This article contains spoilers for the film ‘Lokah Chapter One: Chandra’.

It is late at night. A lone man walks along a narrow village road, the fields of paddy on either side shimmering under the moonlit night. The air is heavy with the sweet smell of the ezhilam pala flower, and the distant cawing of crows punctuates the quiet. On one side, the dark line of the woods looms. From its edge, a figure steps out from the shadows — a woman, alone, draped in a white sari, her long black hair glinting, her eyes wide and luminous. She asks softly if he will walk her home. Enchanted, he agrees.

Along the path, she offers him betel leaves, her hand brushing his. When she asks if he has slaked lime to go with it, he recognises the coded invitation. Desire clouds his judgment, and he follows, heart pounding.

But then, as they reach a clearing, her form unravels. Eyes blaze red, fangs appear, and her hands sharpen into claws. By dawn, only remnants remain — betel-stained teeth, torn hair, shredded nails, proof of the yakshi’s vengeance.

Stories of the yakshi, Kerala’s vengeful female spirit, have been passed down for generations. The lesson is always the same. The yakshi may appear beautiful, but beneath that beauty lies absolute power and deadly wrath. In many versions, her fury is so relentless that only a tantric can contain her, driving an iron nail into a Kanjiram tree to hold her spirit in place.

Over the years, popular culture magnified this image, often dwelling on her beauty as much as her brutality. On screen, she was sexualised and sensationalised, shaping her into an enduring fantasy of the femme fatale.

Yet, legends do not remain static.

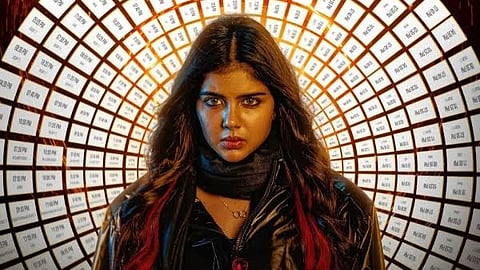

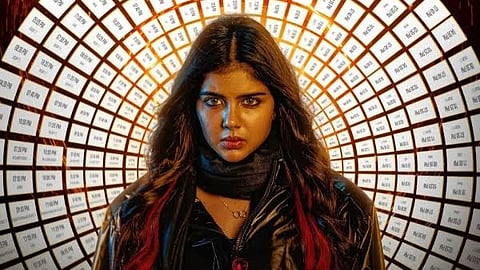

In the 2025 Malayalam superhero film Lokah Chapter One: Chandra, the yakshi steps out of the shadows of myth into the contemporary city, and she is nothing like the seductress who haunted lonely roads and terrorised men. Here, the yakshi of Kerala’s folklore — arguably the most infamous of them all, Kalliyankattu Neeli — is reimagined. Gone are the white saris, the pitch black hair, the coded invitations. Instead, Neeli, or Chandra (Kalyani Priyadarshan) as she is called in the film, wears cropped tops, jackets, and jeans, her hair streaked with blazing red.

Where once the stories of Kalliyankattu Neeli were tales of male desire and punishment, Lokah, directed by Dominic Arun and co-written by Santhy Balachandran, recasts her as a saviour rather than a seductress.

Of course, she still directs her wrath at men who trespass, but there is no lure in her gaze, no promise of intimacy. Her power is not measured in the fear she incites, but in the lives she shields.

The lore of Neeli

While the story of Kalliyankattu Neeli may have circulated orally for centuries, it is Kottarathil Sankunni’s Aithihyamala (Garland of Legends), published in the early 20th century, that cemented her place in Kerala’s imagination. The eight-volume compendium gathered more than a hundred legends of yakshis, brahmarakshasses, maadans, maruthas, odiyans, witches, saints, and nobles, and in doing so, canonised which tales would define Kerala’s folklore.

As per the Aithihyamala, Neeli was born as Alli, the daughter of a devadasi. Bound to the temple from childhood and barred from marriage with mortal men, Alli’s life was defined by caste and ritual. That was until her beauty attracted Nampi, a Brahmin priest, whose betrayal and murder of her became the origin of her transformation into the yakshi. The book has since been a touchstone for retellings, from kathaprasangams and temple recitals to television serials and films.

Here, Neeli’s so-called monstrosity is inseparable from the caste order of her time. As the devadasi’s daughter, her desire and defiance of the caste boundaries set for her, which she broke by choosing to live with Nampi, became grounds for her brutal punishment. The outlines of her tale mirror countless other yakshi stories — a woman betrayed by a man she loved, killed or abandoned, transformed into a monster who then becomes a cautionary tale. Her rage is hardly a mystery, as it grows directly from betrayal and violence. But the way these stories are told transforms this rage into something excessive and monstrous.

The yakshi, here, represents the erotic excess men long for, but also the punishment for giving in to that desire. Her very presence carries a warning — that women who are too ‘beautiful’, too desiring, or too defiant will turn monstrous. The horror, shaped by patriarchal and dominant-caste anxieties, lies not in male betrayal but in female vengeance.

In Lokah, however, Neeli embodies much more than this horror. The film acknowledges Aithihyamala, but instead of simply reproducing its account, the film treats it as one more layer in Neeli’s long afterlife — a story to be contested, not merely inherited.

Where Aithihyamala locked her in the mould of the seductress-turned-monster, Lokah reopens the myth to imagine what else she could be.

Her power, in the film, is physical and deliberate. The yakshi who once enticed and consumed men now acts decisively to protect the vulnerable. Her clothes signal her as a figure of action, not ornamentation. The film, essentially, allows the yakshi to reclaim space for herself, not as an object of terror or fascination, but as an agent of her own will.

Caste still anchors the story, but differently. This Neeli is a tribal girl, marginalised and forbidden from the spaces the king inhabits. When she and her friends enter his forest temple out of curiosity and accidentally carry away a trinket, it is not desire but survival and inquisitiveness that brings the wrath of authority upon them. The king sets their temple ablaze, massacres the community, and leaves Neeli and her family cornered. In the abandoned cave where she escapes, she gains strength and immortality through a seemingly supernatural encounter with bats. Her family is slaughtered, and the girl who once ran from danger now bites back, forging the mythic Neeli through trauma, anger, and the quest for justice.

The continuity with the old legend is clear. In both versions, Neeli’s power emerges from the violent enforcement of social hierarchies.

Where the devadasi’s daughter was punished for transgressing caste and gender boundaries, the tribal Neeli suffers at the hands of a king whose violence enforces exclusion. Both narratives frame her wrath as a response to structural injustice, whether rooted in patriarchal caste codes or feudal oppression.

Neeli and Kathanar

The role of Kadamattathu Kathanar, the legendary occultist priest, is central to Neeli’s story in the Aithihymala. As the legend goes, he is the authority who finally restrains the yakshi, reinforcing male control over female power. Kathanar here is not just a character, but the moral and ritual pivot around which Neeli’s legend revolves.

It’s worth noting that Kathanar may not always have been part of Neeli’s story. In some versions, for example, Alli’s murderous husband dies shortly after being bitten by a snake. She and her brother are then reincarnated as children of a Chola king, only for it to be revealed later that they are malevolent spirits, who are out and about at night slaughtering the villagers’ cattle. The villagers pursue the siblings and cut down the tree her brother has taken refuge in, killing him. Neeli then takes vengeance on the villagers, as well as her reincarnated husband, before eventually finding peace and transforming into a benevolent deity.

Nevertheless, the dynamic between Neeli and Kathanar has strongly influenced popular culture to the extent that Neeli is almost always mentioned alongside the priest. In the Asianet television serial Kadamattathu Kathanar, for example, Sukanya’s Neeli is the series’ first major antagonist, and her conflict with Kathanar drives the narrative. She is ultimately overcome twice by the priest, underscoring the familiar tension between female power and male authority.

Earlier cinematic references — the 1979 film Kalliyankattu Neeli (Jayabharathi as Neeli opposite Madhu) and the 1985 Kadamattathachan — mention her confrontation with Kathanar, cementing the idea that his presence is central to her story. Though not confirmed, Neeli’s presence is also expected in Jayasurya’s upcoming Kathanar: The Wild Sorcerer, which seeks to tell the priest’s story.

Lokah, however, reconfigures this relationship. Here, Kathanar is no longer the authority who restrains her. He is a collaborator, a “friend” who works alongside Neeli, while the narrative centres on her choices, her agency, and her power. Neeli, meanwhile, is the protagonist of her own story, and the moral and dramatic weight shifts from male control to female autonomy.

Yakshi in popular culture

Across decades of Malayalam cinema, the yakshi has often been sexualised as a femme fatale — a beautiful, dangerous woman whose allure can be fatal. These portrayals were often shaped by what critics call the Madonna-whore complex. She was either the object of men’s desire, presented through lingering shots and seductive costuming, or the terrifying punishment for succumbing to that desire.

In films of the 1970s and 80s, including Kalliyankattu Neeli and Kadamattathachan, the yakshi retained this image. Sree Krishna Parunthu (1984), for instance, follows Mohanlal as a rogue-turned-tantric whose celibacy is tested by seductive spirits. Though not strictly a yakshi film, it features figures like the bloodthirsty ‘vada yakshi’ and the tutelary ‘kudumba yakshi,’ weaving erotic temptation into a tale of power and moral decay. Here again, the supernatural woman is cast as the test and downfall of male spiritual authority.

Elements of this ‘lure’ can be seen across Kerala’s most popular horror films, from Aakasha Ganga (1999) to Indriyam (2000), where the yakshi’s power is intertwined with her sexuality. In Rajasenan’s Meghasandesham, she appears in vibrant sarees, her identity bound to her longing for a man. Vinayan’s Yakshiyum Njanum (2010) pushed this further, foregrounding low-cut blouses, exposed navels, and cleavage, presenting the yakshi as a hypersexualised figure.

Even recent films like Bramayugam (2024), which excels in many aspects of the horror genre from atmosphere to craft and performances, still falter when it comes to the yakshi. The film casts her merely as a bloodthirsty sexual being, a figure shaped more by male desire and fear than by her own history, grief, or complexity.

But not all portrayals in Malayalam cinema reinforce stereotypes. Malayattoor Ramakrishnan’s Yakshi (1967) and KS Sethumadhavan’s 1968 film adaptation turn the genre into a psychological thriller, probing male paranoia as the real horror. Shalini Ushadevi’s Akam (2011), a contemporary reimagining of the same story, pushes this further, exploring how men demonise women’s desires, rewriting the myth as an internal — rather than supernatural — menace.

Another counterpoint emerges in Vaikom Muhammad Basheer’s Bhargavi Nilayam (based on his story Neelavelicham), where the female spirit is not a seductive predator but a tragic figure with depth, one who evokes sympathy rather than fear.

But taken together, these films show how the yakshi’s cinematic afterlife has been dominated by the male fantasy. Against this history, Lokah’s shedding of this gaze, especially at the hands of a woman writer, is striking. Where earlier films froze her between the poles of Madonna and whore, Lokah recasts her as an agent of action, no longer bound to be either temptation or punishment.

There is no doubt that the film borrows significantly from Western storytelling tropes. Neeli’s transformation in the cave (bitten by bats and gaining powers) clearly echoes Western vampire myths, and her abilities are explained through a virus that only certain bodies can adapt to — a distinctly modern, science-fiction approach.

The film even includes moments that feel straight out of a superhero or vampire film, such as when Chandra pushes Sunny (Naslen) out of the path of a speeding car and vanishes. The scene is instantly familiar to anyone who has seen a certain type of modern fantasy.

However, while these borrowings make the film accessible to global audiences, they also highlight a missed opportunity. Lokah could have trusted its own cultural imagination more boldly. Kerala’s myths, forests, and temples are rich enough to craft a story that feels epic and wholly original without leaning on Western tropes. Neeli’s power, her moral clarity, and her haunted past remain inseparable from the space that made her.

Today, near Parvathipuram, roughly five kilometres from Nagarcoil, a temple dedicated to Kalliyankattu Neeli stands at the site where she was said to have been killed. Open once a week for worship, the temple is surrounded by remnants of the forest and the weight of Neeli’s legend. Stories abound of her ensnaring hundreds of men, feeding on their blood, and roaming relentlessly until subdued by Kathanar.

The temple does more than just preserve that myth. It anchors it in geography and history, reminding us that Neeli was never just a story of seduction or terror — she was a woman betrayed, a spirit wronged, and a force that claimed her space in the world.

Views expressed are the author’s own.