Follow TNM’s WhatsApp channel for news updates and story links.

The Karnataka government is considering introducing elections to student unions in colleges and universities, a move that has found support across political parties. The proposal comes three decades after student elections disappeared from campuses, during which time higher education in the state has been transformed.

Most students now study in private institutions where administrators exercise near-total control and student representation is minimal or absent.

In December 2025, the Karnataka Pradesh Congress Committee (KPCC) president, DK Shivakumar, announced that a nine-member panel of senior party leaders headed by Medical Education Minister Sharan Prakash Patil would examine whether or not student union elections could be brought back.

The state government first banned elections for recognised student unions in the 1989–90 academic year. Elections were briefly allowed to resume and then discontinued permanently in 1997–98.

After the ban, students could still organise themselves and, in some cases, hold elections on campus, but these bodies were not officially registered and had no formal role in university governance.

But before the ban, elected student representatives sat on the Senate, a statutory decision-making body in public universities.

As per the Karnataka State Universities Act (2000), students nominated by the university management can be part of governing bodies of campuses. Overnight, campus leaders went from being representatives of the student body to being representatives of the management. If the system in state universities is undemocratic, the laws governing private universities in Karnataka do not mandate student representation in statutory bodies at all.

The Congress panel was formed six months after Karnataka Congress leaders, including Chief Minister Siddaramaiah and Shivakumar, began dropping hints, saying that student elections were crucial to developing political consciousness and leadership among young people.

Both the Chief Minister and his Deputy, and many members of the panel, such as MLC Puttanna, MLA Rizwan Arshad, and MLC Saleem Ahmed, started their political careers as student leaders.

Political reactions

Shivakumar’s announcement has elicited a rare consensus among Karnataka’s three major political parties. Leaders of the Congress, the Bharatiya Janata party (BJP) and the Janata Dal (Secular) have all said that they are in favour of reinstating elections to student unions in universities and colleges.

Rizwan Arshad, who represents the Shivajinagar assembly constituency in Bengaluru, told TNM, “The majority of our population is young and studying. They need to be aware of the democratic process. Campus elections will strengthen democracy in colleges and universities and will help identify new leadership for the future.”

BJP MLC N Ravikumar, who spent 25 years as a full-time activist of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh’s (RSS) student wing Akhila Bharatiya Vidyarthi Parishad (ABVP), welcomed the move but was cautious. “It’s certainly good to have student elections, but they should be non-political. Let the Congress panel’s report come, and then the party will respond.”

Janata Dal (Secular) leader Nikhil Kumaraswamy has also welcomed the move to reintroduce student elections.

While all politicians who spoke to TNM were wary of a return to lawlessness on campuses, activists say that the 1990s’ ban on student elections must also be seen in the larger political context of the previous two decades.

The 1970s saw the emergence of Marxist, socialist and anti-caste student movements which increasingly challenged the Congress’ dominance on Karnataka campuses over the next decade. This challenge was systematically dismantled from the 1980s onwards through an education policy that promoted privatisation and commercialisation of education.

Why student elections were banned

Political involvement and violence on campus were an undeniable reality and still exist in varying degrees. The Lyngdoh Committee, too, recorded alarming violence on campuses in its 2006 report submitted to the Supreme Court.

The Lyngdoh Committee was formed in 2005 to scrutinise student elections after a dispute between private colleges in Kerala and the University of Kerala reached the Supreme Court.

The committee held public meetings in Kolkata, New Delhi, Mumbai, Lucknow and Chennai, which were attended by representatives from state-run and private universities and student organisations. It also sought the views of over 300 students, teachers, colleges and universities through a questionnaire on the election process, campus violence, election expenditure, acceptable methods of canvassing, criminalisation, etc. and submitted its report in 2006.

The committee’s recommendations form the basis of elections in universities such as Jawaharlal Nehru University and the University of Hyderabad. In fact, the Committee noted that the election processes in these two universities were worth emulating.

“All the undesirable elements that you saw in the general elections back then were present in student politics too,” recalled Indudhara Honnapura, a Bengaluru-based senior journalist. Rival groups attacked each other, candidates were forced to withdraw from elections, and students were plied with liquor, he said.

According to TH Murthy, who was a postgraduate student at Bangalore University (BU) in 1985-87, Congress-backed violence reached extreme levels during D Devaraj Urs’s tenures as chief minister from 1972 to 1977, and from 1978 to 1980.

“Devaraj Urs congratulated the office bearers during his tenure. Violence reduced somewhat by the time Ramakrishna Hegde became the chief minister in 1983.”

A chief minister congratulating elected student representatives indicates political investment in student elections. For example, New Delhi Chief Minister Rekha Gupta congratulating the Akhil Bharatiya Vidyarthi Parishat (ABVP) candidates who won three posts in the Delhi University Students' Union elections in September last year raised eyebrows.

Challenging Congress’ power

Indudhara pointed out that the ban must also be seen in the context of challenges to the Congress’ hegemony from socialist and Dalit groups. “The NSUI was strong. They attacked socialist and left-wing student groups,” he alleged.

By the 1990s, students affiliated with socialist, communist and Dalit groups were seriously challenging the Congress’ dominance on college and university campuses in Bengaluru, Hubballi, Dharwad and other prominent educational centres. At the time the ABVP had a negligible presence.

Murthy said that the Dalit Vidyarthi Okkoota, or the Dalit Students’ Federation (DSF), was formed in 1974 as the student wing of the Dalit Sangharsh Samiti (DSS), which was launched the previous year.

DSF students campaigned for measures that directly affected education, such as an increase in scholarship funds. They even pressured the state government to provide fee concessions for Scheduled Caste (SC) and Scheduled Tribe (ST) students in private colleges.

But the DSF also had a broader political vision that included creating awareness about the Constitution and building solidarities with backward classes groups over affirmative action.

The DSF organised a two-day seminar in Bengaluru on the importance of reservations for BC students and invited a retired Supreme Court judge to speak on the subject. After the Havanur Commission recommended reservations in employment and education for BC students, Suddi Sangati, a weekly, published a full list of castes eligible for reservations. DSF members distributed copies in buses in Bengaluru, Murthy recalled.

The 1980s saw the CPI(M)-backed Students Federation of India (SFI) band together with the DSF on several issues. “The political agenda of the Left and DSF was similar, so we often worked together,” Murthy said.

One such issue that the two groups took up together was the protests against the National Policy on Education introduced by Rajiv Gandhi in 1986.

CPI(M) state secretary K Prakash, also an alumnus of BU, told TNM that the DSF, SFI and other groups organised day-long shutdowns of the Bangalore University campus in protest.

“Rajiv Gandhi’s new education policy created the base for many of the elements you see in the New Education Policy (NEP) 2020,” Prakash said. These included increasing the number of centres of excellence, autonomous colleges, and deemed universities.

The last straw for the government, according to Murthy, were the pro-Mandal protests.

Murthy said that when the VP Singh-led Union government was in the process of implementing the Mandal Commission report in 1989-90, Karnataka’s then higher education minister KH Ranganath had remarked that reservations for BC students in higher education were unnecessary. Strong protests from students forced him to resign.

“I was among those who submitted a memorandum to Rajiv Gandhi at the gate of Bangalore University when he was on his way to Mysuru. They banned elections in 1990 because there were strong protests demanding reservation for OBCs, and they had to contain that,” Murthy said.

Privatisation and commercialisation

KS Lakshmi, state vice president of All India Democratic Women’s Association (AIDWA), won as joint secretary of the Jnanabharthi Students Association (JBSA), the official union of BU, in the 1994-95 academic year.

“I was the first woman to win the election to that post,” she said, adding that she was also elected to the Senate for a year.

Until 2000, public universities had student unions and a Senate that included elected graduates. This system built student opinion into policymaking.

Lakshmi believes that the Union government’s push to privatise and commercialise education also played a role in the Karnataka government’s decision to ban student elections and get rid of the Senate.

Until the Karnataka State Universities Act 1976 was replaced by the 2000 Act, public universities had a body called the Senate. Among its 50-plus members were graduates—elected by other graduates, as well as five elected student representatives and three students nominated by the Chancellor.

The 1976 Act specified how university graduates could elect other university graduates as Senate members.

For example, any graduate living in the four districts covered by Bangalore University for at least two years could register on the electoral rolls of BU and also contest Senate elections. Graduates in law and commerce would respectively elect one representative each, while the other faculties together would elect three representatives. All the graduates together elected a woman graduate to the Senate.

“Because of Rajiv Gandhi’s 1986 education policy, the government cut back on funding. Naturally, there were protests. Education was once a fundamental responsibility of the government. But they began to reduce resources and abdicated that responsibility,” she added.

To compensate, they began to introduce self-financing courses and paid seats, Lakshmi noted. “In order to implement all this, they needed an atmosphere in which nobody would be able to question them. So they dismantled elected bodies by amending the universities act.”

The 2000 Act removed the Senate and introduced a provision for the vice chancellor to nominate six students to the Academic Council.

“The current practice is that vice chancellors choose students who won’t utter a word during meetings,” said Muralidhar BL, Professor and president of the Bangalore University Teachers’ Council.

In contrast, the individual laws regulating private universities in Karnataka do not mandate the appointment of students to the Academic Council. They only list a handful of officials, such as the vice chancellor as members, and grant the university the discretion to appoint other persons of its choice.

An advocate of reintroducing student elections, Muralidhara added that if student elections are revived, the relevant laws should also be amended to ensure that elected students are part of the Academic Council where they can have a say in policy.

Pushback from private universities?

In the decades after the ban, private institutions have overtaken the state as the major education providers.

According to the All India Survey on Higher Education (AISHE) 2021-22, over 2.95 crore students* across India get their degrees from private colleges affiliated with public universities in different states.

In contrast, the number of students in state government-run universities is just 29 lakh. The number of students in private universities, including aided private deemed universities, is around 25 lakh.

In Karnataka, just over five lakh students go to 704 state-run colleges while over 12 lakh study in 3,579 private aided and unaided colleges.

That private educational institutions were reluctant to allow student representation was even pointed out by the Lyngdoh Committee. The committee reported that southern states had a relatively larger number of privately run institutions, many of which, it noted with alarm, were run by politicians.

In its recommendations, the Lyngdoh Committee called for elections to student unions to be made mandatory across India. It said that if student elections could not be held immediately after the recommendations were accepted, institutions could nominate members to student unions as a temporary measure and switch to conducting elections within five years.

Congress leaders privately acknowledge that the private education sector is a powerful lobby which has already begun to exert pressure against student elections.

An MLC who spoke to TNM said that heads of private institutions have begun making a beeline to meet Congress chief DK Shivakumar to raise objections over student elections.

BV Srinivas, All India Congress Committee (AICC) national secretary and a former national president of the Youth Congress, dismissed these concerns.

“Even if politicians are running educational institutions, students must be given a chance to understand their problems. Creating the opportunity for that is good. Our leader (DK Shivakumar) runs institutions but he himself is saying student elections are important,” he said.

Shivakumar has been running his own chain of educational institutions for the past 24 years through the DKS Charitable Trust, of which he is chairman.

Shivajinagar MLA Rizwan Arshad acknowledged that private institutions, many of which are run by politicians, would likely resist introducing student elections.

“Whether institutions are owned by politicians or anyone else, the government’s decision will be applicable to all. Most private institutions will not want elections because they want complete control (over students and the institutions they run). There is so much that students can learn through elections. If a decision is made in favour of elections, private colleges will not be exempted,” Rizwan Arshad said.

A member of the panel who spoke to TNM on the condition of anonymity said, “Some members are suggesting that we implement elections in government institutions first and then introduce them in private colleges. But I am in favour of implementing elections in all institutions without exemption.”

However, a statement made by MLA Saleem Ahmed six months before the panel was formed may indicate where the state government stands. In July last year Saleem Ahmed, once a student leader himself, said that elections might be implemented in government colleges first.

Despite ban, student politics is still alive

Despite the ban on student union elections, student activism hasn’t died out completely. In some public universities, student welfare groups have risen out of the institutions’ long political tradition, while government colleges and private colleges and universities see sporadic attempts by students to fight back against authoritarian administrations.

At BU, the Postgraduate Students and Research Scholars Association campaigns on behalf of students with indirect support from the Bangalore University Teachers’ Council (BUTC), a teachers’ union, said Chandru Periyar, president of the student association.

“When issues arise, we informally get them resolved. The teachers support us if they think our demands are valid. Similar informal unions exist in a handful of other government-run universities. We all keep in touch with each other,” Chandru added.

Mysore University too has an association of postgraduate students and research scholars, which grew out of the DSF about 12 years ago. Its former president, Mahesh Sosale, told TNM that research scholars and PG students have been running an informally elected students’ union.

“The convention is that only a second-year PG student can contest for a post. Voting took place by a show of hands. Four years ago, someone objected to this process because it was not a secret vote. Since then we’ve been conducting elections with ballot papers,” Mahesh said.

The groups at both universities have had some measure of success. For instance, during the COVID-19 lockdown, Mahesh led a campaign through online meetings and forced the university to release scholarship funds. “Government employees received their salaries while they were at home. Why shouldn’t we have been given our scholarships?” he asked.

Students in both government and private colleges too have made attempts to get their concerns addressed by the administration, says Aratrika Dey, a final-year PhD student and Bengaluru general secretary of the All India Students Association (AISA).

Last year, students at a private university in Bengaluru protested against an increase in campus meal prices and a reduction in food quantity. In response, the university increased the quantity, but the price was only marginally reduced.

“We see these partial victories here and there even in the absence of student unions. But this becomes possible only when students come together. What becomes really important from our end is to give them moral support because they’re really scared of the management,” Aratrika said.

Students think they will be intentionally failed in their exams, or denied attendance, hall tickets, or degree certificates, she said. “Different kinds of intimidation tactics are used by colleges, both private and government.”

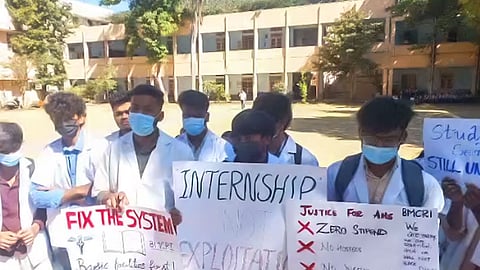

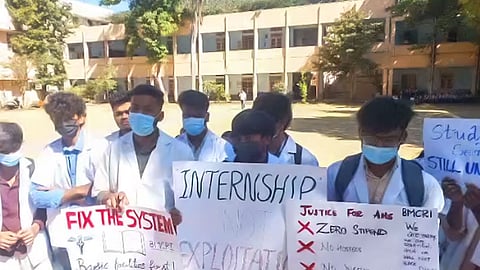

Recently, students of allied health sciences at the state-run Bangalore Medical College and Research Institute (BMCRI) alleged that they were facing intimidation from college authorities for demanding internship stipends.

Aratrika agreed that students in many private colleges tend to be disinterested in politics and are more orientated towards finding jobs. She added that their problems, such as extra workload, moral policing or exorbitant fees, “cannot be solved by money”.

She cited the example of students at a private dental college in Bengaluru which charges lakhs of rupees in fees. Some students had reached out to AISA for help with their stipends.

“Students may not see the immediate connection between their problems and the privatisation of education. But they also realise that it’s possible to resolve issues when there’s some kind of unity, when students collectively speak out against management,” Aratrika further said.

Lakshmi pointed out that such groups can only exert pressure. “They can’t fight against policy from the inside.” She added that student unions derived both their legitimacy and power from being elected directly by the students, which university authorities could not dismiss.

In the past, when universities tried to introduce policies that could adversely affect students, student representatives and elected graduates could and did boycott or adjourn Senate meetings.

“We could even reverse decisions. It’s not necessary that government appointees always side with the authorities. Many times, they supported us. If elected bodies exist, they will fight back,” Lakshmi further said.

Future of student leaders

Although politicians of all parties have been extolling the virtues of student elections on the development of political consciousness among young people, public universities have increasingly become ghettoised. Private universities have priced out all but the richest students and have turned into neo-agraharams.

SC, ST, BC and minorities form 58% of the student strength in public universities, but that figure drops to 43% in private universities, AISHE’s all-India data shows.

On the other hand, private colleges which are affiliated with public universities reflect society’s demography more closely—SC, ST, BC and minority students form 70% of the student strength.

“A lot of serious intellectual discussions, reading and writing happen at public universities. Private universities lack this vibrant space. They’re just preparing students for a job-orientated market. Students there don’t raise critical questions about how one can contribute to society or critical thinking, social progress or the country’s progress,” Bhanuprakash, Assistant Professor of Political Science at St Joseph’s University, said.

Bhanuprakash, who studied at University of Hyderabad, said that university elections contributed to students’ political awareness. “Candidates’ views are questioned in a public forum attended by the entire student body. Anyone could ask questions.”

Many students from marginalised backgrounds in public universities are first-generation learners, pointed out Bhanuprakash. This puts great pressure on them, unlike what other students face, he added.

“They have something to prove to society and to their families while maintaining academic standards. With all this in the balance, they struggle with the dilemma of whether or not to participate in campus politics and how they should manage their academics. This is a great conflict for these students,” Bhanuprakash further said.

He also highlighted how both universities and student groups affiliated with political parties do not help marginalised students with their struggles, especially the struggle against casteist discrimination by professors and students.

It is Ambedkarite, Phuleite, Bahujan, Periyarist and tribal student groups unaffiliated with any political party which provide the support system that students from these backgrounds need, Bhanuprakash said, adding that such groups also offer mentorship for academics and careers.

Despite such immense pressure, students from marginalised communities in public universities have brought about one of the greatest shifts in India’s political imagination in the past decade. Rohith Vemula’s institutional murder in January 2016 and the students who rallied around his death made caste and casteism an issue that could no longer be ignored—by either a caste-blind or caste-adhering public and the political class.

If the Congress exempts the private sector from holding student elections, Bhanuprakash believes that the political class’ expectations—that student elections would foster political awareness and drive social change—would fall on the poorest students from marginalised communities.

His fears are not unwarranted.

The decade since Rohith’s death has made it evident that there are few takers among mainstream political parties for politically articulate students from marginalised communities.

Bhanuprakash pointed out that political parties absorb students from their student wings. Kanhaiya Kumar, of the Bhumihar Brahmin caste, won the election to the post of president of the JNU student union in 2016. He was backed by the Communist Party of India (CPI) and eventually joined the Congress.

“But what happens to students who identify with the ideologies of Babasaheb Ambedkar, Savitribai Phule, or Periyar? Even if these students have a critical understanding of political and social issues, their recruitment to mainstream politics remains negligible. They’re deserted,” he added.

The Congress party in Karnataka will have to reckon with these questions as it proclaims its commitment to social justice by setting up a panel on student elections and promising a law named after Rohith Vemula to tackle caste-based discrimination on campuses.

January 17, 2026, was the 10th anniversary of Rohit Vemula’s death. For most part of the last decade, during which the BRS was in power, the state government and police took an openly hostile position against the campaigners seeking justice for Rohith. But things did not improve even after the Congress came to power two years ago. The police cases against students haven't been withdrawn by the state government yet. There has been no progress either in the investigation into the death of Rohith.

May 2026 will be the second anniversary of the Congress party’s failure to ensure accountability for his institutional murder in a state where it has now been in power for about two years.

*This figure also includes students of constituent colleges of state universities, which form a small number. For instance, BU has four constituent colleges and nearly 300 affiliated private colleges.