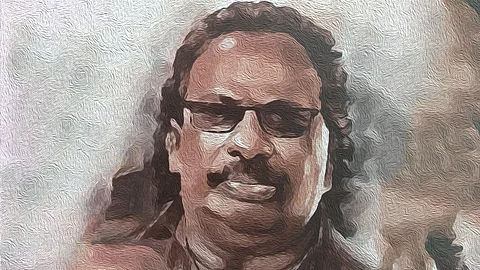

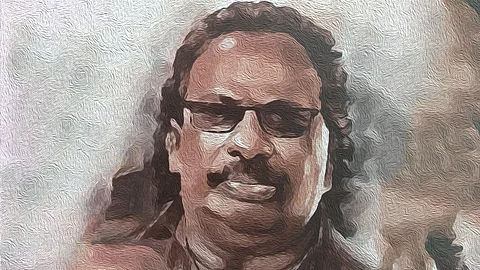

Recently there were reports in the media based on the data tabled in the Parliament regarding the dropout of students from backward and SC/ST communities from the IITs/IIMs and Central Universities. It did not shock anyone as everyone knew this was the reality of the famed higher educational institutions in India. This report came a couple of days after the shocking news of the suicide of Prof M Kunhaman, Dalit scholar and economist from Kerala. He took his life on Sunday, December 3. It was his 74th birthday.

M Kunhaman, was born into Panan (SC) community in Vandanamkurissi village of Palakkad. A doctorate holder in economics from the Cochin University of Science and Technology (Cusat) he taught at the Kerala University in Thiruvananthapuram and at Tuljapur campus of Tata Institute of Social Sciences (TISS). He had won first rank in MA Economics and was the second Dalit student after KR Narayanan, to win a rank at the postgraduate level.

At an individual level, Kunhaman throughout his life had fought this higher education system overrun by caste. This was also one of the major themes that he repeatedly brought to the attention through his writings. But this grievous issue of students from backward and SC/ST communities was never attended to by any policy makers.

Kunhaman would have been the right person to set a policy on making preeminent higher educational institutions hospitable to marginalised communities. No political parties or governments ever invited him to policy making institutions and lead academic institutions. Being a renowned economist, academic, Dalit thinker and social visionary, Kunhaman was ideally suited for such important decision making positions. Though a critic of the system and an articulate dissenter, he would not have shied away from taking up such responsibilities. But alas! our political parties only need sycophants and they could hardly accommodate critical voices.

Kunhaman's death was shocking and his loss immeasurable. Everyone who has read him would acknowledge this. Why was it shocking? Kunhaman was actively contributing to the dissenting discourse of the times with his sharp intellectual analysis and incisive take on the establishments. His loss is immeasurable because critical dissent is becoming a rare phenomena in the intellectual culture where servility to the cults of political personalities in power and consumerist-populism has become the mainstay in the idea-market. In times of intellectual deceit, Kunhaman's voice articulated the honest and dissenting conscience of our times.

When propagandist social science and academic deceit is colonising the thinking process, dissent is synonymous with intellectual honesty. Kunhaman's dissent and non-conformism to the stereotypical market-oriented thinking is emblematic of his intellectual honesty. The rise of Hindutva also has opened market opportunities for any average intellectuals and social scientists to manipulate and adjust with the powers – the Right and compromised Left – who are assured with pelf and market fame. Kunhaman was never enamoured by any of these. His reluctance to cage himself to any ideology, organisation and any established agency is an outcome of his intellectual non-conformism that can be aptly called defiance.

Kunhaman wanted to name the English translation of his quasi-memoir—Defiance. The original title of his quasi memoir is "Ethiru'' in Malayalam. Defiance captures the essence of affirmative anti-establishment rigour of his thought. Independent intellectuals are a rare phenomena in Kerala's intellectual culture. To become independent, the first thing is to break with the underlying epistemic caste structures. The intelligentsia's dependency on organisations and establishment perhaps owe to the legacy of the comforts that caste has provided as a back-end mechanism for the intellectuals. Organisations, like caste, provide security, visibility and back-end support. In a superfluous manner, the dependent intellectuals may have objected to hierarchical structures but deep down they pattern their idea of intellectual life rigorously on hierarchical terms. Kunhaman, being a truly independent intellectual, was averse to this idea of hierarchical structures right from the time he took to serious academics. His most quoted conversation between Kunhaman and the renowned economist and institution builder Prof KN Raj, who was his guide, exemplifies this.

Recording this exchange, Kunhaman says in his quasi-memoir, "Ethiru", that he regularly questioned Raj by saying that the economics they teach does not correspond to the realities of the depressed class. Only when people from the oppressed sections of the society start to occupy the domains of knowledge then only it will start reflecting their reality. Raj responded to this in a conversation after Kunhaman completed his doctoral dissertation by saying that he was questioning the hierarchy. To which Kunhaman, as quoted in his memoir, responds firmly and assertively:

"Don't talk from such heights. Practically you all are big people. Nevertheless, you are obliged by the Constitution. We are opposed to the established society. We make sure that this is expressed at the right opportunities without thinking what the consequences would be. You are the son of a judge in the British period. You grew up in such an enabling condition whereas we grew begging for food and met with the violence of yours against us. Therefore, I am antagonistic to you. I have to express it and I consider it as my moral obligation. If you don't like it, just say Ok. If you were in my place you would not have even passed the school finals and if I were in your position, I would have received a Nobel prize. This difference actually exists between us."

Kunhaman then says if any situation demanded an expression of dissent he would have not hesitated to express it. He also narrates an event where he expressed his dissent to Dr KR Narayanan, who was then the Vice President of India, on an important policy like the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) and for which he was man-handled by some in the audience. There is much to read in his reply to KN Raj. On an individual level Kunhaman was keenly aware of his brilliance as he knew he was there in that venerated institution sitting in front of the celebrated economist only because he had secured first rank for his MA in Economics.

At the sametime, it was not an ego-centric response because he was only expressing the antagonism that the oppressed felt at the heart against the oppressive casteist structures of institutions. Anyone who knew Kunhaman would acknowledge the fact that he was not an ego-centric personality and those who have met him must surely have felt his jovial and friendly engagement with zero botherations on any existing rules of hierarchy. As a student of development communication at C-DIT, I was introduced to Kunhaman's sessions on development economics. None of us ever felt in his class the hierarchical distance between students and the teacher. He invited us to dissent. The ego-centricity, the display of academic class and intellect is an outcome of priestly consciousness arising out of their own petty upper-casteism. Kunhaman self-exiled himself from that "guru varnashrama".

It was really unfortunate that his memoir, a compilation of a series of conversations with journalist K Kannan, was celebrated only for the first few chapters where he narrates the caste oppressions that he had to encounter in younger days. A restricted reading of the first few chapters only intended to reduce the intellectual personality of Kunhaman to fit some Kerala model caste-renaissance narrative. In fact the first few chapters where he talks about his personal struggles with the oppressive landlordism was only to show the Savarnas the immorality of their social system. Indeed, in the chapters after the first few, he converses about his critique of Marxism, academic institutions and conventions of political economy.

He talks in detail about the changing tastes and orientation of the younger generation. One theme that I think that was close to him in the later period of his intellectual life was about the unequal wealth distribution and why accumulation of capital becomes important for Dalit progress. Kunhaman was never averse to making controversial remarks. He made critical observations on the emergent conflict between Dalit population and Backward communities. He wrote in detail about the newly emergent class called the precariat, a social class who do not have secure employment or jobs. He was well-versed with the post-Marxist development critiques.

Deeper into his personal narrative, one can sense the deep-felt anger of a community betrayed by the political class. Also, he expressed anguish and helplessness in the way political parties have manipulated the politics of the oppressed. Hardly agreeable this may be, yet Kunhaman vehemently argued that the "marginalised society should understand that they should not see the benefits arising out of the historical oppression as birth rights. It is the time for living with a competitive spirit and approaching issues intellectually. The marginalised should not be seeking benefits. Even if political parties give it to them they should not accept it. With a competitive spirit they have grown intellectually. What they need is entrepreneurship and property rights".

Kunhaman's was a unique Dalit voice and he articulated a different vision on which one can disagree a lot. He never intended anyone to agree with him as well. The radical and independent mind of Kunhaman resisted casting him into any stereotype. A friend of mine chided the reports that termed Kunhaman as a Dalit thinker. His criticism was that Dalit is a caste-marker and it should not be attributed to a preeminent thinker like Kunhaman. I objected to his observation. Dalit is as much or even more than prefixing an intellectual with Marxist, Gandhian, Ambedkarite or Feminist honorifics. Dalit is not a caste-marker in this respect. It represents the philosophy of social emancipation. Hence, Kunhaman is aptly a Dalit thinker.

However, makers of stereotypes wanted to caste-mark Kunhaman in their own caste-mould suited to their own established conventions. Kunhaman's life in the world of ideas, intellectual personality and his scholarly contributions resists any such caste-marking. He chose to disaffiliate with any pre-set ideas and organisational practices. When you think of Kunhaman you think of Black writer James Baldwin. There are many similarities between them. Kunhaman also reminds you of the title of the film Raoul Peck made on James Baldwin "I am not your Negro". So was the fiercely fearless radical independence asserted by Kunhaman that he always meant to say "I am not your Dalit."

(Damodar Prasad is an independent media researcher and bilingual writer)