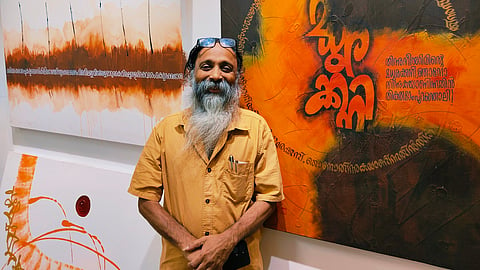

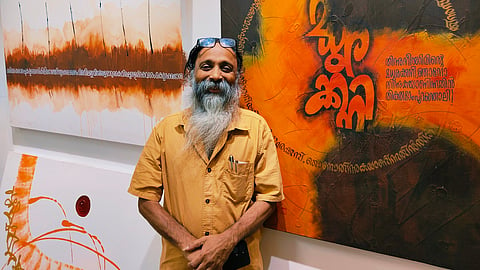

Although it looks fitting, the traditionally built house at the turn of the lane is not the address Narayana Bhattathiri has given. One might imagine that the decorative roofing is just the kind an artist might put on top of his home. But no, Bhattathiri has tucked his house a little further away into a corner you might miss if you weren’t looking for it. Like his art, his abode too is unexpected. You barely notice the name of his gallery hung on top of the little gate leading to it – ‘Ka Cha Ta Tha Pa’.

We are in a central spot of Thiruvananthapuram city, in Vazhuthacaud – a location that should ideally attract new interest and students to the art of calligraphy that Bhattathiri has been relentlessly propagating. After landing in the field accidentally in his university days, he has remained steadfastly attached to calligraphy, learning new tricks and trades even at later stages, practising it without a day’s break and trying his best to bring more people into it.

But for reasons unknown, few in Kerala have taken to the art. Bhattathiri’s remains the one name that most people in the state associate with the art, and earlier in November, he quietly garnered global recognition – appointment as honorary director of the World Calligraphy Association.

“In the dictionary, calligraphy is defined as the art of beautiful writing. Before printing was invented, the only way to spread the written word was to copy it in writing. It had to be written beautifully so that everyone could read it. That is how the art of calligraphy came to exist,” Bhattathiri offers a little history.

But when printing was invented, the purpose of calligraphy as a tool to spread the word was lost. It evolved into an independent work of art.

Bhattathiri can’t stress enough that the art has nothing to do with what is written. The letters can be anything – “and indeed many people simply use a, b, c, d” – he says. “It is the beauty of the letters that counts.”

Most of the visitors to his gallery are in fact people who do not know Malayalam and yet never ask him questions on what every piece of writing means. Across the glazing white gallery, spread over uneven wooden flooring, are Bhattathiri’s lettered canvases. The Malayalam alphabet on them curves or slants or goes on a straight line until they stop looking like letters and magically turn into pretty pieces of art.

Bhattathiri developed a habit of reciting the poems of Vyloppilly or Kumaranasan or Chullikad while he woke up at 3 in the morning and began his work. The verses may find their way onto his paper but he immediately brushes off any literary connection – the words don’t matter, he repeats, it is the art.

As a child growing up in Pandalam, Bhattathiri had not known about the art of calligraphy but he was known for his beautiful handwriting at school and was picked up to make posters. At the Fine Arts College in Thiruvananthapuram where he came to do his degree, a senior called S Rajendran took him under his wing and the two began to do poster designing. “I was staying away from home and needed to fund my studies, so I would use the income that came from poster designing,” Bhattathiri says.

Rajendran also took him along to Kalakaumudi, a popular Malayalam magazine, where they found new jobs. Bhattathiri was curiously given the job title of calligrapher – the first time such a job was created in Kerala, he says. Sadly, after he left, the job title faded away, and no one took his place. When he joined another magazine called Malayalam, he became a calligrapher and designer.

“Mostly, the designers or else the illustrators do the calligraphy – of writing headlines artistically. Before I joined Kalakaumudi it was the veteran artist Namboothiri who did the illustrations as well as the calligraphy. Then the job came to me, and in 18 years I have worked on more than one lakh headlines,” Bhattathiri says.

He designed the title for MT’s Randamoozham and Mukundan’s Daivathinte Vikurthikal and many others, but the calligraphy largely remained unnoticed, until the titles were taken out and put on a canvas on their own.

In 2016, Bhattathiri’s friend Sundar, a writer, urged him to hold an exhibition of his best works. It was, the artist says, a herculean task to zero in on 150 artworks from the tens of thousands. But that exhibition, held in Thiruvananthapuram, opened many new doors for Bhattathiri.

“No one had taken notice of my headlines when it came as part of other text in the magazine. But showcased independently as separate works of art, they drew attention,” he says.

On Sundar’s suggestion, Bhattathiri began practising calligraphy independently, not merely as headlines for books or stories anymore. He posted his work on social media regularly, and a Bombay-based calligrapher called Sarang Kulkarni enquired if he would like to join a national camp in Pune. Bhattathiri, of course, did.

It was a one-month camp for designing a calendar, with 12 calligraphers on board – one person in charge of every month. Bhattathiri became acquainted with calligraphers outside Kerala and realised it was a much more recognised field outside south India.

“I also realised it has evolved into new forms, that one need not just put it out as titles the way I had done before. It can take any shape and size and become entirely independent works of art like paintings.”

That’s when Bhattathiri’s letters began to twist and turn and go any which way they wanted on a canvas, with a mind of their own. In 2017, he got another call, this time from the Indian Embassy in South Korea, to ask if he’d like to exhibit his work at the Jikji Festival. “He told me no one from India has taken part in that festival before.”

They even sent him the paper he could work on when he said the paper they asked for was not available in Kerala. In that first year at Jikji, Bhattathiri won the excellence award. The director of the event showed him a 100 rupee note with 15 different Indian languages and asked if there was no calligraphy in all of those. The next year, Bhattathiri called his contacts from the Pune camp, collected calligraphy works in 16 languages, and made another trip to Korea. He won again.

He began making the trip almost annually. When he won the excellence award thrice, they made him a jury member. But Bhattathiri kept taking more and more works every time, until last year he had 172 artworks from a number of artists and a whole floor was dedicated just for India. No surprise that they have now appointed him the honorary director of the World Calligraphy Association.

Back home in Kerala, he began to hold national workshops bringing calligraphers from different parts of the country. Finding a bigger response in Kochi than in Thiruvananthapuram, he conducted an international calligraphy festival in the port city.

Despite his best efforts to promote calligraphy among younger generations, it is yet to catch on. Bhattathiri hopes that the workshops he organises at Ka Cha Ta Tha Pa – anyone with or without a background in art can join – along with his national camps and international festivals will eventually make a difference.