For many who grew up in Chennai, the Madras Crocodile Bank Trust (MCBT) and the adjoining Irula Snake Catchers Industrial Cooperative Society is a familiar place. It’s where one can go to watch how snake venom is extracted to produce antivenom and know who the Big Four are. If you are so inclined, you can even sign up for a snake walk led by the well-known tracker Kaali who works for the co-op and members of the MCBT team.

What’s a snake walk? Who are the Big Four, you ask? For the uninitiated, the Big Four, as much as they sound like mob bosses in a Hollywood gangster flick, are the four most common venomous snakes in India. Namely, the Spectacled Cobra, Saw-Scaled Viper, Russell's Viper and the Common Krait.

Antivenom used in India is manufactured from the venom extracted from all four of these snakes. The Irula co-operative employs part-time and full-time members of the Irular community to track, capture and extract venom from the Big Four which is sent to labs that produce the antivenom.

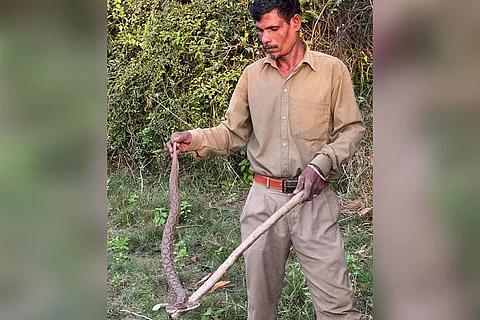

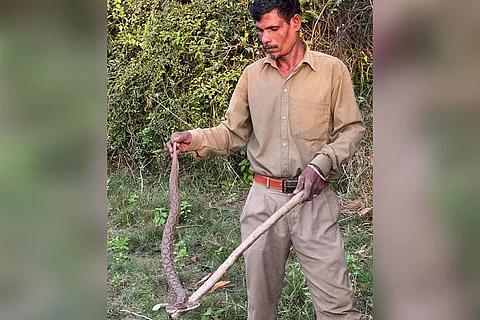

Kaali is a familiar figure for Chennai’s snake enthusiasts and those who attend the walks conducted by MCBT. The latest such walk was conducted on April 10. Just past dawn on select Sunday mornings, Kaali scours the scrublands opposite the MCBT grounds, tracks down irritable adult saw-scaled vipers, mistakeable to the layperson for baby snakes because of their diminutive size or shy nonvenomous vine snakes or any of the serpents native to the area. In tow are a motley group of snake enthusiasts, some still rubbing the sleep from their eyes, listening in fascination as Kaali and MCBT members speak about each snake. Whether they are venomous or nonvenomous, their personalities, whether they lay eggs or birthed their young, what they eat, if they are nocturnal or not. The snakes caught on these walks are released after this short talk.

This Sunday’s walk begins with Kaali and his wife Alamelu tracking down a Russell's Viper. Understandably peeved at the sudden disturbance, the viper let off its trademark “pressure cooker” hiss: long exhalations through its nostrils that sounds remarkably similar to a pressure cooker going off.

Nestled away in the same little grove they find a Russell’s Viper as well as a Spectacled Cobra—called so because of the eyeglasses-like markings on the back of their heads (those interested must also look up the less common Monocled Cobra; you can guess how it got the name).

One of the last snakes tracked down during the walk is an adult non-venomous Bronzeback. A slender, feisty species, it puffs out its body when threatened. This tactic lets you see an underlayer of iridescent scales that glow a deep blue when they catch the light.

But how does Kaali or other Irular snake-catchers like him know how to find the snakes? Kaali says he understands from the faint tracks a snake leaves on the ground, what species is likely to have left the marks. “If the dew has settled on the inside of the tracks, obviously the snake went by before sunrise. So, it’s a nocturnal species,” he tells TNM. The addi (footsteps), that is the space left by each turn of the snake’s body gives him clues about its girth much like our own footsteps could give away our height.

The Saw-Scaled Viper, when annoyed at being disturbed, creates a dry, rustling sound by moving its body. When quiet, it’s an easy snake to miss for the untrained eye, with its brown colouration especially against a scrubland floor.

But Kaali knows exactly where to look, because each snake has preferred habitats even within the same geographical area. “The Saw-Scaled Viper will likely be in the bushes. Particularly, the young because they need to protect themselves from predators including other snakes. Kraits often consume smaller snakes, among other animals. I have even seen one Krait eating another, but that is likely only in extreme situations when there’s a scarcity of food. Usually, they don’t eat their own,” says Kaali.

“A shed snake skin can help locate the snake, apart from giving away what species of snake left the skin behind,” he says. “From the scent on the skin, it’s possible to tell how old the skin is, and how far it’s likely to have gone. So, it gives a search radius.” On Sunday’s walk, one of the participants spots some skin along the path. “A Common Krait,” Kaali says easily. “You can tell from the hexagonal scales running down the centre,” adds Steffi John, one of the MCBT staff coordinating the walk.

Note the hexaganol scales at the top, identifying the skin as belonging to a Common Krait. Image courtesy: Steffi John, MCBT

Once Kaali tracks down the snake, examining it will tell him whether the reptile is male or female. This comes in particularly useful when tracking snakes to catch for venom extraction back at the centre. “If I catch a spectacled cobra that is pregnant, I let it go. Carrying it away from its habitat, the shock and alarm of being caught could lead to a miscarriage. If one is not conscious of these things, future numbers of the species will suffer, as will the livelihoods of those tied to these creatures,” he warns. “Similarly, I do not catch snakes that look malnourished. Again, taking it away would endanger its life and the venom extracted from it when not fully healthy, would be an inadequate amount,” Kaali adds.

Kaali who is now in his forties, has been tracking and catching snakes since his childhood. “I learnt from my father, Chockalingam, who was instrumental in setting up the Snake Park along with famous herpetologist Romulus Whitaker. I decided to learn because I did not want this knowledge to die away.” Having started at the age of seven, Kaali says. “I only caught nonvenomous snakes first. Then I went on to cobras, then saw-scaled vipers, then Russell vipers and finally, [Common] kraits. I still remember when I caught my first cobra,” Kaali laughs, “I was so scared, it looked so large and angry with its hood.”

If you haven’t been to one of the Sunday morning displays of venom extraction at the Co-op, it can be a bit of a shock. A concrete construction sunk deep in the ground is where the work is done for public view. The extraction is done by members of the Irular community who work at the Co-op. Earthen pots line this pit of sorts, inside which several of the Big Four are resting. Three or four specimens of each species are pulled out at a time with a long hook onto a slab, decorated with pictures of Pillaiyaar, Jesus and Mecca with offerings of a few rupees. A small blackboard keeps track of the number of each species currently held at the centre.

About five men are in this pit at the same time. The device to extract the venom is quite simple: A plastic cup on a stand is covered over with a rubber sheet tightly. The snake is forced to bite the rubber, releasing venom into the cup below. The entire setup seems to offer little protection to the men.

“We each focus on one thing,” Kaali says. “One person is explaining about the snake to viewers, one does the extraction. Two or three others only monitor the snakes. They move them away, if they get too close. People who come to watch the extraction, expect a spectacle. If we have just one of each of the Big Four out, they are disappointed and they complain. So we have to do this.”

This is not the only problem Kaali and other Irular trackers and extractors like him have to deal with. The payment for the tracking and catching for venom extraction at the Co-op is set by the management in consultation with the Forest Department. There is a rate for each of the Big Four. A spectacled cobra pays Rs 2,300, for example. Despite kraits proving to be elusive, dangerous and more venomous than the other three, it pays only Rs 800. So far, talks with the management have proved fruitless, Kaali tells us.

Kaali says he is still not a permanent employee despite all these years of working at the Co-op. The pandemic only worsened the situation when the facility had to remain shut during the Sunday lockdowns. Now that restrictions have been rolled back and the state government recently issued the licences required for snake-catching, Kaali is working again. “The licences came late, though. This is not the season. It’s been particularly hard to track saw-scaled vipers in this heat. They hide as much as possible during the day, so I’ve been catching them at night instead. If the licence had come earlier in the year, when the weather is cooler, the saw scaled Viper would be out in the open and easier to catch.”

The snake-catching can only happen during the licensed periods when the government also sets a quota of the number of each Big Four specimen required. Kaali adds that due to the delayed licence, he hasn't been able to meet his quota for the saw-scaled vipers yet.

Apart from this, he works as a paid field guide to herpetologists when required. “This is the work I want to do, I wanted to preserve this knowledge, that’s why I took it up, but how are homes supposed to run on such low-incomes? Kaali asks.

If you’d like to keep up with the work Kaali does, you can follow him on Instagram at the handle: @ka_li2002