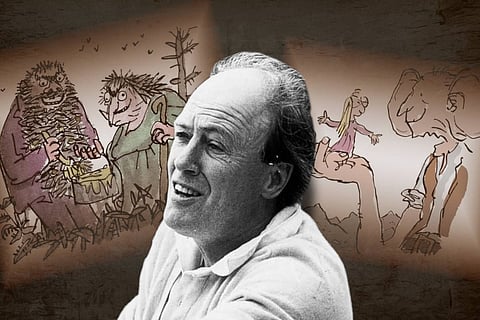

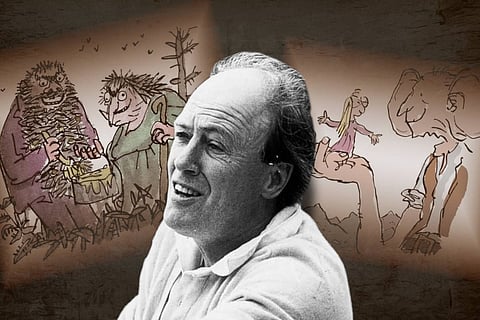

Roald Dahl was not a particularly nice man. He’s known to have made anti-Semitic statements. Some of his characters were based on racist stereotypes. He did not like single older women much. He wasn’t kind to fat people. He was also a brilliant writer. Now, what do we do with his books? Trash them altogether, rewrite them, subject Dahl to a premium laundry service, or continue to read him, warts and all?

The whole brouhaha around Puffin, Dahl’s publisher, announcing that they were bringing out ‘revised’ versions of his books, edited to suit modern day sensitivities, raises an important question about children’s literature. How do we ensure that children are reading books that won’t plant wrong ideas in their heads and pass on offensive stereotypes? Or perhaps, the question should be, ought we?

I discovered Dahl when I was about 13 or 14, and I read his twisted, erotic stories with characters like Uncle Oswald much before I knew that he was also a children’s author who wrote books with Oompa Loompas and BFGs. These adult stories ranged from one about a perfume called ‘Bitch’ that would make a woman irresistible to a man, prompting him to initiate sexual intercourse instantly, to another about a woman who kills her husband with a leg of lamb and feeds the murder weapon to a bunch of unsuspecting police officers. Shocking, I know. My parents should be thrown in jail.

Till I was about 10 years old, I was on a steady diet of picture books from the former Soviet Union, Enid Blyton, and Indian children’s magazines like Tinkle, Chandamama, Champak, Gokulam and Wisdom. My parents – neither of whom had studied in an English medium school – were very particular that both their children learn this aspirational language. A book in my childhood, therefore, was never deemed undesirable. Questions on whether the book was sensitively written, if it had problematic ideas, or if it was age-appropriate never arose.

My brother and I read whatever interested us. From RK Narayan’s gentle, languid Malgudi to PG Wodehouse’s pleasantly foolish ‘idle rich’ of England, Premchand’s translated short stories on the Indian downtrodden to the deliciously murderous husbands, wives and butlers of Agatha Christie – we devoured it all. Roald Dahl was one of the many authors we read and there was only one reason for it – his writing was riveting.

Dahl’s plots are unpredictable, his characters are irreverent, seldom colourless; The adults in-charge are no good – this is a key, oddly comforting sentiment in Dahl’s books for young people. Even when the adults have some sense, like the Grandmamma in The Witches, they do not-so-good things like constantly smoking cigars. The deeper, problematic issues with Dahl’s writing – like his penchant for equating ugliness with bad character – were invisible to me at that age. But I’m sure the messaging seeped into my subconscious, as is the case with any piece of art that we consume.

It’s not that such conversations around Dahl’s books were non-existent at that point. In fact, in the 1970s, Dahl was persuaded to change the description of the Oompa Loompas (Charlie and the Chocolate Factory) who were originally inspired by the African pygmy people, following sustained criticism. As an Indian child and teenager, though, I was blissfully unaware about all these debates, and didn’t even know that a book could be read at so many different levels. It was only after I became a student of English literature – thanks to all the authors I’d read and loved – that I knew this was possible. Not just possible, but necessary.

From sexism in Enid Blyton’s books to colourism in Amar Chitra Katha comics, I learnt to re-read all those books with new eyes. I was surprised to discover that Harriet Beecher Stowe’s anti-slavery novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin had been heavily criticised by African-American people for its patronising tone and stereotyping of their community. I had shed so many tears at Tom’s pitiable fate as a child that it had never occurred to me to doubt Stowe’s writing.

As students of literature, we couldn’t just ‘cancel’ these writers and sit back smugly in our chairs. We were expected to engage with their ideas and add to the discourse around their books. We were expected to contextualise their writing, study the social mores, personal experiences, and beliefs that had undoubtedly left an impact on their work. I learnt to develop my critical ability without feeling the need to hate or reject something. I wasn’t turning my back on these books or writers, I was leaning towards them to look at them more closely. I understood that every writer’s work was a product of their time, culture, and social location, and it was impossible for a subjective work of art to satisfy everyone equally and at every time period. Literary criticism was an art as much as creating literature was.

When I became a children’s writer myself, I was mindful of sensitive representation because I had learnt what to do and what not to do from my favourite authors. Still, I’ve read negative reviews of my books, I’ve had conversations and debates with my editors on characters or storylines over which we disagreed, I’ve made revisions to drafts and sometimes editions.

But as much as I have tried, it’s quite possible that future readers may find problematic ideas in my books. If I’m still alive and willing to engage with the debate at that point — like Dahl and the Oompa Loompas in the ‘70s — and I’m convinced by their reasons to make the changes, that’s all right. The subsequent editions will still be me, they won’t be a lie.

However, if I am not speaking for myself, and someone else is making these changes on my behalf and putting my name to it, it is a dishonest picture of who I was and what sort of beliefs I had. It is an unethical act of historical revisionism. Readings are necessary and welcome, rewritings, without the author’s knowledge or consent, are not. I’d even argue that taking Dahl’s books off libraries in protest of his anti-Semitic views or insensitive language is preferable to pretending he wasn’t dodgy at all by changing his words to our convenience.

The futility of the ‘editing’ exercise becomes more obvious when we take into consideration the fact that sexism isn’t present only in Blyton’s or Dahl’s books – it is present in modern day mainstream cinema, cartoons, detergent commercials, religion, calendar art, just about everywhere. Is the solution then to “protect” children by denying them access to such material altogether or encouraging them to develop their critical ability? After blotting out all the ‘bad’ phrases from Dahl, will we replace all the misogynistic scenes from Rajinikanth’s Padayappa or create a children’s Bible where God made Adam and Eve at exactly the same time? Will we go on making these changes decade after decade until children’s novels become like the Ship of Theseus, with all the parts replaced?

I suspect that our eagerness to control what children should read comes from a place of unwillingness to respect their intelligence. Instead of initiating a classroom discussion on Miss Trunchbull’s aversion towards married women or Georgiana’s insistence on being called George, we would like to hastily end all debate by replacing ‘problematic’ content with sanitised versions. Instead of provoking curiosity in children to read books from different time periods and compare them, we would like to ‘update’ everything to suit our contemporary times. We don’t want to give them the time and space to form their own relationship with a book and its writer – an intensely personal relationship that will change and evolve.

As a children’s author who has been to several kinds of schools across the country, and met children from different social classes and locations to discuss stories and more, I can tell you that most children jump at the chance to voice their opinions. About books, movies, families, society, the world. But are we ready to listen? Or are we going to be the condescending, we-know-best adults that Dahl so wonderfully lampooned in his books?

Sowmya Rajendran writes on gender, culture, and cinema. She has written over 25 books, including a nonfiction book on gender for adolescents. She was awarded the Sahitya Akademi’s Bal Sahitya Puraskar for her novel Mayil Will Not Be Quiet in 2015.

Views expressed are the author's own.