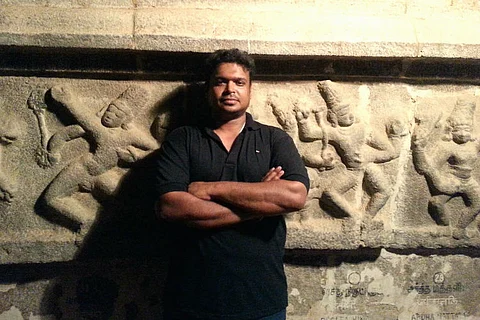

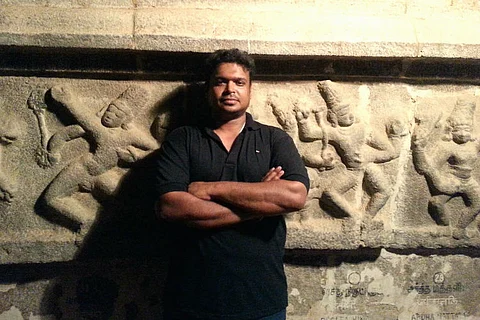

Tucked away in the office of a shipping company in Singapore, Vijay Kumar flips through catalogues and photos in his spare time, often late into the night. This research is what has helped expose international smuggling rackets running into millions of rupees. Vijay’s last catch, or rather the last catch he helped the police net was Deenadayalan, a liaison of a prominent idol smuggler.

By day, Vijay is the general manager of a reputed shipping company, but off duty, he documents several idols that have been missing from India’s temples and colonial loot. It’s a 24/7 passion, regardless of his salaried job.

|

It all began with an ardent interest in Chola kingdoms and his grandmother’s stories during his childhood. “I was also taken up by the Tamil novel Ponniyin Selvan,” he says. The novel was a fictionalised historical drama that centred around the Chola rulers.

But things took a decisive turn when Vijay started a blog called Poetry in Stone 2010. He and other bloggers collected images and information about artefacts and idols and built up a repository of information that was accessible to the public.

In his experience, archaeology experts tend to hoard their knowledge or put it scholarly papers that read like Greek or Latin, incomprehensible to the lay person. “Some of experts have even written in catalogues of many art dealers who are now jailed,” he rues.

With the blog, he and others began to actively compare photographs of idols and artefacts from temples in India with images of art collections in museums and galleries across the world, looking for stolen artefacts among them.

Initially, scholarly circles and law enforcement did not take Vijay seriously, but he didn’t back down. Amateur though he may be, pouring over documentation has made a force to reckon with - he rattles off names, dates without a pause and can identify idols with thoroughness.

Recognition came in 2011, with the arrest of New York-based gallerist Subhash Kapoor for allegedly running a $100 million smuggling racket. His role was recognised by Interpol. While Vijay believes Kapoor will be out soon due to the laxity of the police, he doesn’t discount the fact that the Indian agencies’ crackdown is just the start of many skeletons tumbling out of the cupboard.

After this, he continued to research artefacts as did his fellow bloggers. One such blogging assignment required him to trace the evolution of the ardhanari form of sculpture. “I picked a personal favourite - the Vriddhachlam Ardhanari,” he says. To his shock, he was surprised to see that the Art Gallery of New South Wales in Sydney had the idol. Back in Vriddhachalam, the Virddhagesevarar temple authorities were blissfully unaware that the idol they had was a fake, Vijay said.

Vijay’s work however, hasn’t earned him any fans. His dogged persistence has driven many experts and even the police up the wall. What made him popular in the mainstream is not his capture of Subhash Kapoor, but the return of a Ganesh idol which was one of over 200 handed over by the US government to Prime Minister Narendra Modi in June.

In 2013, a member of the India Pride Project, which was co-founded by Vijay, traced the 1,000-year-old Ganesha idol to the Toledo museum in Ohio. “We matched the idol’s blemishes to the photo archives of the French Institute at Puducherry,” Vijay says. The photographs were taken in the 1960s when the original was still in the temple in Sripuranthar, in Tamil Nadu’s Ariyalur district.

Writing to the museum elicited no response. They then wrote to the Indian Embassy and Ambassador, to no effect. But here’s what got everyone to notice – they uploaded a YouTube video titled ‘Remover of Obstacles’. The Toledo museum eventually returned the idol, saying they wanted to the right thing and that they did not want stolen objects.

Vijay says that besides idols, smugglers find it easy to take terracotta artefacts out of the country. Terracotta idols and pots are broken into pieces and transported from India to Hong Kong, Bangkok, Dubai and through London and Switzerland to avoid detection. Guess where it’s easy to smuggle them out of? Switzerland.

The Swiss Freeport, he claimed was where many of these stolen items ended up. Since then, freeports have sprung up everywhere, providing looters a secure location to fence the stolen artefacts.

So how high a priority is idol smuggling for the Indian government? India has just one dedicated police wing looking for such stolen idols – the Tamil Nadu Stolen Idols unit, which functions under the Economic Offences Wing. “The Idol wing has gone from 100 officials, to 28 and now 8. Officials often approach this as a punishment posting,” Vijay says.

To drive the point home, Vijay says that Italy in contrast, as about 3,000 officials dedicated to the recovery of stolen art. As a result, the Italian government has recovered over 7.8 lakh idols while India’s figures stand at a measly 19, Vijay claims.

The web of artefact smugglers is far more complex than the currently exposed skeletal network, Vijay says.

“It involves many conspirators and compliant individuals. Our biggest enemy is compliance. We want to make sure that the next time someone wants to buy an Indian idol or artefact, they know not to mess with us,” he says, with a sting in his voice.

Don’t the years of research dissuade him from keeping it up? “I believe in vigilante justice and don’t necessarily need to be part of the system to help it. I want to show that Indian art is no longer fair game. If you touch it, we will come for you. Maybe the gods wanted to come back and chose a hard nut like me,” he quips.