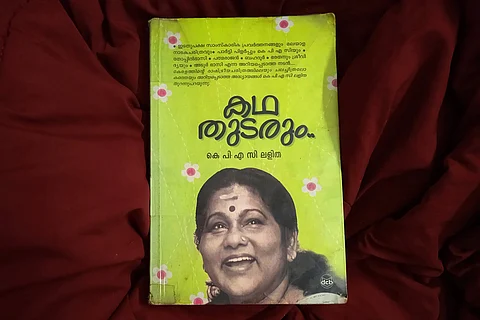

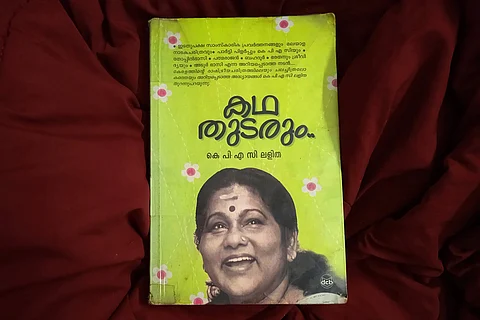

KPAC Lalitha did not have it easy. Not in her childhood, not in her prime married to a genius filmmaker, and not in her final years, fighting many debts and a disease. The easiest years of her life appeared to have come in her youth, when as a passionate theatre actor she travelled with the KPAC — Kerala People’s Arts Club. Those eight years, from her own account, had been so good, she happily adopted the initials into her name. It still seemed like good times in the first few years of her film acting when she led an independent life, moving to a house in Madras. But as she packed on hundreds of films, found fame and recognition as a versatile actor, her personal life was often miserable.

She reveals quite a lot of the difficult life, sometimes drenched in poverty, other times in emotional distress, in her autobiography Katha Thudarum, written more than 12 years ago. Written in a conversational style, it is easy to imagine hearing it in her voice, known to reflect a plethora of shifting emotions. Eulogies were written about the magic in her voice when she died two weeks ago, after months of lying unwell with a liver ailment.

Lalitha would have turned 74 on Thursday, March 10, had she lived.

Her last thoughts, if she had any, might have been of the tasks she left unfinished. At least, that's the idea that you get after 270 pages of Katha Thudarum. There has always been something left for her to do.

Lalitha as a young woman

The first of the responsibilities came to her when she was a little girl, babysitting her brother when her mother was busy. Her father rarely came home. Lalitha wrote, I am sure with a few tears rolling down uncontrollably, of an Onam when she absentmindedly went off to play, forgetting the little sibling. When she came back the boy was alright but the ingredients for the Onam meals, bought with the little money the father sent home, were eaten by stray cats. That day her mother tied her up and beat her a lot. Nine-year-old Lalitha found it too much to bear and made a suicide attempt with pesticide. She survived after a bad vomiting spree.

She doesn't complain about the mother's beatings. Much like she doesn't about the varied difficulties she had to undergo because of others later in life. Lalitha is often simply a narrator of her own life. Such a thing happened and I cried is all she'd say. No cursing, shouting or even whining, which I think she should have done. The book at least was her own space where she had no compromises to make.

The only time Lalitha appeared to go against the tide was in her insistence in joining the KPAC at all costs. Her father, a photographer, had by then been a regular presence at home and nurtured her artistic interests. It is through his work in the Communist Party of India (long before the party split) that Lalitha came closer to the movement and the KPAC. Even as she joined dance lessons (against the mother’s wishes) and began acting with other theatre groups, Lalitha waited impatiently for a way to reach KPAC.

Lalitha dressed for a play

When she did, she was a girl of 16, too thin for roles the KPAC had, but eager to do all that was asked of her. Immediately bursting into song and dance at the audition, she pleased the judges – leading actors of KPAC who took a call. One of them, Sulochana, advised her to gain more weight and Lalitha wasted no time consulting a doctor to figure out how.

She names many actors of the KPAC who mentored her and became dear to her, but the dearest of them all was Bhasi chettan – Thoppil Bhasi, renowned playwright whose works paved the way for the Communist Party to spread wings in Kerala.

Lalitha throws all caution to the wind when she describes what Bhasi meant to her, and states she does not care how that sounds or how people will read it.

She writes little about the first time she went on stage for KPAC – mentioning the plays rather than the roles and her feelings about them. Survey Kallu, Mudiyanaya Puthran, Puthiya Akasham Puthiya Bhoomi, Aswamedham were among her first plays.

At one point, she wanted to act in films but Bhasi had discouraged her. Then again, it was he that later brought her to films. Bhasi was then busy writing scripts for movies. Lalitha’s first role came in Koottukudumbam, a film by Sethumadhavan, adapted from one of Bhasi’s plays. Lalitha writes how naïve she was back then, scared by tales told by a senior colleague about the director chiding the actors in public. She went to Sethumadhavan to say she was going back and didn’t want to be in films anymore. She spilled the story she heard and he ended up laughing at her. He had to shoot the first scene without letting her know it was on camera to make it easy for her.

After that, Lalitha settled comfortably into the world of films, slowly withdrawing from theatre. By then the Communist Party had split into CPI and CPI(M) and there were repercussions in KPAC too. Ummar (late actor) and Sulochana were among those who parted ways with the KPAC because of the split. With old actors gone, Thoppil Bhasi getting busy with films, and a lot changing for the KPAC, Lalitha didn’t feel it was the same anymore.

Breaking her chronology in the book, she jumps to the part of her relationship with director Bharathan, the man she’d eventually marry. At first, she had been a supportive colleague and a ‘hamsam’ in his relationship with actor Srividya. Later, when they broke up and stories began surfacing about Bharathan and Lalitha, he appeared at her door and asked: “Shall we take that seriously then?”

Lalitha and Bharathan

They did. Bharathan’s parents first opposed the relationship but later came around to it. Bharathan was then slowly rising to be the legend he would be known as. Thakara, his film with Pratap Pothen in the lead, sealed it, Lalitha writes. She dedicates several pages about the shifting fortunes of the film. Lalitha writes in detail about many of Bharathan's films, even while she has little to share about her own enviable body of work. It is like she sidelined herself in her own book, a practice she followed in her life, placing Bharathan and his needs before anything else.

Lalitha never points fingers but as she narrates the many episodes of Bharathan's wayward ways—excessive drinking, insulting her in public, and having affairs—you wonder what she really thought about any of it. The narrative takes the tone of a bemused parent, brushing it all off as the pranks of a silly teenager. Once, when he leaves her stranded while going to an award show and gets drunk, she takes a taxi and follows him there. But as she painfully says "it was better to buy me some poison," he retorts: "It would have only cost you the cab fare to buy that poison". Lalitha has written it off as a "joke" — this is how Bharathettan is.

She didn't have a role in all of Bharathan's films, but Sathyan Anthikad, another director who rose in the 80s, always had a character for her, Lalitha writes. It’s an observation made without an ounce of self-pity. At one point, you wonder if she really did enjoy film acting as much as in her KPAC days. For long periods, she stayed away from it, for the family— looking after the children when they were young. She does not seem to resent this. Even having to serve the many guests of Bharathan day in and out is written matter-of-factly. Or else, it is too obvious, and she doesn’t need to state what was wrong.

Lalitha, Bharathan, Siddarth and Srikutty

Lalitha often bares herself as a conservative woman, anxious about astrology and horoscopes and spending much to satisfy the whims of a patriarchal society. Especially, when it is her daughter Srikutty's wedding, an event in a hurry that happens when the daughter is about to go to the US for a job. She adds several more lakhs of rupees to her piling debts with a lavish wedding.

All through her adult life, Lalitha was in debt. There are many pages that describe how she had to keep borrowing money for the family's many needs—building a house, running it, Bharathan's expensive tastes and so on.

She thanks a number of people who had stood by her through the years—co-actors, friends and family. But she reveals she could not stand Adoor Bhasi —a popular actor and comedian of the 60s and 70s Malayalam cinema. He had wrecked her many opportunities, she writes, and behaved lecherously when visiting her home drunk.

In all, she seems to have been a very tolerant woman, as a wife and mother. By the time the book ends, Siddharth, her son, who has started making films, is married and she thanks her stars that she is done with her responsibilities. But she had to face many more tribulations later on including a life-threatening accident that Siddharth met with. Poor Lalitha, even as she somehow made both ends meet, borrowing money and working without break, always thought she could pay off all her loans and find peace again. She simply seemed to accept the difficulties and not overthink it, and that must have kept her going through the decades.