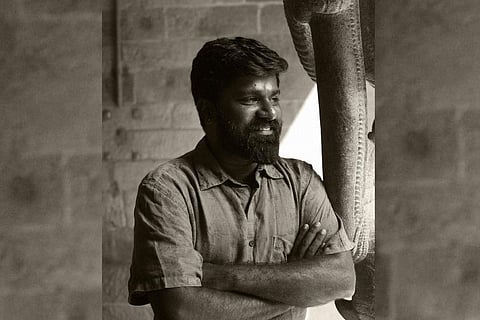

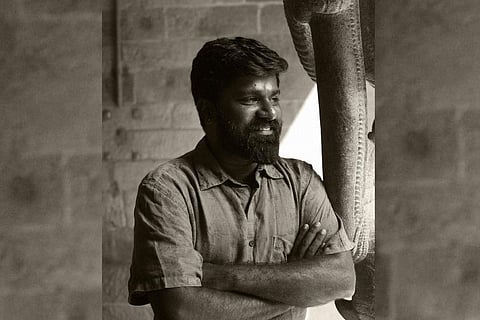

“I feel like a fish,” Madurai-based photographer Jaisingh Nageswaran told us at some point in the conversation. We were talking about his life at his parents’ house in Vadipatti, where Jaisingh has now been living for over a year — the longest he’s been since moving out to live on his own in his early 20s. Over the past two decades, Jaisingh has worked in Bollywood while pursuing his independent documentary photography projects. Sometime in early 2020, he moved back home due to an ailment. Then the pandemic began.

Jaisingh Nageswaran is among the two Indian photographers who have been selected by the USA-based Magnum Foundation, a nonprofit organisation for documentary photography. He is among this year’s 11 selected Photography and Social Justice Fellows and is the first photographer from Tamil Nadu to be selected. The simile about the fish is also the title of the work that won him the fellowship.

“It was around the 10th or 12th day of the lockdown that I began feeling claustrophobic, restless and shut-in. But this feeling was not entirely new to me,” Jaisingh says. It was a sense of déjà vu for the 43-year-old, for whom social distancing and social exclusion were ever present in life and the cause for intergenerational trauma. “We are not new to social distancing. Isolation, social distancing may be new for others but for me, it is something very familiar. We’ve been told not to enter certain streets and homes… This is how we’ve been forced to live because we are Dalits,” Jaisingh adds and goes to explain an incident that would turn out to be a moment of epiphany for him. “So one day during the lockdown, when my father was moving the fish tank in the house, I had a sudden revelation. I am the fish, and my world is the fish tank. I feel like a fish," he says.

Jaisingh tugged hard at this string and began weaving a tapestry with it. In his latest work, ‘I feel like a fish’, Jaisingh documents his own life, his house, his family and consequentially the Dalit experience in modern India. “I do feel the need for documenting my parents and I regret not having done it earlier. We don't have proper archives of Dalit lives in India. In Nepal they released a photo archive of Dalit lives (Dalit: A Quest for Dignity) and this too was taken majorly by photographers who aren’t Dalit themselves. In Tamil Nadu, we have intellectuals like C Iyothee Thass but how good are our archives? At home, we don’t have a proper archive of the school that my grandmother founded. I look at my work as important documentation of my family,” Jaisingh explains.

“What is my place in India’s history of photography? I turned the camera towards myself; I started at home,” he adds.

Jaisingh’s photos are documentation of daily life in his home. His father getting a shave, his sisters playing, his nephews watching television… There’s also the eponymous fish in the tank.

For Jaisingh to have arrived at this point, it was a journey wrought with questions on identity. “Growing up, I never felt comfortable talking about my family. I’ve always wanted to live as far away as I could from home,” Jaisingh confides. This feeling was sown by several bitter experiences during his growing-up years. “I’ve seen friends turn indifferent when they learn about my caste. And even to this day, the treatment is the same. Quite recently, a well-known documentary fillmmaker introduced me as a Dalit photographer to a gathering. Do you know how that made me feel? I felt the same anger and embarrassment and disgust that I felt years ago when a friend’s mother who was serving a group of us lunch replaced my plate alone with a plantain leaf. I’d like to be seen as a human, I did not ask to be born a Dalit. Tagging me as a Dalit photographer is social injustice. Would he have introduced anyone as a ‘Nadar’ photographer or a ‘Baniya’ photographer?” he asks.

Over time, Jaisingh had to rise above the anger to see clearly for himself of all that lay in front of him. For this, he says, an interaction with photographer Dayanita Singh was a turning point. “She told me not to shy away from who I am. I took this very personally. If I wanted to change anything, I had to change it myself. I realised that I had not told my own positive story, of Ponnuthai’s [his grandmother] story to this world. Maybe I've become a photographer for this very reason.”

As part of the fellowship, Jaisingh will also explore everyday caste atrocities and caste-based discrimination in his region. The fellowship will give him access to seminars and lectures by international photographers, in addition to lifetime mentorship and support from the community. Jaisingh, at present, documents using his iPhone. He’s also got parallel projects such as ‘Down By The River / Mullai Periyar’, that is a splash of life along the banks of the Mullai Periyar, and the long-term photo documentary ‘THE LODGE’, on the lives of trans women in Tamil Nadu. Each of these, Jaisingh prefers to work on using different mediums, from film camera to polaroids. This he compares with an artist using different canvases.

While he admits that the documentary form may still be under-explored in India, Jaisingh believes in the power of telling personal stories. “Coming back home, spending time with my nephews Ezhil and Kirubakaran, has given me a new outlook. All of my childhood memories — of my grandmother teaching me numbers under the shade of trees in the fields, of my grandfather buying cows, walking them home overnight and selling their meat on Sundays — have all contributed towards forming my current aesthetics. By spending time with my nephews, taking them to the river, walking to the foothills in the evenings, playing with goats, I am able to rediscover the child in me, break my own ego and look things differently,” he says.