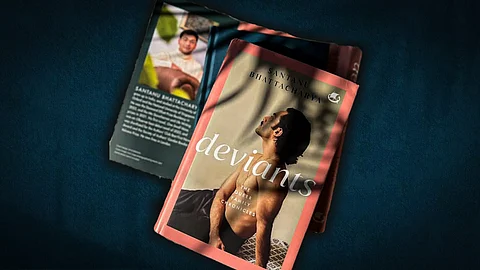

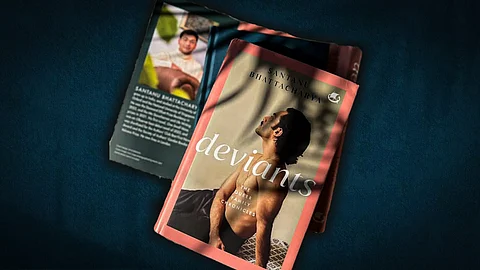

Santanu Bhattacharya’s Deviants begins quietly – three queer lives unfolding in different decades, linked by blood, but separated by time. There’s no grand declaration or dramatic moment of coming out. Just three men trying to live, love, and speak.

The narrative maps the intimate mindscapes of Sukumar, Mambro, and Vivaan, all of them from the same family. Their lives are braided together–“a delicate bloodline of forbidden love, across three generations,” in a country that keeps shifting the goalposts of acceptance.

The book begins by saying, “Each of us really has only one story to tell,” and goes on to explore that one story of love and aching isolation across generations.

Each of the three men navigate their queerness in a different India. Everyone's story is distinct, yet interwoven so seamlessly, that we remain emotionally tethered to all three timelines.

Sukumar, in the 1970s, living under the shadow of Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code (that criminalises same-sex relationships), finds stolen moments of intimacy in the anonymity of Calcutta’s docklands. Mambro, a young man in the 1990s, wrestles with desire in a repressive college hostel and clutches at the fragile language of self-acceptance against the backdrop of many legal battles that defined queer rights in the next decades. Vivaan, a teenager in 2024, navigates queer dating apps and watches the Supreme Court debate marriage equality, all while trying to find his footing in the world around him.

The book brings out the shared sense of marginalisation, which remains the same across timelines, irrespective of how far the law or society may have seemed to come. It also narrates how queerness can echo in a family through silences, gestures, and the quiet hope that someone down the line might have a life that those before them could not have.

Through Vivaan’s eyes, we also get a glimpse of how Gen Z processes ‘wokeness,’ legal disappointment, and the freedom and fatigue of identity politics. An unexpected but quietly powerful thread in the novel is its exploration of Artificial Intelligence (AI).

Vivaan, the youngest of the three protagonists, befriends an AI bot, his confidante for thoughts he cannot share with anybody else. Their relationship soon becomes irreversible, yet limited by its intangibility. This subplot is especially intriguing against the backdrop of a world that is becoming dependent on AI for therapy, companionship, and emotional needs.

It also subtly reminds us of Spike Jonze’s film Her, where the lines between intimacy with a bot and real human connection blur, until the illusion inevitably falls apart.

Deviants also fascinates with its usage of language, which in itself becomes a character. The novel keeps returning to how life saving it is to have the language to communicate one‘s feelings.

Mambro, at one point, talks about how hard it is to speak about queerness: “You don’t know how to form the words, your language has no shared vocabulary for a conversation like this.” For him and Sukumar, the absence of language is a burden that they were destined to carry.

But for Vivaan, there are words. They are imperfect, evolving, but present, and that makes a big difference. It doesn’t solve everything, but opens a door. As Mambro himself says: “Maybe that is the only thing that has become better… We have words now. Laws will be made and unmade, promises kept and reneged on, the haters will never go away, and everyone else will sit on the fence and watch the show. But we have the language now to tell our stories.”

Deviants reminds us that language is not just a tool for expression, it rather allows people to exist fully in their world. This idea is also woven into the very structure of the novel, through the distinct narrative voices given to each character: Sukumar’s story is told from a third-person point of view (likely that of Vivaan’s), giving it a sense of distance and loss. It is the life of a person who never told his story. Mambro’s voice is internal, as though he’s trying to piece together his life for himself. Vivaan’s voice, on the other hand, is direct, conversational, and witty.

However, for a novel so deeply embedded in the Indian context, Deviants has a striking blind spot: caste and religion are largely absent, surfacing only briefly to talk about how different faiths oppose queerness in similar ways. This missing element is significant.

Love, desire, and identity are not experienced in a vacuum, especially in a country like India. And without acknowledging caste, the book leaves out the ways power and privilege dictate whose queerness is safe, whose is seen, and whose remains buried.

That apart, Deviants is a compelling, intimate, gorgeously written novel. It’s a rare book that lets us see not just queer love but queer lineage–how silence and speech travel through generations, and how every small act of love and defiance builds a world that may allow the next person to breathe a little easier.

Views expressed are the author‘s own.