This piece is a part of TNM's reader-funded Cooperative Federalism Project. Indian residents can support the project here, and NRIs, please click here.

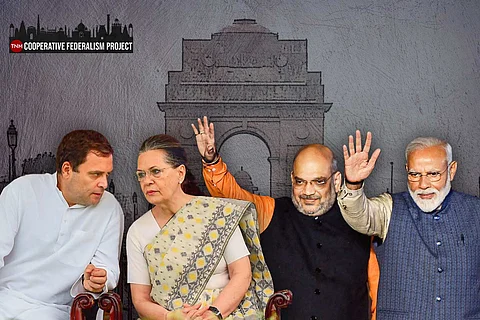

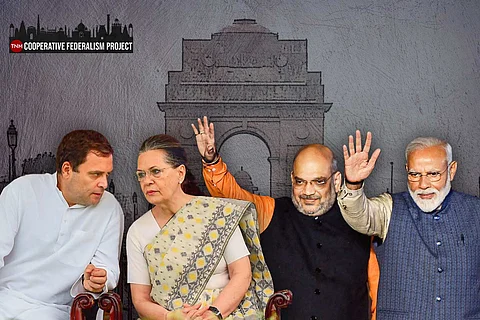

Centralisation of power is federalism’s arch nemesis. While India’s founding fathers designed a quasi-federal structure for the country, the high command culture, particularly in national parties, has further consolidated power in the hands of a few – a few who in fact are not directly involved in the governance of states. The high command culture has been in existence for decades in both the Congress and BJP, and has come to be accepted as the norm, without much heed being paid to how this works against the interest of the states.

High command is a power structure in a political party, and usually refers to a small group of people or even members of a single family, who dictate all the decisions taken. So irrespective of what position a party member holds in either the state or Union government, the will of the high command will be supreme. So the high command, by default, becomes the unelected, extra-Constitutional power, undermining the autonomy of elected representatives.

The Congress party can be credited (read: blamed) for pioneering this practice as early as the late 1960s. Indira Gandhi controlled the party with a firm hand and systematically weakened the state representatives. The party image is largely centered around the high command, reducing others to the role of props. This continued for decades to come, only weakening post 2010.

The BJP, which had been a cadre-based party in the beginning, with decisions often taken with the consent of a group of senior leaders along with the RSS, changed its style of functioning post 2014. In the Modi-Shah era, not only did the party adopt an Indira-style of high command, but took it up a notch.

Karnataka has a long history of party high commands interfering with governance of the state, several times even against the interest of the state and its people. For many decades, the Chief Ministers of the state have been appointed by the party high command in Delhi rather than the legislators in Karnataka. And if the CM loses the favour of the high command, then he has been unceremoniously replaced. In 1990, Congress (I) under Rajiv Gandhi ousted Veerendra Patil as the CM and imposed President’s rule in the state in a bid to show who is in command. This cost the party the support of one of the most influential vote banks in the state — the Lingayats.

The BJP too used similar tactics. When Yediyurappa as the CM became untenable for the BJP central leadership, he was forced to step down in 2011. Ten years later, history repeated itself in 2021 when a defiant Yediyurappa was asked to make way for Basavaraj Bommai.

Even Karnataka’s only significant regional party, JD(S), has seen interference from the high command (the Gowda family) in the appointment of Chief Ministers. When Deve Gowda was the Prime Minister, he is said to have asked the then-Karnataka CM JH Patel to step down to make way for another senior leader. After all attempts to convince him failed, Deve Gowda had reportedly come down to Bengaluru to meet Patel in person and convince him to resign. But Patel’s defiance continued.

The high command’s highhandedness is not limited to the appointment of the CM but is extended to even the choice of his Cabinet. During Siddaramaiah’s tenure as the CM between 2013 and 2018, while a weakened high command abstained from close interference in choosing his Cabinet, Siddaramaiah was forced to drop a minister despite voicing his strong dissent. His Cabinet colleague KJ George was named along with three other police officers in an FIR filed by the CBI in the suicide case of MK Ganapathy, a former police officer. While Siddaramaiah had continued to defend George despite the opposition’s onslaught, the Congress high command is said to have intervened and directed Siddaramaiah to drop George from the Cabinet. In this example, though the high command may have been right in its stance, there are many examples where well performing ministers have been asked to go.

Yediyurappa has had to endure the shadow of central leadership throughout his tenure as CM – from curating his Cabinet to clipping his wings. In 2008, at the high command’s behest, he was forced to include the Reddy brothers and their aides ministers, much to his angst. In 2019, Yediyurappa had to wait for almost a month to get a Cabinet, with his party senior leadership — Narendra Modi and Amit Shah — busy with developments following the abrogation of Article 370 in Jammu and Kashmir. Despite several visits to New Delhi, his efforts to get an appointment with PM Modi and Amit Shah to discuss the Cabinet was futile.

And when he finally did get a Cabinet, he was as much in the dark as the rest of the state over who his colleagues were, until a few hours before the swearing-in ceremony, with the approved list of ministers being sent at the last minute causing Yediyurappa much embarrassment. In the next two years as CM, each time he wanted to expand or reshuffle his Cabinet, Yediyurappa had to wait endlessly for the high command to clear the decision.

A stable and autonomous Chief Minister, functioning free from the diktats of the central leadership, is imperative for the administration of a state.

In matters of policy too, the stamp of the high command has been evident on state administration. While Siddaramiah had a relatively free reign as CM, given that it was at a time when the Congress was on a downward slope in the country, there have been several instances where the will of the Delhi leadership prevailed.

In 2016, Siddaramaiah advocated for a strong law to curb superstitious practices in the state and mooted the ‘Karnataka Prevention and Eradication of Human Sacrifice and Other Inhuman Evil and Aghori Practices and Black Magic Bill’ – a pet project. While the Bill faced stiff opposition from many within the state Congress too, the central leadership reportedly intervened and asked Siddaramaiah to put it on hold. Congress leaders were worried that the party would lose support from religious groups. Eventually, under pressure from all quarters, the Bill had to be diluted.

One of the hallmarks of the high command culture is attribution of credit for all success in administration to one or two leaders in the party. This invariably does not apply to failures which is the collective burden. The Congress party, for long, has applied this in projecting the members of the Gandhi family as saviours. In late 2017, when the Karnataka government planned to open canteens that provide subsidised meals across Bengaluru, the initial plan was to name them after any legendary icon from Karnataka. The party high command, however, reportedly insisted on naming the scheme after the former Prime Minister, Indira Gandhi. Eventually, the high command’s will prevailed.

When the Karnataka government sent a proposal to the Union government requesting that the approved design of the Karnataka flag be included in the schedule of the Emblems and Names (Prevention of Misuse) Act, 1950, according it the status of an official flag, a senior leader close to the Gandhis called Siddaramiah and expressed his objection in the strongest terms, sources in the former CM’s office told TNM. The senior leader reportedly told Siddaramiah that as a CM from a national party like Congress, he should not push for such moves that can be seen as ‘secessionist’ and can damage the party.

One of the most controversial decisions of the Siddaramaiah government was the recommendation of a separate religion status to Lingayats. This decision had even the state unit split with some pushing for the move and a few others strongly opposing it, calling it political suicide. At this juncture, certain central leaders of the Congress are said to have asked Siddaramaiah to drop the idea, worried that it will have a ripple effect.

When the 2018 Assembly elections ended in a hung Assembly, the Congress high command decided to ally with the JD(S) to form the government. This move was strongly opposed by several state leaders, including the sitting CM Siddaramaiah, under whose name the Congress had fought the elections. But the decision of the high command prevailed and an alliance was struck with the JD(S) to form a coalition government.

When Yediyurappa became CM in 2019, it was apparent from day one that he would function with limited freedom to make decisions, with the high command dictating the governance from Delhi. The feisty Yediyurappa was reduced to nothing more than a token leader with limited powers to govern within the framework given by the high command.

During PM Modi’s visit to the state in January 2020, Yediyurappa, while sharing a stage with the PM and several other Union Ministers, made an appeal for the Union government to grant the state’s request for special funds for flood relief work. The then-CM openly stated that he had taken it up with PM Modi at least three or four times but to no avail. This public request brought much embarrassment to the BJP high command, and a call later reportedly asked Yediyurappa to not issue such public statements against the Union government or its leaders in the future.

In 2020, the Union government gave two options to states to make up for the shortfall in GST revenues expected. The Union government said that the states can borrow either Rs 97,000 cr or the entire Rs 2.35 lakh cr. Five non-BJP ruled state governments — Kerala, Telangana, West Bengal, Punjab and Delhi — rejected both the options saying that this would put the burden on the states and the responsibility lies with the Union government. But Karnataka, like other BJP-ruled states, had to choose one of the two options given due to political compulsions. Sources in BJP tell TNM that given Karnataka’s precarious financial condition, Yediyurappa was not inclined to choose any of the options as he believed it would further push Karnataka into a debt trap. But under duress, he too, like other BJP CMs, had to toe the line of the party high command at the cost of further pushing the states’ financial situation into peril.

In November 2020, a politically cornered Yediyurappa decided to recommend granting other backward classes (OBC) status to Veerashaiva-Lingayat community. This was part of an agenda for a Cabinet meeting and was seen as a move by Yediyurappa to counter the protests by the Panchamasali sect of Lingayats asking for 2A reservation — which would give them a higher status in OBC reservations. Many believed that the Panchamasali protests were bolstered by a few BJP leaders, with the permission of the high command, to diminish Yediyurappa’s influence on the community. So with this recommendation, not only would he manage to consolidate all sects of the community behind him, but also put the central BJP in a spot as granting the status would antagonise other dominant communities and rejecting it would anger the Lingayats. But on the morning of the Cabinet meeting, Yediyurappa is said to have received a call from a very senior member of BJP who asked him to drop the issue. Under pressure, Yediyurappa conceded.

While the party supremo culture exists in most political parties in India, with national parties, the high command’s imposition often chooses to look at how a certain decision will impact the party’s electoral prospects elsewhere in the country even at the cost of compromising the state's interest.