Written by Anjali Menon

TW: Mention of suicide

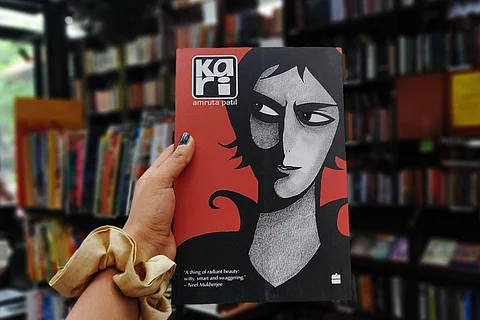

During an evening of food, gossip, and laughter with her flatmates, Kari, the titular protagonist of Amruta Patil’s graphic novel, feels a surge of joy. As the two women flood her with love, casually flirting with her, she decisively tells us, “Make no mistake, there is no such thing as a straight woman.” Kari is a lesbian living in what she calls ‘Smog City’ – the official name is never mentioned, though visuals of maps, railway stations, and the sea allude to Mumbai.

Amruta Patil’s book centres around a queer woman who is trying to navigate a big city, mental illness, and the inescapable heteronormativity that surrounds her. Whether it is at the ad agency she works where a colleague asks if she is a “proper lesbian”, or the cramped apartment which she shares with two other women and their boyfriends, Kari has little space to breathe. ‘Smog City’, as its name suggests, is suffocating.

We first meet Kari in the aftermath of an attempted double suicide along with her lover Ruth. Saved by a safety net, Ruth survives and leaves the city. Kari too is saved, having landed in the city’s grisly sewers. In a moment of gratitude, she makes a promise to the waters to “return the favour”. She thus becomes a boatwoman, who rows to unclog and clean the darkest of waters at night.

The book’s illustrations reflect the protagonist’s inner world – they are largely black and white, with colour brought in sparsely to imply a sense of belonging and home. Patil opens the book with a painting of Ruth and Kari that apes Frida Kahlo’s iconic 1939 self-portrait ‘The Two Fridas’. Completed shortly after her divorce with Diego Rivera, Kahlo had written in her diary that the painting was drawn from her memories of an imaginary childhood friend. It bears the anguish and pain she felt after her separation.

Patil’s use of this imagery becomes a metaphor for how inseparable Ruth and Kari were, and of how we only know of the Ruth that now lives in Kari’s mind. This feeling of alienation that runs through Kari and across the novel is a universal one; it speaks profoundly to the loneliness that women living alone in big cities inhabit. Olivia Laing articulates this in The Lonely City: “Almost as soon as I arrived, I was aware of a gathering anxiety around the question of visibility. I wanted to be seen, taken in and accepted, the way one is by a lover’s approving gaze. At the same time, I felt dangerously exposed, particularly in situations where being alone felt awkward or wrong, where I was surrounded by couples of groups.”

Rife with magical realism and mythological motifs, Kari is a novel deeply interested in death and loneliness. We are never informed of the explicit reasons for the attempted double suicide or Ruth’s exit from the city. The story we are being told is of a reincarnation of sorts, Kari’s second attempt at life. Death still looms in this second life, with Kari’s biggest source of hope coming from a friend who is dying of cancer – befittingly named Angel. Kari feels safest in her company. They become each other’s companions, as one tries to grapple with life and the other, death. “Death will always come to you as a friend,” Angel tells her on her birthday. “Don’t be scared.”

Throughout the book, Patil profoundly explores the concept of decay: the decay of water, decay of the city, decay of the mind, decay of relationships, and decay of life. Many books about Mumbai reflect a similar sense of despair — as a city that is known to be ruthless to its people. Contradicting this despair is the sea, which is known to be a metaphor for the boundless, fluid nature of love, a home to the queer. Mumbai’s own docks and beach fronts hold a lot of queer joy; they have been queer hangout spots for decades.

Despite this, in Kari, we are reminded how daily life in the city can be oppressive and unwelcoming. Kari’s dedication to unclog the sewers of the city — which is both an act of desperation and hope — becomes a silent resistance. A compelling attempt at making her existence known and visible.

Anjali Menon is 24 and spends her time reading, making friends with cats, or loitering in a supermarket. She manages communication and marketing at Champaca Bookstore.

Champaca Bookstore, Café and Library is an independently-owned women-run bookstore and cafe in Bengaluru. The team chooses books with care and tries to include diverse voices and stories, from across time, place, and experience. Instagram: @champacabooks