On many evenings, Shantha saw her two young neighbours walk down the long garden path that led to their Baker model house in a rickety lane of Poojappura. She had sold them the land to build a home in Thiruvananthapuram more than 50 years ago. Radhalakshmi and Padmarajan had just been married then. Years later, Shantha would tell Radha, that the two of them – when they walked together – looked like the couples in those movies that Padmarajan wrote. Then and now, Padmarajan has been credited with creating some of the most beautiful romantic dramas in Malayalam cinema – Thoovanathumbikal and Namukk

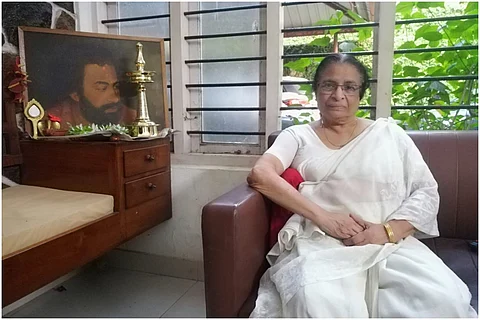

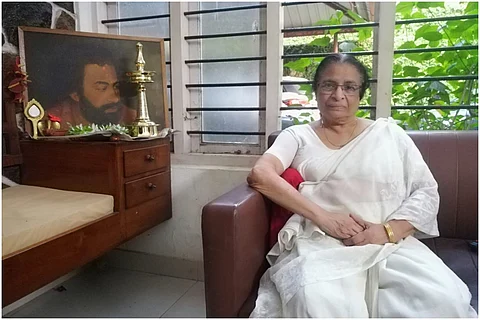

“There is one tale I haven’t told anyone yet. This is soon after I had to resign from the All India Radio station in Thrissur, where I met him and fell in love,” says Radha, sitting on the couch of the high-ceiling living room they once built together.

A year after she joined work, the family learnt of her relationship with Padmarajan who was also employed at AIR Thrissur. They made her resign and go back home to Chittoor, Palakkad, where Radha lived in a large nalukettu with her three siblings and parents.

“I swallowed pills in an attempt to take my life,” she says, after all these years. She was only 21.

She was playing chess with a cousin, Monu, who noticed ‘chechi’ swaying and nearly falling off her chair. The family doctor was called in and Radha lived to tell the tale. She was sent off with Monu and family to their house in Calcutta, and then to Madras where her brother lived. They thought it would bring the change she needed. But in Madras, she met Padmarajan again. His sister Padmavathi lived there.

The family realised there was no splitting these two. In 1970, three years after Padmarajan got a transfer to Thiruvananthapuram, Radha and he got married.

“In the early days, he would write in a room upstairs the house. Many of these long windows in the house are his contribution to the design. But afterwards, when we had kids, he would go to a hotel in Kovalam or Veli and work alone. He couldn't be disturbed when he was writing, unless it was urgent. After a while, we bought a flat in an apartment building in Vazhuthacaud and he would go there to write,” Radha says.

She used to write too, before marriage. The first piece she wrote was an ‘adaptation’ of a novel called Kalangiya Kannukal when she was in class 4. Her father had read poetry to her and there were weekly magazines at home – Mathrubhumi, Manorama, The Illustrated Weekly, Sports and Pastime.

Away in Muthukulam, Haripad of Alappuzha, Padmarajan grew up, a son who was close to his mother. “He had sores in his body as a child and was on his mother’s lap all the time. He couldn’t go to school till he was seven years old and then he joined class 5! He was so brilliant, he heard his elder brother read out loud and learnt the texts even before he knew how to write,” Radha says.

As a young man of 20, he published his first short story Lola Milford Enna American Penkidavu, after reading an American guide his sister’s husband, Dr CN Pillai, brought him once.

He was the sixth of eight children, the youngest of four sons, two sisters above him and two below. One of them – Padma Prabha – lives next door and is now Radha’s closest companion. Only that morning, the two of them went to get the lamp cleaned to place in front of Padmarajan’s photo next to which Radha sits through the interview. “Will you get us both?” she asks, looking at his photo, when I take out the camera.

There are pictures across the long walls, the couple in different stages of their marriage, the two children all grown up and with their families. One of the grandchildren, a curly haired little one, can’t resist coming over to whisper to the grandmother now and then.

“Where was I?” Radha asks. Her memories of Padmarajan flow from story to story, one year to another far away. The '60s, '70s, '80s all appear to come out together.

Radha stopped writing when she met Padmarajan and read the stories he wrote. “I realised that those of us in the north (of Kerala) wrote the way we spoke while they – in Alappuzha -- have a literary tongue,” she says.

Rarely, she would write a story and show it to Padmarajan who would smile, but say little. In turn, he showed all that he wrote to her. “Not the stories he wrote, he wouldn’t let anyone have a say on it. But the scripts of films, he would first show me and we would start discussions and debates.”

For Thingalazhcha Nalla Divasam, Radha contributed so much that her name too featured in the credits. At other times, it would be a story she told him, of someone she knew. Poor Radha had no idea that Padmarajan would write the story of her friend who had an unfortunate end, when she told it to him in their radio days. “I knew it only when the story got printed!” she says. That story was also the basis of the 1978 film Shalini Ente Kootukari, directed by Mohan.

“And also Novemberinte Nashtam, which is what I always cite as my favourite among his scripts,” Radha says. What got least noticed and deserved more attention, in Radha’s opinion, is the film Arappatta Kettiya Gramathil, which starred Mammootty, Nedumudi Venu and young Ashokan visiting a brothel in a village. Mammootty’s character, she says, was based on a friend, and Ashokan’s was a lot like himself. Padmarajan put Radha in a story too, it is believed, in one of his most celebrated novels – Nakshathrangale Kaval. Radha laughs when she says, “People say the young protagonist is based on me.”

Watch: Scene from Arappatta Kettiya Gramathil

It’s hard to choose one of his stories either as a favourite or as the one she least enjoyed, given that there were so many. He wrote 36 scripts, directed half of them, wrote short stories and novels. “All that while he also had the job of radio announcer! He kept it till 1986, on his brother-in-law RB Unnithan's advice that if he worked for 20 years, he’d get a pension. So he worked for 21, and then took voluntary retirement. I still get that pension,” Radha says and looks sombre for a moment.

But pleasanter memories arrive from another corner of her mind. How Padmarajan would ask everyone to tell him the interesting stories they come across and then make movies out of it. A nephew -- Dr Narendra Babu -- in the United Kingdom told him about the story Namukku Gramangalil Chennu Raparkam (Let’s go live in the villages) by KK Sudhakaran and Padmarajan scripted his iconic film Namukku Parkkan Munthirithoppukal based on it.

Watch: Proposal scene from Namukku Parkkan Munthirithoppukal

A friend, Rama Varyar, told him an incident that inspired him to write Rathinirvedam, which was later made into a film by director Bharathan. A real life story narrated by another friend - Sunny Radhakrishnan - led him to write the script of Sathrathil Oru Rathri, directed by N Sankaran Nair. “Of course, it is a small part that comes from real life, the rest is imagination,” Radha reminds you.

The first film Padmarajan directs is Peruvazhiyambalam, a novel that was serialised in the Mathrubhumi magazine. "Our first producer Prem Prakash had asked for its script, but he said he wanted to direct it himself,” Radha says.

If you glimpse through his filmography or list of literary works, it is remarkable that a man wrote all that in his 45 years of life. And that too while keeping an office job and having a family. He also read a lot. There was never a day when he didn’t have a book with him. “During his announcer days, he would carry a book to read during the break time. In Thiruvananthapuram, he’d always go to Current Books. That’s where the friendship with director Sankaran Nair began," says Radha.

It is Padmarajan’s elder brother Padmakshan who passed on a love for English books to him. He had been in the army and used to joke that because of his brother’s and Radha’s relationship, he too would need to get married soon since he was older by 10 years. Among all that he read, Padmarajan loved his Marquez the most. In Malayalam, he adored MT Vasudevan Nair’s works as a young man. When he got older, he was fascinated by Uroob, VKN and Basheer.

Radha read too, MT was her favourite author too. But she took years to write again. When Padmarajan passed away after an unexpected cardiac arrest at a hotel in Kozhikode, the media turned to his wife. She spoke in many interviews, shared memories of the beloved director who left the world too soon. Literary critic KP Appan, who came across these interviews, told her, “Radha, you should write.”

Radhalakshmi has since written six books, her first was Padmarajan Ente Gandharvan. That was the name of his last film – Njan Gandharvan – I, a celestial being.

She wrote articles in magazines. She became president of the SMSS Mahila Mandiram in Poojappura, a walk away from the house, she points a finger, walking out to the front yard. There, before her, is the long stretch of garden path that she walked on some evenings before COVID-19 struck, with the memories of the man she has never stopped thinking about three decades after his death. If Shantha was there, she’d say, they – she and her memories of him – still walk like the couples in his movies.