Do islands need ships?

At least one island administration — the one running Andaman and Nicobar Islands — doesn’t think so.

In 2016, it ordered four ships from Cochin Shipyard. Two of these, capable of lugging 500 passengers and 150 tons of cargo, were to ply within the archipelago. The other two, with an intake of 1,200 passengers and 1,000 tons of cargo, were to run between the mainland and Sri Vijaya Puram, as Port Blair has been freshly rechristened.

Work began. The first of these ships, MV Ashoka, was "on track for delivery" by the end of 2021. By August 2022, the second ship, MV Atal, was ready as well, and had to be outfitted with machinery and living quarters.

Payments from the administration had moved smoothly as well. Of the Rs 1,294 crore it had to pay Cochin Shipyard, Rs 819.22 crore were meant for Atal and Ashoka. By June 2023, sticking to the payment schedule, the administration had transferred 80 per cent of this amount.

By June, however, the Andaman administration had dropped a bomb. It didn’t want the ships.

Locals’ travel habits have changed, an unnamed official in the administration told Economic Times. “The island people who were totally dependent on water transport to travel to the mainland and back, are now increasingly using air transport for their travel needs, saving the 2-3 days required for journey by ship one way, as cheaper air tickets aided by government schemes force a change in their travel patterns,” the business paper wrote, quoting the official.

It was an extraordinary assertion. Not only had the administration backed away from ships it had already paid for, it was also ignoring island realities. “We had three ships — Nancowry, Nicobar and Swaraj Deep — that could carry 1,200 passengers,” an official in the administration’s Directorate of Shipping told this reporter. “Given a large earthquake, roads and runways will crack. These ships were very useful during emergencies. During the tsunami, these ships had been working heavily.”

Even in normal times, these ships are a critical lifeline. India’s shipping ministry doesn’t reveal passenger numbers for specific routes like Chennai/Kolkata/Vizag to Port Blair but the Directorate of Shipping official pegged Swaraj Deep’s capacity utilisation at 150-300 passengers in the off-season but 1,200 in the peak season. These numbers, however, are despite the ship’s poor maintenance. And then, there is cargo. “Vegetables for Andaman and Nicobar come from Chennai or Kolkata,” said the official. “Right now, we are getting potatoes at Rs 100 a kilo because the supply is not very good. If we have these big ships, all those transport problems would be taken care of.”

In addition, while ships do take 2-3 days to reach the mainland, they are cheaper and an alternative mode of transport. In peak season or at short notice, air tickets are either unavailable or they cost the earth — with prices above Rs 20,000, a hard ask for any islander family that needs to rush to the mainland. In contrast, a bunk in the ships between Port Blair and Chennai costs Rs 1,300 for islanders.

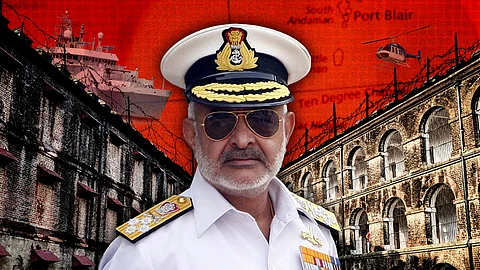

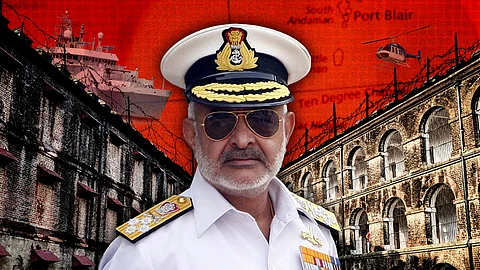

Despite such counter-arguments, the Andaman & Nicobar Administration refused to yield. It suggested the navy take these ships — a proposal opposed by the islands’ former MP. Thereafter, Cochin Shipyard tried selling these ships to Lakshadweep. That proposal went nowhere as well. According to Vesselfinder, both ships are now plying under unknown flags. It’s unclear if the Andaman administration recovered the Rs 819.22 crore it had paid Cochin Shipyard. The News Minute posed this question to Andaman and Nicobar Lieutenant Governor DK Joshi and Chief Secretary Chandra Bhushan Kumar. No answer had been received by the time this report was published.

Clearer, though, are the fallouts for islanders. Of the three large 1,200 seater ships plying between the mainland and the islands – MV Nancowry, MV Nicobar and MV Swaraj Deep – just one is left. “Nancowry and Nicobar have already been condemned,” said the official. “In two years, Swaraj Deep will be decommissioned as well. Once that happens, we will not have any big vessels. We will have to turn to private charters.”

This decision on MV Atal and MV Ashoka – which militates against islanders’ welfare – is not an isolated instance.

In recent years, the UT administration has also taken away panchayats’ power for local expenditure; underfunded healthcare; steamrolled projects like the Great Nicobar transhipment port despite objections from local communities; ignored local demands for industry-friendly policy; used transfers as a punitive measure to ensure compliance; hurt the islands’ indigenous people; one could go on. Put all these patterns together and you will see some central traits of the current UT administration: its inability to think like islanders; a wilful under-provisioning of services to the locals; recklessness with public finances; and an unwillingness to engage with local demands. These traits raise concerns about how the government's new infrastructure push on the islands will play out in practice.

Shadow of misgovernance

Hardwired into these decisions is a larger regression in the UT administration. The archipelago has little independent media, civil society or centres of political power, an arrangement which concentrates powers with bureaucrats, overseen only by the lieutenant governor, the chief secretary and the Home Ministry. In the past too, ergo, its administration has faced local flak for misgovernance and an obliviousness to island realities – like the insistence on building roads over investing in ships.

Even with that backdrop, what the islanders are seeing today is new. The UT administration is tilting even further in favour of itself, outsiders and large construction projects over the islanders—with a corresponding rise in intolerance towards criticism.

This drift has not received the attention it deserves. Like Lakshadweep, Andaman and Nicobar rarely make it to national headlines. Only eye-popping developments — like the tsunami of 2004; rape charges against a former chief secretary; or plans to build a transhipment port at Great Nicobar — get reported by the media. More local developments do not get the attention they deserve.

And yet, unlike the mainland, mis-governance casts a longer shadow on the islands. Given low population, few resources and geographic isolation, people here rely on the administration for basic needs like travel, employment, healthcare and housing.

When the administration turns truant, islanders’ lives get severely circumscribed.

Healthcare takes a back seat

From outside, the Primary Health Centre (PHC) at Campbell Bay looks adequate. It’s a single-storied structure which calls old government schools to mind — with rooms with asbestos sheet roofs lining a rectangular central courtyard.

On stepping inside, the initial perception starts to fade. Despite getting 120 to 150 patients a day, it has just two allopaths and a dentist, apart from one ayurvedic doctor and one homeopath. Despite locals still carrying scars from the 2004 tsunami, it doesn’t have mental health specialists. It has an x-ray machine but no ultrasound. Cows and stray dogs stray into hospital premises. As recently as 2020, patients in the general ward and the TB ward shared a common toilet.

That is just the start. This PHC is the apex health centre for all of Great Nicobar which has a population of just over 8,000 people. Patients it cannot handle have to travel 523 kilometres to Port Blair. This is easier said than done. Connectivity between Port Blair and Campbell Bay is erratic. The MV Sindhu, the sole ship between these two administrative centres, comes once a week. There is air connectivity, but between inclement weather, three-seater helicopters and ten-seater dorniers which also have to accommodate VIPs and passengers from Car Nicobar, flight seats are not always available. At Rs 5,350 per seat, they are also expensive.

Most households in Campbell Bay, a resident told The News Minute, earn between Rs 1.5 lakh to Rs 2 lakh a year — a monthly income of Rs 12,500 to Rs 16,600. Flights, ergo, used to be free for patients till three years ago. “But, for the last three years, both patients and nurses accompanying them have had to pay,” said a medical worker in the archipelago on the condition of anonymity.

For all these reasons, locals have been asking the administration to upgrade the PHC to a community health centre (CHC). “If it becomes a CHC, the centre will have a surgeon and a gynaecologist,” said the medical worker. “Campbell Bay can take care of patients here instead of sending them to Port Blair.” The hospital, added the medical worker, also needs to separate its TB ward from the rest of the hospital. In spite of all these reasons, the administration has not upgraded the PHC. “The administration says Campbell Bay’s population is very low — just 8,367 in the 2011 census — and so, it qualifies only for a PHC,” said the worker.

As responses go, this one is odd. The total population of Andaman and Nicobar is about 7 lakh — which makes it one of India’s smallest districts. Extending that logic, the archipelago should be governed by just one district collector. Instead, it has a veritable buffet of administrators — apart from the LG and the Chief Secretary, the archipelago has 17 IAS officers and 23 DANICS officers.

At the PHC, there are other signs of administrative apathy. Its building needs to be overhauled. Staff quarters too are in disrepair. “A full renovation of the PHC will cost Rs 3 crore,” said the medical worker. “This has been shot down each year saying the expenditure is too high.”

The administration, however, has spent Rs 819.22 crore on MV Atal and MV Ashoka.

Campbell Bay is not an exception. In Hut Bay (Little Andaman) too, there is no doctor for the ultrasound machine, forcing patients to travel to Port Blair for scans. Earlier this month, when chopper tickets weren’t available, an 82-year-old diabetic heart patient had to endure a 10-hour ship journey from Diglipur to Port Blair. In Car Nicobar, there is a dialysis unit but no technician. In Port Blair itself, the leading government hospital doesn’t have MRI facilities. “Patients have to go to a private hospital for scans,” a businessman in Port Blair told The News Minute.

It gets worse. “Earlier, specialists like ENTs used to go to the far islands like Car Nicobar,” said the businessman. “That has been discontinued as well.”

The News Minute wrote to LG Joshi and CS Kumar asking them to explain these decisions. No answer had been received by the time this report was published.

On the whole, NFHS-5 data suggests infant and under 5 mortality numbers, an indicator for community health, have risen between 2015-16 and 2019-20 (IMR from 9.8 to 20.6; child mortality from 13 t0 24.5).

This, however, is just one instance. Elsewhere in the islands too, hideous mis-governance shows up.

Marginalisation threatens indigenous communities

The map makes for sombre reading.

A pre-tsunami sketch of Great Nicobar, it shows where close to fifty villages of the tribal community of the Nicobarese, stood on the island. As books like Simron Jit Singh’s In The Sea Of Influence describe, these communities were self-sufficient with distinctive cosmologies and community structures.

“The plantations were the commons,” said one tribal elder. “People used to take turns to make copra.”

Then came the tsunami.

The worst impacts were felt in the Nicobars. Trinkat broke into four pieces. Waves crossed Katchal and rejoined the sea on the other side. In Car Nicobar, as many as 2,000 people died. Such was the quake that the archipelago itself tilted. Great Nicobar dipped, pulling the lighthouse at Indira Point into the sea, while North Andaman rose, pushing coral reefs off Diglipur above the waterline.

What happened thereafter is well-known. Six of the 12 inhabited islands in the Nicobars were entirely evacuated. “Nearly 29,000 survivors, both Nicobarese (roughly 20,000) and non-Nicobarese, were relocated to 118 relief camps across Car Nicobar, Nancowry, Kamorta, Katchal, Teressa, and Great Nicobar,” wrote Frontline in 2024.“By mid-2005, temporary tin shelters were erected for the displaced Nicobarese, where they received basic amenities, rations, relief supplies, and financial assistance.”

On Great Nicobar, most of these villages ceased to exist. The number of families, estimated at 400 by a tribal elder before the tsunami, fell below 100. Survivors were moved to three settlements — Afra Bay in the north; Rajiv Nagar in Campbell Bay; and New Chingenh near Jogindernagar.

What happened thereafter is staggering. Even 20 years after the tsunami, these survivors have not been allowed to return to their villages. The Nicobarese wanted to. “That is a good place for us,” said a tribal elder in Campbell Bay. “We can have our plantations of supari (arecanut) and nariyal (coconut). There is also crab export that we can get into. We have been saying this to the administration but there is no response.” The administration’s defense pivots around expenditure, he said.

“They say: It’s far. There is no road. It is not easy to provide medical and schools in the villages. Which is why we shifted you here. If there is a tsunami again, how will we take care of you’.”

These are odd responses. Take Chingenh. This village of 100-150 houses, located just to the east of Galathea Bay, had a primary and middle school before the tsunami. “It was a big basti (settlement),” said a local. “Buses ran till 6 in the evening. If these were possible then, why not now?” Similarly, if the administration is worried about another destructive tsunami, why is it building the transhipment port at Galathea?

Even as the administration barred the Nicobarese from moving back, it did not help these communities recover from the tsunami. At both Chingenh and Rajiv Nagar, locals asked for nearby land on which they could set up plantations. They didn’t get any. As a result, in both Rajiv Nagar and New Chingenh, survivors are working as daily rated mazdoors (DRMs) or contract labour. “They have been forced to move from a plantation economy to a finance economy,” said anthropologist Anstice Justin. “They used to grow arecanuts, coconuts, vegetables and edible roots in plantations and village gardens. Now they have been pushed into wage work.”

Coming with deep social and cultural losses, such shifts amount to ethnocide. Without plantations, the Nicobarese no longer have room or raw materials for their traditional functions. “A ceremony that used to take a week now gets done in a day. We do not have the samagri (materials),” said a tribal elder. This point is also made in a letter from the Tribal Council to the A&N administration. “Every activity (our customs and economic practices) we conduct through our traditional livelihoods are intricately connected to our erstwhile homes/villages that govern and “construct” our tribal identity,” says one letter written in 2022. “This important aspect of our right to self-determination and choices for livelihood is missing in our current dwellings and circumstances.”

In tandem, with shelters built for nuclear families, old joint family structures, as detailed by Singh in his book, have been decimated as well. “Families have all broken up,” said one elder in Rajiv Nagar. “Our children have not seen Nicobarese culture.”

Proximity to mainland settlers has been a variable here, he said. “In places like Afra Bay and Makachua to the north, tribals are doing a better job of persisting with our traditions.” Even there, however, there are problems. Two of their islands with plantations and spiritual significance — Menchal and Meroe — have been summarily turned into wildlife sanctuaries, without informing the tribal councils in time and despite the tribal council subsequently opposing the decision — and despite a lack of clarity if these islands are large enough to support the translocated species. Meroe, for instance, is just 1.29 sq kilometres in size.

The News Minute wrote to LG Joshi and CS Kumar asking them to explain these decisions. No answer had been received by the time this report was published.

****

On yet another front — that of the economy — the administration is dragging its feet.

Land conversion — which lets locals repurpose farmland for housing, or residential land for commercial uses — is one instance. “Land conversions used to be handled by local SDMs,” said the head of a business family in Port Blair on the condition of anonymity. “About 8-10 years ago, after allegations of corruption, the administration took over those powers saying it will create a new system.” Accordingly, in around 2020, a new committee, with the chief secretary amongst the members, was set up.

What happened next is instructive. One, the idea of the committee was bad in law. “The Andaman and Nicobar Land Revenue and Land Reforms Act and Rules says land conversions have to be approved by the Sub-Divisional Officer,” said the head of the business family. “The idea of the committee is unsupported by existing law.”

Groups like industry associations went to the High Court and then the Supreme Court and got orders in their favour. The administration, however, has neither returned to the old system nor held any meetings of the Committee. “In effect, there is no policy,” said the business family head. “This has stopped any growth. Firms like Westside and KFC, which want to set up outlets, are not finding clear land. IOC, which wants to set up petrol pumps, is not finding land either. Settlers cannot build a house on their own farmland. All the money which could come into the local economy because of construction is stuck.”

At the same time, however, the administration is converting government land for firms participating in its tourism bids. “Over the last 5 years, the administration has been trying to get investors for 4 and 5 star hotels,” said the business family head. “In the first set, there are four islands — Neil, Long, Avis, Ross and Smith. Thereafter, another 11 islands will be given out. This project, which was first under Niti Aayog, has now been taken over by ANIIDCO again.” For these, he said, the administration is converting government land and giving it on a platter to private companies.

Bid conditions, however, are such that local firms will struggle to participate in these tenders. “The financial eligibility is Rs 100-200 crore. Technical expertise is 5 years’ experience in running 5 star hotels. Given such terms, locals will not qualify.”

This pattern — of posting tenders too large for locals — extends beyond administrative centres to touch even villages. “In the past, panchayats had the power to issue tenders up to Rs 6 lakh,” a resident of Campbell Bay, the administrative centre of Great Nicobar, told The News Minute. Proposals for small civil works — like minor road repairs — went to the Gram Sabha. Once approved, assistant engineers would see the fund availability certificate and then approve the works. If funds were available, the work would be bidded out to local societies — each run by a group of 11 locals each. “This was another form of income for us,” said the villager. “Average annual incomes here are low. And so, when we take a project from the panchayat, we will be left with a profit of Rs 30,000-Rs 40,000. This sum would be shared within the society members.”

Take Campbell Bay. It has three panchayats — Campbell Bay, Laxminagar and Govind Nagar — and, within those, about 32 societies. With each panchayat issuing 3 or 4 such projects each year, that worked out to a local expenditure of Rs 45 lakh-Rs 60 lakh— and about Rs 9 lakh-Rs 12 lakh in retained earnings for the locals. “Chota mota kaam isse hota tha (local jobwork was done with these funds,” said an official in the Campbell Bay panchayat office.

This system has now been done away with. In 2024, the administration took away “cheque power”, said the official in the Campbell Bay panchayat office. “All tenders are online now. The government says this will stop corruption. Now, all tenders have to be over Rs 600,000 and they have to be tendered.”

With that, incomes from local construction are now flowing to government contractors — some of whom also have political links with the BJP. In Campbell Bay, for instance, both Sanjay Singh and ES Rajesh, the past and current pramukhs, belong to the BJP and are civil contractors.

In tandem, locals have found their lives disrupted in two ways. People earning from societies have been displaced. “We have 7 societies in Campbell Bay panchayat,” said the panchayat official. “In all, 77 families lived off this work.” The new system is also less responsive. “The advantage of the old system was that work would get done within 15-20 days,” a resident of Vijaynagar told this reporter. “In the new system, there is no guarantee. Chota mota kaam sab ruka huva hain (small jobwork is at a standstill).”

Letters asking the UT administration to rethink, said the panchayat official, have not received any response. The News Minute wrote to LG Joshi and CS Kumar asking them to explain these decisions. No answer had been received by the time this report was published.

****

These instances — shipping; healthcare; post-tsunami rehabilitation of the Nicobarese; and the denial of economic opportunities to locals —are just the tip of the proverbial iceberg. On a clutch of other fronts too, islanders — tribals and settlers alike — are struggling.

On Great Nicobar, the government’s claims in the parliament notwithstanding, both the Nicobarese and the Shompen will be affected by the proposed port project. As the government works on plans for the western coast as well, the Nicobarese are worried about their ancestral lands being lost forever.

As for the Shompen, the hunter-gatherer tribe lives in the island’s hinterland — with groups living across the island, from its top to Galathea Bay in the south. These groups in the south will be displaced by the project. “If they are pushed north, they will come into conflict with other tribespeople,” said a researcher who has worked in the islands. As human activity rises on the islands, interactions between the Shompen and outsiders will rise as well.

As the Onge and the Great Andamanese show, such interactions can be ethnocidal. When books like Madhusree Mukherjee’s Land Of The Naked People, the Jarawas were still trying to balance their traditional lives and the world outside. Over the last ten years, however, that tightrope walk has faltered. “AAJVS is giving alcohol to the jarawas,” said Justin. “If you look at their teeth, they are red from betelnut. We are now seeing instances of cancer. They have a potbelly.” That is because, he said, the AAJVS is giving them edible oil and rice in return for crab as a currency.” The Jarawas, he said, are heading the Great Andamanese way.

As these anecdotes over shipping, healthcare and land conversion show, settlers are struggling as well. On Great Nicobar, as Campbell Bay gets subsumed into the project, most settlers will lose their land. As with the Nicobarese, the government doesn’t want to give alternative land. “The government says it doesn’t have enough land and so people who lose 11 acres might get just 1 acre,” said a resident of Vijay Nagar, one of the villages affected by the proposed airport. “My husband’s family came here when there was nothing,” she said. “After the tsunami, we went back 20 years. Just as we recovered, this airport has come. We spent all this time on the land and now they want to take it back.”

The project, however, is getting 130 square kilometres of the island.

Elsewhere in the archipelago, the water crisis continues to fester. The administrative decision to use biometric verification at ration shops in these remote islands is making it hard for locals to claim rations. Inter-island movement is in shambles. Flight tickets are hard to come by — and the ship schedule, given lack of ships, comes with large gaps. “Anyone travelling from Great Nicobar to Car Nicobar will have to wait as long as a week at Nancowry before the next ship comes,” said a government employee stationed at Campbell Bay. “People sail first to Port Blair and then take a ship back!”

This reporter wrote to the LG and the Chief Secretary asking them to comment. This article will be updated when they respond.

There are many other fronts in which administration has moved with extraordinary speed.

The proposed port-city complex at Great Nicobar is one instance. Public hearings have been rushed through. Two wildlife sanctuaries — one for turtles and the other for the Nicobar Megapode — have even been shifted from the project site at Galathea Bay to the island’s western coast. As a forest officer who has served in Campbell Bay asked: “Can protected areas be shifted? If animals don’t go there, how did we declare a place as a wildlife sanctuary?”

More recently, even as wildlife researchers at WII and Sacon seek two years to gauge the project’s impact on the government’s (randomly compiled) list of locally endemic species like the Nicobar Macaques, Megapodes and Saltwater crocodiles that will be affected by the project, the Andaman and Nicobar Industrial Development Corporation (ANIIDCO), which is implementing the project under the supervision of the home ministry, has nonetheless invited expressions of interest for logging.

“We are not being told when logging will start,” said a researcher working on the project. “We are afraid the administration will tell us, in some months or maybe a year, that ‘Logging is starting. Capture what you can. Save what you can.”

New colonialism?

In effect, the archipelago is being colonised all over again.

During colonialism and India’s heady post-independence decades, the tribals were pushed aside by the settlers. This process is playing out again now, with a clutch of bureaucrats and firms from the mainland marginalising not just the locals but also provincial capitalists.

Great Nicobar is not the only project coming up on the islands. There are also plans to set up a deepwater port in Diglipur — at least one firm, called Meinhardt Shipping from Singapore, has already made a presentation to the UT administration. There is also talk of creating a huge tourism centre at Hut Bay, not to mention plans to set up resorts on eleven islands. And then, there is Great Nicobar itself.

Little of this, however, has been discussed with the locals. “The administration should at least talk to MPs and elected representatives,” said Tejasva Rao, organising secretary of the Congress in Port Blair. “At this time, no one is being taken into consideration — not the tribals, not the business community, not elected leaders, not the locals.”

This unaccountability extends beyond construction projects to bureaucratic privilege.

While at Port Blair, I heard about an IAS officers’ two-day trip — with spouses — to Barren Island for which MV Sindhu had been pulled out of its regular sailing schedule. The ship works through the week. Leaving Port Blair on Tuesday morning, it reaches Campbell Bay on Wednesday afternoon or evening. Heading back the very next morning, it reaches Port Blair on Friday morning. On Saturday, it heads to Little Andaman, returning to Blair only on Monday. Despite this schedule and locals’ reliance on the ship, at least two times last year, government officials commandeered the ship for weekend trips to Barren Island. “The ship left Port Blair on Saturday and returned on Sunday,” said the business family head. “This happened last year, under the previous chief secretary. On both weekends, Hut Bay didn’t have a ship service.”

This reporter wrote to the LG and the Chief Secretary asking them to comment. This article will be updated when they respond.

I heard too about an Ahmedabad-based firm called Dineshchandra R. Agrawal Infracon which has bagged the tender to re-tarmac the airstrip at Car Nicobar.

To create an additional landing space for its construction material, the firm has dumped sand inside the harbour to create a makeshift barge landing jetty. This is resulting in the harbour silting up — with ships unable to dock as before. This reporter has seen letters written by the tribal council in 2022 — and again in 2023 — to the administration asking for relief.

When I met them in 2025, the problem remained unaddressed.

In tandem, the administration is getting more intolerant towards criticism. As this reporter has written elsewhere, it’s trying to stop outsiders — even tourists — from visiting Campbell Bay even though the administrative centre of Great Nicobar is revenue land and, ergo, open to all Indians. A reporting team from The News Minute that reached the island—making the 30-hour journey by ship—was followed and questioned by local police and Intelligence Bureau officers.

This intolerance extends to locals as well. The administration is quick to issue prohibitory orders to curb local protests.

“We cannot speak,” said the resident of Vijay Nagar. “If we do, local politicians will make it hard for us.” Government employees too have been disciplined — through instruments like postings to the far islands. “There is no media here and so, they behave like this,” said a mid-level bureaucrat who had been transferred to Campbell Bay, compelling him to leave his aged father alone in Port Blair. “If they knew they could get filmed or their deeds could go public in some other way, they would act differently,” he said.

The outcome is striking. On one hand, the administration materially shapes locals’ lives — their access to traditional lands, medical care, travel; and determines where they stay and how they earn. At the same time, it acts with extraordinary unaccountability, circumscribing locals’ lives as well as announcing grandiose plans. Earlier this year, for instance, LG Joshi said a global medical hub will be developed on Little Andaman. This plan, however, sidesteps questions about the administration’s current track record on healthcare delivery or why anyone unwell will fly to an island in the middle of the Bay of Bengal.

Given pervasive underdevelopment, however, locals end up pinning hopes on such announcements which, like the transhipment port, might eventually produce only EPC and logging booms.

In all, anger against the administration is rising. “There is more anger now than there was five years ago,” said the Directorate of Shipping official, on the condition of anonymity.

M Rajshekhar is an independent reporter who writes on ecology, energy, development and the fraying social contract between Indians and the political parties that purport to represent them. He is also the author of Despite The State: Why India Lets Its People Down and How They Cope, published by Westland Books in 2021.