Filmmaker Paromita Vohra does not preach, victimise, or bore you. In fact, the phrase ‘bore mat kar yaar’, now famous among various natkhat circles, is her coinage. However, reading the premise of her new film Working Girls, which premiered in Bengaluru on August 2 at the Goethe Institut/Max Müller Bhawan, I wondered how Paro, as she is lovingly called, would pull it off.

The producers of the film–Laws of Social Reproduction Project led by Dr Prabha Kotiswaran, King’s College, London– are a collective that studies women’s reproductive labour across the marriage-market continuum. The documentary was created based on their research.

Working Girls is fantastic. Travelling through the various locations of Madurai, Kolkata, Mumbai, Pune, Latur, and Thiruvananthapuram, Paromita met women who perform erotic dances, donate eggs, are surrogates, do sex work, agricultural labour, domestic and care work, and so on–work that is generally considered taboo, especially when done by women. The film sees them and shows their lives, gently entering each of these environments that are made infinitely complex not just by the socio-economic power dynamics, but also by ancient and troubling laws, patriarchy, and judgement.

The stories of the women in the film are often intractable, their work being deeply coercive, and often in hostile settings. At various times throughout the film, we are reminded of the famous feminist slogan ‘Returning from work, women return to work’. But the film does not attempt to immediately span across these spaces to instruct us on the tyranny that is staple for these women. Instead, it stays in each place with the women who inhabit them and quietly listens.

Their stories unfold while they look after children, cook, sit at dharnas, travel, meet in self-help groups, and get ready for work.

Working Girls employs much time and effort to stay in one place and allow for the narratives to emerge– perhaps with gentle yet persistent coaxing– an extremely nurturing filming process. The result is that each of the women becomes not ‘speaking heads’ as in most documentary films, but intriguing and delightful characters with compelling arguments about how they frame their own lives.

Kaushalya, the Aadal Paadal dancer, Kamakshi, the community worker, Rita, the agent for egg donation, and Sister Lily, who mobilised domestic workers, and many others in the film linger in our hearts more than just as representatives of their journeys of struggle, but as voices that often echo our own prejudices about women’s work.

Another aspect worth mentioning is the way Paromita has used humour and irreverence to emphasise the legal structures and policies that control and often subjugate women. In a style that has now become a Paromita Vohra trademark through the brilliant platform that she has built– Agents of Ishq-- she delivers the sometimes mundane and often ridiculous world of governmental discipline through hilarious animation and commentary. Wrecking colonisation, nationalism, patriarchal morals, and upper caste hegemonies for their impact on the lives of ‘working girls’, these sections of the film made the whole auditorium burst into raucous laughter, time and again.

But what is most breathtaking is how Working Girls is steeped in the chutzpah of the women whose lives it follows. Right next to heartbreaks are also bonds of affection and the solidarity of sisterhood. In the thick of everyday struggles to survive, there were moments of exquisite pleasure: felt, expressed, witnessed in their bodies, their glances, their touch. Their wit and sense of irony compel us to re-examine not just what, but how we define the sacred and profane. The delicate camera movements, holding space for their personal and intimate moments, make the scenes particularly extraordinary.

However, the film could have given more time to the stories of the domestic and care workers. They seemed to end too quickly, leaving a lot unsaid, unlike the other stories. I do hope Paromita makes more films with the material she has shot with these women.

At the end of the screening, the room was abuzz with laughter, curiosity, and a sense of camaraderie. There was also a palpable acknowledgement of how the world at large gets offended when women want to work, earn, and live lives on their own terms. The film lays bare how this aggression is most sharply and damagingly felt by those who live in the margins, doing work that is subjugated and morally scrutinised over and over.

For many of us, viewers, the screening was almost like a reunion– a meeting of friends and co-travellers from across movements, protests and other socio-political engagements. There were also many younger faces, who made the post-screening conversations extremely enriching.

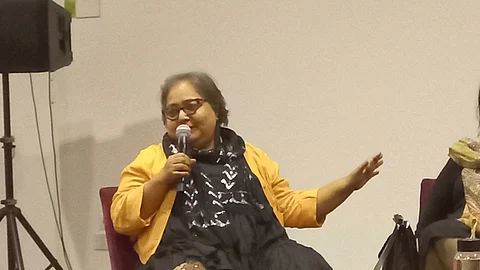

Most of all, what stayed with us was Paromita’s response to a young student: “We need to be able to see and move outside of our middles class lives, walk the streets with those who are fighting for their rights, listen to arguments unfamiliar to us, and understand why all our lives are tied together in deeply intricate ways.”

Arundhati Ghosh is a writer and cultural practitioner living in Bangalore.

Views expressed are the author’s own.