I had zero interest in cookbooks. Once Aparna was convinced I didn’t care for the books, she dropped them off by Seema’s bed. Then she rushed back to me and told me about school in whispers. Nazia had called on the landline and my mother had told her I was in the hospital.

‘Does she know which hospital?’

‘Hmmm.’

‘Is she going to visit?’

She shrugged.

That put me in a better mood. My mother was talking to Seema, but her eyes were on me and my sister. So, I lowered my voice too.

‘If she calls again, tell her to come visit me after the surgery,’ I said.

Aparna’s face fell. ‘You are going to have surgery?’ ‘Didn’t Amma tell you? They are going to take skin from my thighs and put it on my arm.’

‘What?’ it was her turn to whimper.

Then she ran out of the hospital room. She never visited me in the hospital after that day. I was glad she reacted like that, because I had never shaken off the guilt of having been healthy, wolfing down cakes and Chinese food as Aparna lay in a hospital bed during her surgery. Even though I was smiling, my mother was still scowling at Aparna. When she saw me staring at her, she assumed a regular face, and then slowly tried to smile at me. I looked away. She had done this to me, she was why I needed the surgery. How could she sit there looking guiltless? My sister felt guilty. How could my mother come there, showing off her unblemished face and arms to me, showing off her health so shamelessly? As all the anger I had pushed inside came back, I leaned on an old, reliable habit. One I had perfected as a child before I had the words for my anger. I took aim at the bed pan—no one except Seema and my mother could see what I was doing—and peed right there in front of them. I had threatened to do this countless times, in crowded spaces when I was scared, when I wanted to leave some place, when I felt suffocated by the mobs on Fridays in temples, and those long queues to meet oracles who read faces, palms, cowry shells, what have you, swamijis and gurujis, horoscope readers and numerologists, in that phase of hers when she believed in every voodoo prayer that ever existed.

My mother’s face assumed the same darkness that had taken over Aparna’s face before she ran out. It was identical. Then she opened her mouth to say something, stopped, walked closer to my bed, wiped my face with her saree, and said, ‘You can’t do that when there are other patients here, you could give them an infection.’

She knew it would make me angrier, and she seemed to revel in having said something so appropriate, so considerate, so classy in front of the other lady.

She turned and said, ‘Sorry, Seema. He has a, umm, temper problem.’

I nearly screamed then, but I had resolved to die without ever saying a word to her again. Which I was possibly going to now. If you are fifteen, and admitted to a ward like this, and had surgery lined up, you could of course die. Then I remembered what I’d told Aparna, and I began to get really mad at myself. Why did I ask her to tell Nazia to see me after the surgery? What if I was dead by then? I was beginning to feel that lump in my throat again.

My mother might have seen the panic in my eyes, or Aparna might have sensed through that sibling connection of hers that I wanted to see her again, I don’t know how, but a few minutes after my mother left the ward, my sister came back in to say bye.

‘Can you tell Nazia to come see me before the surgery?’ ‘Are you going to die?’ she asked.

She began to sob loudly. My mother peeked in and glared, and Aparna stopped crying immediately. The tears didn’t stop, just the noise from her throat did. Her face crumpled like a newborn piglet, saliva dripping, her misaligned teeth on full display. It was at once gut-wrenching and sickening to watch.

‘Don’t cry here,’ I said in that curt way my mother did, holding my index finger to my lips. ‘And don’t come to visit me here, you or your mother.’

I felt a bit relieved after they went away.

I looked across at Seema to see if she was judging me.

She just shrugged, ‘Hey, that never ends, by the way.’

‘Hmm?’

‘These fights with your parents. Somehow with age, it seems to get bigger, uglier, more painful.’

‘Wait, do your parents hit you even now?’

She laughed, ‘I meant pain here, and here,’ she said pointing to her head and her gut.

‘Here?’ I asked, pointing to my throat.

‘And here,’ she said pointing to her butt, and we both laughed.

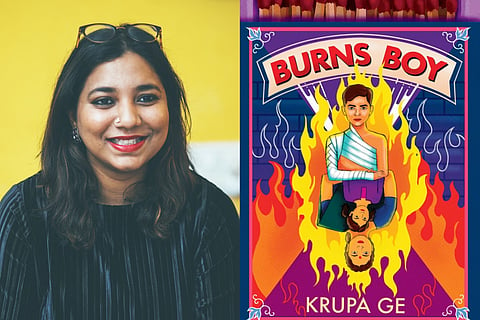

Excerpted with permission from “Burns Boy”, by Krupa Ge, Westland Books.