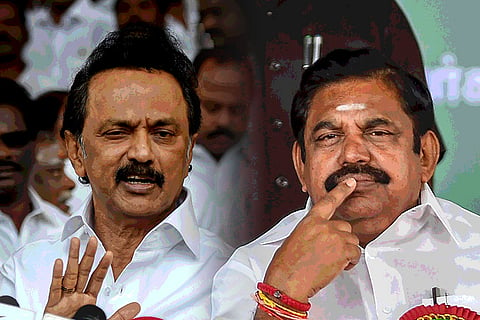

The DMK and the AIADMK released their 2019 Parliamentary Election manifestos on 19 March. From an environmental and long-term sustainability perspective, neither document goes far enough to deal with real issues. Neither, for instance, deals with the elephant in the room – climate change or so much as mention it in their election documents. However, if attention to detail and arguing out a case for the poll promises are any criteria to judge the documents, AIADMK's document falls flat without even trying. Meanwhile, the DMK's manifesto actually contains language that gives some cause for relief and even celebration.

The documents produced by both Dravidian parties laud big infrastructure and technofixes, and are predictably trite for that reason. Long-distance water transfers by interlinking of rivers, fast multi-lane roads, conditional nod to nuclear power plants, big, unimaginative grid-connected electricity generating solar power plants and desalination plants are all part of both documents.

Positioned as though they are revolutionary solutions to long-standing problems, each of these is an intervention that will generate a host of unmanageable problems and will take us away from real solutions.

This environmental critique of the manifestos of the two parties may seem one-sided, and the author runs the risk of coming across as a DMK loyalist. But the fact is that the AIADMK's manifesto offers little material to critique environmentally beyond stating that the party does not appear to believe that an environmental perspective is important.

The DMK's poll document, on the other hand, appears to be informed by feeling the pulse of the people. Whether it actually reflects the party's sentiments or not is a question that remains to be answered.

While there is much to lament about even in DMK's poll manifesto, it is the positive aspects that deserve attention. For the first time, perhaps, a large – though regional – mainstream political party has celebrated values espoused by common people questioning the very meaning of development. In today's context, development means only one thing – paving over or disturbing open-to-the-sky, unbuilt and natural infrastructures to create artificial infrastructures of commerce.

Whoever drafted the DMK document has revalourised two lost principles that have immense value in our times of faltering democracy and failing ecology – namely, people's consent for “development” projects and secondly, the value of the unbuilt infrastructures of open earth economies such as farming over built infrastructures.

On the built versus unbuilt

Knowingly or unknowingly, the manifesto strikes at three founding pillars, and the most destructive aspects, of the current model of development – paving or building over open earth in the name of infrastructure development, fossil fuel extraction and mining.

DMK's document celebrates open and unbuilt spaces and endorses people's opposition to the diversion and paving of farmlands. The credit goes to Tamil Nadu's residents who have in recent times waged a pitched battle against several big “development” projects – sand mining, nuclear plants, coal-fired power plants, highways and expressways, ports and hydrocarbon extraction.

Recognising the importance of arable lands to India's food security, especially with the country likely to become the most populous nation in the world, DMK promises to urge the Central Government to pass a law to protect farmlands.

Additionally, it recommends that agricultural lands should not be disturbed for projects such as hydrocarbon pipelines and electrical transmission towers that face the ire of farmers.

DMK's endorsement of people's arguments against the Chennai-Salem 8-lane Expressway is noteworthy. The manifesto records that the controversial proposal pushed under the Bharatmala Pariyojana will disturb 8 hills, 154 big irrigation tanks, 314 ponds, 300 acres of forests, 30,000 coconut trees and 4000 wells. It has rightly observed that the Expressway will harm the livelihoods of thousands of local people, and clarifies that DMK does not support this project.

Curiously, the AIADMK, which has been violently aggressive in pushing the project as an economic lifeline of Tamil Nadu, makes no mention of this Expressway proposal.

DMK's document proposes a review of the national mining policy to tighten environmental safeguards, correctly noting that indiscriminate mining has scarred the landscape and harmed ecological integrity.

Cauvery Delta: Protected Special Agricultural Region

Recognising the threat posed to livelihoods and food security by diversion of the delta's fertile agricultural lands for non-agricultural purposes, DMK promises to urge the Central Government to enact a special law declaring the delta to be a Protected Special Agricultural Region.

Elsewhere in the manifesto, it specifically targets ONGC's oil and gas wells for groundwater depletion, seawater intrusion into aquifers and degradation of farmlands. DMK claims it will urge the Centre to give up plans for onshore exploitation of hydrocarbon reserves in the delta region. This is huge. Extractive industries, particularly of fossil fuel, have no future and also rob the lands they operate in of a healthy future.

If handled with care, these declarations have immense potential to convert the delta districts into a demonstration ground for people-centred development with positive environmental dividends in the near and long-term. While today's agriculture – an industrial, water and chemical-intensive exploitative exercise – is unsustainable and rooted in feudal and caste perversities, it does not have to remain so. The skills and the interest to transform agriculture into a labour-intensive and ecologically meaningful economy have already reached a critical mass in Tamil Nadu.

Agriculture can be practised in an environmentally friendly manner. But hydrocarbon extraction can never be environmentally benign.

The massive uprising of youth and citizens during the Jallikattu protests highlighted the centrality of agriculture to the Tamil identity. The delta, with its prominence in the Sangam era literature, with agriculture as its economic and cultural mainstay, is a great place to grow a development ethic that honours farmworkers, nurtures agro-based economies and values open, unbuilt spaces as infrastructures of resilience and sustenance.

The mention of agro-biodiversity and farm scientist Nammalwar, and the declared commitment to natural farming methods and produce suggest that there is room for engagement to upscale the agricultural experiment into a full-fledged landscape scale model.

The promise of a central scheme to cultivate palmyra forests to improve ecological resilience and create a livelihood base for the rural poor also holds out tremendous potential for an alternative economy that strengthens ecological resilience.

Not all is Green

While Tamil-ness and social equity have always been values invoked by the DMK, it is refreshing to see a party that has presided over much ecological destruction in Tamil Nadu and headed two disastrous innings in the Union Environment Ministry make so much environmental sense in one document.

That is not to say that there are no disturbing aspects to the DMK manifesto. But the reason for dedicating so much space to the positives is two-fold. First, environmentally damaging schemes are what we have come to expect of mainstream political parties. So that is not news really. Second, it is not often that one sees deep-rooted declarations on environment that represent significant value shifts in the way “development” is defined.

The radicalness of the declarations on agriculture were blunted by DMK's ill-informed opinion on irrigation and water, which is in line with the thoughts of its arch-rival AIADMK. Both the adversaries underscore the interlinking of rivers across states. This is problematic for a number of reasons. It inscribes the notions of surplus and deficits, which are essentially economic concepts, to river basins and ecology. It assumes that all needs of all people in “surplus” basins have been fully met, and that they will willingly give up their “surplus.”

It assumes that the “surplus” serves no ecological function by flowing to sea. By threatening to trap every drop of water before it is “wasted” by reaching the sea, the two parties deny the very dharma of rivers which is to confluence with the sea. If freshwater flows to the sea declines or stops, seawater flow into the rivers will follow.

The emphasis on surface water and rivers with no mention of schemes to regulate, replenish and harness ground water in either manifesto exposes how the two parties are out of touch with reality. A World Bank study reports that “More than 60% of irrigated agriculture and 85% of drinking water supplies are dependent on groundwater.”

There is no dearth of destructive schemes mentioned in the manifesto. One can see the hand of former Shipping Minister and Environment Minister TR Baalu in the projects such as the revival of the Sethusamudram Canal project, a major port in Tharangambadi, development of road infrastructure to decongest Chennai Port, and a sealink connecting Chennai Port to the Manali petrochemical industrial area. These will be flashpoints of conflict with the region's fisherfolk. That is certain.

Notable in its absence, and disturbing for that reason, is any mention of the future of Sterlite in Thoothukudi, or the dangerous trend of criminalising dissent, including for environmental reasons. One would think that the spate of police violence against farmers, fishers and other citizens protesting to protect the environment, and the disappearance of well-known environmentalist Mugilan would have prompted some comment on protection of human rights defenders.

Another noteworthy absence is about the developmental threats facing the fisherfolk and the coast. Across the country, the coast and coastal commons are the sites of massive land alienation and degrading land use change. The Coastal Regulation Zone Notification, a delegated legislation supposed to protect fisherfolk and the coast, has been gutted out to irrelevance. While the DMK promises Scheduled Tribe status to fisherfolk, it fails to recognise that existence of sea tribes hinges on the integrity of a healthy coast and sea. The protection accorded to farmlands that produce food is not accorded to the sea and the coast.

Democracy and People's Consent

Time and again, the DMK document refers to public sentiment against different “development” projects and takes positions against the projects informed by such sentiments. In a democracy, that is a welcome position.

The party's articulation of its position on nuclear projects is curiously worded, but still worthy of engagement. It states that DMK will advocate for a policy that nuclear projects will not be set up without the consent of local communities, and that the electricity generated from such projects would have to be dedicated to the district within which the project is located.

Given the pathetically low expectations that one has of political parties, DMK's manifesto contains much that is worth engaging with. AIADMK's poll document, however, held no pleasant surprises and lived up to its pathetically low expectations.

Views are author’s own.

Nityanand Jayaraman is a Chennai-based writer and social activist. He is part of the voluntary anti-corporate collective Vettiver Koottamaippu.