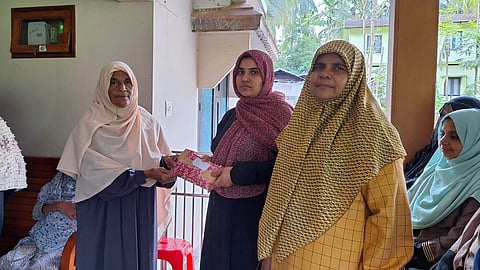

"You always come here to collect contributions from us women, but do not include us in what you do in the mosque," Fathima UT and her friends casually told a few men who came to collect contributions for their mosque. Little did they imagine that their words would trigger a major change. The small village of Santhapuram near Perinthalmanna in Kerala’s Malappuram district became the first to include women in the mosque’s mahallu committee. Fathima was one of the 50 councillors elected to the Santhapuram mahallu committee in 2009, marking a watershed moment in bridging the gap between women and mosques. "And now, the duty of collecting contributions to the mahallu has been allotted to women too," said the 71-year-old, with a laugh.

A mahallu is an area centered around a main mosque where Friday prayers are held, with or without other mosques under its purview. The mahallu system is unique to Kerala, acting as a local unit of social organisation. Mosques are generally managed by various Muslim organisations in the state, and a mahallu can include mosques from the same or different organisations. These mosques play a significant role in the daily lives of Muslim men and women, serving as places for the five daily prayers and Friday prayers and making decisions related to marriage, divorce, inheritance, and more.

Soon after Santhapuram, Othayamangalam and Shivapuram in Kozhikode district also included women in their mahallu committees, followed by a few Jamaat-e-Islami-run mosques in Kannur district. Fifteen years later, in 2024, rough data from the women’s wing of the Jamaat-e-Islami Hind Kerala shows that out of the 600 mosques under its purview, 87 have women in their committees. These committees run and manage the mosques/mahallus and carry out various activities.

The Santhapuram mahallu, run by the Jamaat-e-Islami, covers four wards, spread over three village panchayats. Five women were elected from each of the four wards to the mahallu committee in 2009. However, the women had to wait two more years to get voting rights and become full-fledged councillors and members. In 2011, there were 17 women among a total of 50 councillors, and six of them were elected to the executive committee. Fathima UT was one of them.

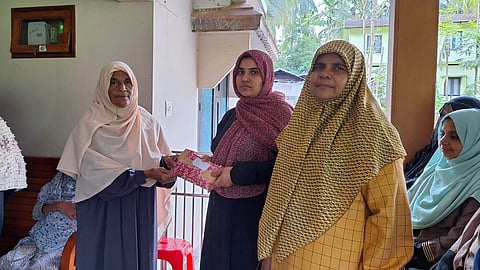

The general activities of the mahallu are carried out under various sub-committees, each focusing on different areas such as education, agriculture, zakat, development, and mediation. While women have been largely excluded from these main sub-committees, they have their own sub-committees that address issues like marriage counselling and self-employment. One significant area where women in the mahallu actively intervene is in assisting with marriages within their community. They address challenges such as poverty and societal standards of beauty by organizing financial aid for weddings, offering pre-and post-marital counselling sessions, and conducting general religious classes on family matters.

The scope of women’s involvement has now increased to helping other women regarding self-employment, education, and so on, to running a physical fitness centre for women, which was established last year in the Shanthapuram mahallu.

“We could provide free food to several affected households in the region, regardless of religion, during the COVID lockdown, when a lot of families were struggling with the loss of jobs,” said 41-year-old Banooja Vadakkuveetil, a member of the Othayamangalam mahallu committee.

There are mosques under the Jamaat-e-Islami, Mujahid groups, and Sunni organisations within the mahallu system. Banooja also mentioned the grand mahallu get-together held last year in Chennamangallur, which was attended by all families in the mahallu. The event featured special programmes targeting various groups, including women, students, and teenagers, covering a wide range of relevant topics.

Many women say that being in the mahal committee has given them acceptance to actively involve in social work.

"If we wish to involve ourselves, we can find ways to do it," said 45-year-old Salva KP, a member of the mahallu committee in Devathiyal, near Calicut University. "We can do social work whether we are part of the mahallu committee or not, but when we are in the committee, we have more power and say," she added.

Since mahallus are the primary units of social organisation in the Muslim community, the participation of women in their committees brings many changes in the general mahallu administration and how they deal with different matters. While 71-year-old Fathima UT considers women's representation in mahallu committees important for addressing gender-specific issues, Banooja sees it as helpful for women in distress to talk openly to fellow women, as they may be hesitant to do so in front of men.

"Mahallus should be representative of the community they stand for, which includes people of different genders, castes, and classes," said Noorjahan K, a research scholar at TISS Mumbai and a social worker focusing on women in mental health distress. Expressing doubt about whether men can fully understand the problems women face within our socio-cultural framework, she pointed to instances where male-dominated mahallu committees had to rely on women like her (outside the committee) to address the issues of women in distress.

Advocate Shajna Mullath (senior panel member of the Kerala High Court Legal Services Authority, Central Govt Standing Counsel and Standing Counsel for High Court of Kerala) said that including women in mosque committees is a positive step towards promoting gender equality and equal participation in religious institutions. She spoke of the diversity of perspectives that women's participation ensures, which could lead to more inclusive decision-making processes and policies that reflect the entire community’s concerns. She also added that it serves as a positive example for younger generations, encouraging them to actively engage in their religious communities and pursue leadership roles.

However, though the process of inclusion of women in mahallu committees began way back in 2009, only less than 100 mahallus have joined the list even after 15 years. And in most of those mahallus where women have a presence, they only deal with ‘typical ladies’ topics’ such as family and marriage. The women are still unable to involve creatively even in these issues, and a senior member of a mahallu in Kozhikode shared that “men have been dealing with mediations in family problems for years, and are experienced in it, so women only help them when asked”.

“Soon after the KNM passed the resolution demanding women representation in mosque committees back in 2015, I had written in an article that the loose term of representation should be better clarified - as to how and where all women would have representation. If that is not clearly demarcated, women's space in mosque committees also would be just like anywhere else,” said Noorjahan.

Another factor that she pointed out is about the women who become members. “We should consider how these women committee members handle topics like marriage. If their approach is to pressurise the younger generation to stay in difficult marriages, they become protectors of patriarchy themselves. Women in the mahallu committees should negotiate space and gender rights,” she added.

Fathima, who has been a member of the mahallu committee for 15 years now, said that women should not give up, even if the work and responsibilities involved in being part of the committees may seem like an uphill battle at the moment. “More young and educated women should come up, and they should be given due attention too. Only then can more changes be brought in,” she pointed out.

Islam came to Kerala in the 8th century AD through Arab traders, some of whom married them and settled in Kerala. They initially built around ten mosques along the coastal regions, the first of which is said to be the Cheraman Mosque at Kodungallur. As the Muslim population grew, more mosques were built.

Like women’s movements globally, the entry of women to mosques came up as a topic in the Muslim public sphere in Kerala in the 20th century, and the Kerala Muslim Aikya Sangham, an organisation of Muslim scholars, was the first to demand reformation in the Muslim community in the 1920s, including the need to make women literate. This created a difference of opinion among the more conservative groups in the community, and they branched out, forming the Samastha Kerala Jamiyyathul Ulama within a few years. Thereafter, public debates between the two organisations became a common occurrence in Kerala.

The topic of women’s entry to mosques came up in the 1930s, and it was in 1946 that women first attended the Friday prayers at a mosque in the village of Othayi in Malappuram. The formation of the Kerala Nadvathul Mujahideen- a socio-religious organisation- in 1950 added traction to the demand for women’s entry to mosques. Once the mujahid organisations and the Jamaat-e-Islami began building their own mosques, they allocated separate spaces for women.

The traditional Sunni organisations—Samastha Kerala Jamiyyathul Ulama, All India Jamiyathul Ulema (commonly known as AP Samastha or Kanthapuram Samastha), and the Dakshina Kerala Jamiyyathul Ulama—still do not allow women to enter their mosques. Recently, however, they have started arranging a separate room inside or near the mosque complex for "women who are travelling." This means that local women residents are still not permitted to enter these mosques and are expected to offer namaz in their own homes. While travelling women are allowed to offer namaz, they cannot do so in congregation with the men in the mosque.

In 2015, the Mujahid/Salafi organisation KNM Markazu Da’wa passed a resolution demanding women to be included in mosque committees, but only a few mosques followed it.

In 2020, the Masjid Council Kerala, which deals with more than 600 mosques under the Jamaat-e Islami, instructed the mosques and mahallus under its purview to include women in their committees, though at least a few had already begun the process years back. However, neither organisations have the exact number of masjids/mahallus with women participation in committees.

However, Abdussamad Pookkottur, working secretary of the Sunni mahallu Federation claims that men in the committees are protecting the rights of women, “The mosques/mahallus under Samastha are managed by a committee formed by men, as is traditionally practiced, and women are not included in these committees. However, their rights are never violated. If women have any issues to be raised, they have the right to approach the mosque committee. Their complaints will be dealt with respectfully.”

The Federation is in charge of more than 3,000 mahallus spanning more than 6,000 mosques all over the state under the Samastha Kerala Jamiyyathul Ulama, the Muslim organisation with the largest number of followers in Kerala.

Najiya O is a freelance journalist based in Kerala, focusing on positive stories and tales about women and the marginalised.