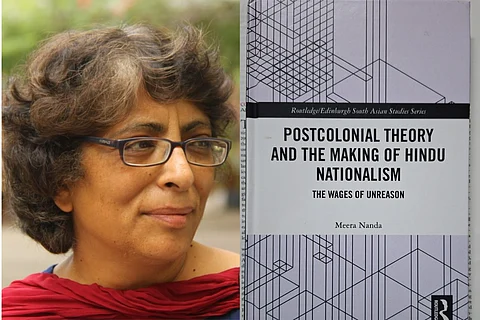

Meera Nanda, philosopher of science, has for some decades been a one-person army taking on assaults on reason and democracy and the Indian Constitution and delivering sound and logical defences of the values of a secular, egalitarian and justice-seeking nation. Her arguments are always meticulously organised and cogent, and presented with incisiveness and precision. She can take on with equal ease the generals or the foot soldiers of the large Hindutva army, from the ideologues dressed as philosophers to dangerous, venom-filled guerrillas who will kill, maim, lie and deceive for what they see as a holy cause.

Her weapons are logic and knowledge, and she persuades through books and lectures. It is an unequal battle, but Nanda is tireless and determined. She is motivated more by patriotism and love of her motherland and culture than nationalistic and jingoistic fervour.

Meera Nanda’s Postcolonial Theory and the Making of Hindu Nationalism: The Wages of Unreason has an epilogue and four weighty chapters. Each of these has a set of notes and references. Together, they probably cover most of the literature pertinent to the areas Nanda is exploring both in terms of its philosophical foundations and its everyday manifestations, as seen in the rites and rituals that performative religion is full of.

Nanda has no problems with the aam aadmi’s need for solace and comfort but targets the doublethink and the ethical blindness of upper-class Indians. Among them are Indians working in universities abroad. There, the universities collect and study everything from the past to understand history rather than endorse past practices. So when pretenders of knowledge exploit institutions that are supposedly open-minded to push their deeply conservative agendas, she is quick to call them out. She does that with panache, bursting every bubble in the body of frothy arguments with the pinpricks of reason.

The book is dense and extremely detailed and has elaborate descriptions and analyses of postcolonial theory. This is from the philosophical end of the spectrum and not the level at which her previous book on post-truth dissected Hindutva. All shades of opinions, arguments and contentions are closely looked at and analysed, and wherever found wanting, discarded with force and finality.

Each of the six sections has a set of notes and list of references. Together, they take the reader through every corner of the philosophy of science and sociology of knowledge, apart from probing relevant ideas in the political and ideological areas of thought. This book is even more elaborate than her solid Prophets Facing Backward (2006). All her other books are slim, but substantial in terms of content. So much has passed since the publication of Prophets that this book had to be thicker and contain her views on the innumerable ideas that have cropped up in the areas she focuses on.

The quarter century since that book was published has been turbulent and Nanda has been alert to every development since, both the gross and the subtle. The main story is about the coming together of two apparently incompatible groups, the Postcolonial Left and the Hindu Right. In pre Nazi Germany the conservative Right had a big role in bringing down the Weimar Republic, which was a constitutional republic and preparing the ground for Hitler. Similarly, the Indian Left has helped prepare the ground for the religious Right.

By attacking the ideas of universality and global human rights, ignoring everything from shared DNA to a commitment to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which India helped draft, the floodgates to magic and myth and mumbo jumbo have been opened. Left-leaning intellectuals once upheld secularism and humanism but have, in the last four decades or so, mated with the postmodernists in metropolitan universities and sneer at words like secularism, science, development and the values of the Enlightenment like equality, liberty and fraternity.

Nanda demonstrates how Hindu ideas based as they are on hierarchy and an ancient idea of a divinely ordained pecking order, are not suited for a modern society.

Not if that society wants to thrive and to provide all citizens with equal opportunities for flourishing. The intellectual Left and the Right team up to deny the poor and illiterate masses of India these chances and instead romanticise the status quo. Sanskrit quotes about ancient Indian wisdom aid them in this.

A distinctive Hindu sensibility is innate in the political unconscious of Indian postcolonial theorists. The gods they invoke, the mythic mode they use to understand history, and the holistic modes of knowing they speak about are all Hindu. “Hinduism is the elephant romping through the postcolonial Ivory Tower that everyone pretends not to see” Nanda writes. The term “swaraj in ideas” sounds fine till you realise that the ideas are illogical and unjust. All that they have going for them is that they are native to India. Nationalism seems to be the first refuge of the hate-filled.

Nanda suggests that she is not competent to speak about deep-seated, unconscious motivations but makes it clear that hatred and xenophobia are among the driving forces of the ultranationalists. The people who speak about the whole world being one family have no problem lynching or slaughtering those they think are different from them. Hypocrisy, it is said, is the compliment vice pays to virtue. The practice of hypocrisy is a full-time occupation for many in today’s India, particularly its political and ideological leaders.

It was said about Bertrand Russell that it was impossible to paraphrase his prose; it was so precise and succinct. This is true of Nanda, too. Like Russell, she is guided by knowledge and inspired by love. Love of both her countrymen and the truth.

There is one significant omission in the otherwise comprehensive criticism of flawed Indian ways of thinking. Just like Trumpians in America, the bhakts in India are indifferent to the dangers of climate change. From the Himalayas to the southernmost tip of the Andamans, all of India showcases the dangers of development schemes that are blind to environmental damage.

The fragility of the land and the rivers and the beaches has been the focus of research, most often undertaken by world-class scientists working in Indian institutions. As the land around them melts, Indians continue to think that everything is solid and permanent. Again, fantasy trumps reality. That Nanda does not focus on this does not detract from the value of an exceptionally excellent book.

At the close of an English novel is a scene where a lot of intellectual imposters have been lined up on a parade ground. A drill sergeant then commands them to stand at attention. Stiff and erect, he shouts his last command, “Diss-Miss-Ed!” Nanda treats the postcolonial brigade with a similar tone of finality. An intellectual dismissal will not have much impact in India. The postcolonials will be back. So will Nanda, we can be sure.

‘Postcolonial Theory and the Making of Hindu Nationalism: The Wages of Unreason’ by Meera Nanda is published by Routledge, New York (2025). Price unstated.

P Vijaya Kumar, a native of Thiruvananthapuram, is a retired lecturer.