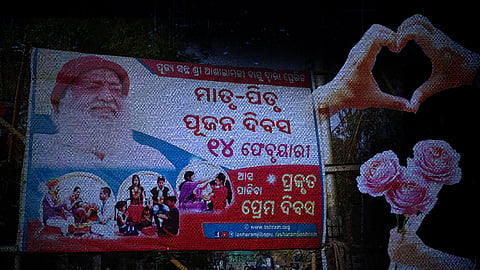

Every year on February 14, while much of the world marks Valentine’s Day as a celebration of love and companionship, a parallel campaign quietly but firmly resurfaces across parts of India. Posters, banners, social media posts, and WhatsApp forwards urge people to observe Matri Pitri Poojan Diwas or Parents’ Worship Day instead.

Initiated in 2007 by self-styled godman Asaram Bapu, the day is projected as a moral and cultural alternative to Valentine’s Day. On the surface, it appears to promote respect for parents and Indian values. But beneath this carefully constructed narrative lies an uncomfortable reality. The man whose name is attached to this so-called moral observance is a convicted rapist sentenced to life imprisonment. He is currently out on interim bail on medical grounds.

The annual promotion of Parents’ Worship Day is not an isolated cultural exercise. It forms part of a larger strategy to repackage Asaram Bapu as a cultural reformer rather than a criminal. By repeatedly foregrounding his ‘contributions’ to Indian tradition, his followers attempt to push his convictions into the background. Celebrating February 14 thus becomes less about honouring parents and more about managing a damaged public image.

A similar exercise unfolds every December 25 with the observance of Tulsi Pujan Diwas, introduced in 2014 by Asaram Bapu. Devotees worship the tulsi – a plant considered sacred by Hindus – and prepare offerings, with the day being presented as a cultural alternative to Christmas. Once again, the focus shifts from sexual violence, exploitation, and judicial findings to culture, identity, and nationalism. Festivals become tools not only of religious expression but also of reputation laundering.

Asaram Bapu’s criminal record is not based on allegations alone. In 2018, a court in Rajasthan sentenced him to life imprisonment for raping a minor at his ashram. In 2023, another court in Gujarat convicted him in a separate rape case involving a woman disciple and again awarded life imprisonment.

Several other cases relating to sexual assault, criminal conspiracy, and exploitation have been registered against him and members of his organisation. His son has also been convicted of rape and sentenced to life imprisonment. These verdicts came after years of investigation, survivor testimonies, and judicial scrutiny. Yet, belief in his ‘divinity’ continues to survive.

This phenomenon is not limited to one ‘godman’. Gurmeet Ram Rahim Singh, convicted in rape and murder cases, still commands fierce loyalty from sections of his followers. Nithyananda is absconding after facing allegations of sexual assault and exploitation, yet continues to operate spiritual networks through devoted supporters. Chandraswami, accused in multiple criminal cases in the past, remained influential for decades. The pattern is consistent. Allegations emerge. Evidence is presented. Courts deliver verdicts. Faith remains largely intact.

Women are often at the centre of this exploitation. Many approach these ‘gurus’ during moments of vulnerability, such as illness, infertility, marital distress, financial hardship, or emotional trauma. Instead of being guided toward medical professionals or counsellors, they are told that devotion alone will cure their suffering. Touch is normalised as blessing. Isolation is framed as spiritual instruction. Silence is demanded in the name of faith. What is presented as healing frequently becomes a gateway to abuse.

Survivors across different cases have described similar methods of manipulation. They are told obedience proves devotion. They are warned that speaking out will invite divine punishment. Their trauma is explained away as karma. Such tactics succeed because society continues to place godmen beyond suspicion.

The reach of ‘baba culture’ is not confined to villages or underdeveloped regions. Posters and banners of convicted godmen are visible in urban public spaces, in markets, railway stations, metro premises, residential colonies, and affluent neighbourhoods. Posters featuring Asaram Bapu promoting Parents’ Worship Day have appeared in cities including Delhi, Navi Mumbai, and Bhubaneswar.

Matri Pitri Poojan Diwas is observed in states such as Chhattisgarh, Maharashtra, Haryana, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, and Odisha, where posters and banners encourage people to mark the day instead of Valentine’s Day. Tulsi Pujan Diwas is similarly promoted in some parts of the country as an ‘Indian alternative’ to Christmas.

The images of these godmen circulate freely on vehicles, walls, and social media. This visibility sends a chilling message. Conviction does not end legitimacy. Jail does not end influence.

The contradiction becomes sharper when contrasted with India’s prison reality. Thousands of undertrials remain incarcerated for years for minor or disputed offences. Many are eventually acquitted after losing decades of their lives. Meanwhile, influential godmen are perceived to receive repeated medical bail, interim relief, or sympathetic consideration.

Even when courts convict, social power cushions the fall. For survivors of sexual violence, this environment is crushing. Justice is not only about punishment, it is also about public acknowledgement of harm. When a convicted rapist continues to be worshipped, society signals that faith matters more than a woman’s suffering.

Blind faith persists because it is carefully cultivated. Charismatic preaching creates emotional dependence. Large organisations control narratives through publications, events, and digital campaigns. Cultural nationalism frames criticism as an attack on religion. Over time, belief becomes identity, and identity becomes untouchable.

This reality corrodes the very idea of Indian spirituality. India’s philosophical traditions emphasise questioning, reasoning, and ethical living. True spirituality demands compassion and accountability. It does not demand surrendering conscience.

Critiquing baba culture is not an attack on Hinduism or Indian culture. It is a defence of both. Culture cannot be built on the denial of sexual violence. Tradition cannot survive if it protects predators. Faith loses moral meaning when it becomes a shield for criminality.

As long as convicted godmen continue to be celebrated as cultural icons, baba culture will remain deeply rooted in Indian society. Not because it reflects India’s true spiritual heritage, but because it exploits emotional vulnerability, fear, and identity politics. Ending this culture requires more than court verdicts. It requires collective moral courage to say that no one, however powerful or popular, is above justice.

Sriyanka Sahoo is a PhD scholar in Journalism and Mass Communication at Utkal University, Odisha. Her research examines media portrayals of crime against women and the construction of gendered narratives in Indian media.

Views expressed are the author’s own.