Hills; south, the Telugu country, called Telin-gana; east River Wardha; west, the hills; (5) Oriya, a rough dialect spoken in Orissa. Between Orissa and the Maratha country are the Gonds, who speak a rough jargon.”

Marx also wrote about the Ryotwari land revenue system introduced by the British in the Madras Presidency:

“Ryotwari System in Madras, established by Sir Thomas Munro; first recognised as the basis of the revenue administration of the Madras Presidency; not permanently ordained till 1820. It functioned as follows: Revenue officers of the Government made an annual settlement early in year, when crops were sufficiently advanced to judge of their abundance and quality; at this time, the government tax equal-led one-third of the produce; the cultivator was held responsible for this tax, as assessed and inscribed in the pottah, or lease, annually granted to him. If failure occurred owing to accidents of climate, the whole village was ordered to be ratably assessed, to bear the burden of the tax upon the land which had failed; if such a failure [was believed to have come about by the wilful obstinacy of a ryot who, after having accepted the pottah, refused to cultivate his land, the collector had power to punish him by fine or even by corporal hastisement.

The collector, with his absolute power to withhold or grant the pottah, had during each year absolute control over each district.”

Karl Marx’s writings on Tamil Nadu span history, economics, culture, and politics. They acknowledge the antiquity of the Tamil language and the significance of Tamil kingdoms. Therefore, installing his statue in Tamil Nadu is appropriate not only because he was a great thinker who reshaped the world, but also because he was someone who studied, understood, and wrote in depth about Tamil Nadu itself.

D Ravikumar is a Member of Parliament (Lok Sabha) representing the Villupuram constituency in Tamil Nadu. He is from the Viduthalai Chiruthaigal Katchi (VCK) party.

Views expressed are the author’s own.