Farishteh

Havovie and I followed the path of hexagonal grey stones that led from the cottage she and Uncle Darius shared to the banquet hall. Her glossy black hair gleamed in the afternoon sun. If she stood still, I’d probably catch my reflection in it. Uniformed gardeners waved at us as they hosed the lawns and flowering bushes before the club’s guests emerged from their siestas.

‘Remember Farishteh, if anyone asks, we’re cousins.’ Havovie expected everyone to obey her edicts even when she came up with implausible scenarios.

‘What’s the sense of lying, Havovie? What if they discover we’re not related.

‘I don’t know how else to explain the intimacy between our families.’

‘Their opinions shouldn’t matter. We’re never going to meet any of them again. And this cousin’s story isn’t believable. We don’t even belong to the same faith.’

With a swing of her shoulder-length bob, she turned around. ‘That’s what makes us different from everyone else.’

‘Nor do we look similar from any angle ’

‘I told you the obvious is boring. To make people wonder is the fun part.’

I stood half a head taller than Havovie. She was pale like Lady Feroza, while I had inherited the florid complexion of our purported Central Asian ancestors.

‘It’s too late now. Everyone at the club thinks we’re cousins.’ After a pause, she said, ‘Daddy is a strange man.’

Had she just realized that? I wondered. Aloud, I said, ‘Surely, you don’t mean that.’

‘I most certainly do. The highlight of his day is to play billiards and tennis with your father in the mornings and to dine at Lyndewoode House every evening. Between your father and Uncle Haaris, no one else gets a word in edgeways, and your mother’s always drifting off to sleep. Yet, he enjoys their company and ignores the women at the club who throw themselves at him.’

He must prefer to pay attention to women who paid him none—like Mama. ‘Why would you want your father to be interested in other women?’

‘You have met my mother, haven’t you?’

Ever since we were little, Aunty Ava seemed to exist in her own world. But that afternoon on the verandah, she had been nothing more than a shell inhabiting a body. Her eyes looked soulless.

‘Daddy says she needs to be institutionalized. None of my grandparents are in favour of the idea.’ Havovie spoke in a detached tone one would use to discuss a stranger.

The word ‘institutionalized’ was new to me. I guessed it meant when hospitals locked up crazy people. Fortunately, Havovie didn’t press for a reaction and when we arrived at a door with a pair of paper lanterns on either side, she said, ‘This is it.’

Inside the banquet room, the green, blue and red of the wall streamers reflected the dimmed lighting and cast an orange hue on the people and tables and chairs. A ripple of excitement ensued in all corners at Havovie’s arrival. Boys stared at her in frank admiration, while girls huddled in clusters of twos and threes passed hushed comments behind covered mouths. She strode over to the drinks table and poured herself a glass of root beer. I did the same, but the foam spilled over the top of the glass. Books made out root beer to be so delicious—but it tasted rather bitter.

Lips pursed, Havovie said, ‘Why are you making a funny face?’

‘I’m not.’

The banquet room door opened, throwing a beam of light on the parquet floor. One by one, four uniformed male figures entered. Everyone’s attention shifted from Havovie. They glided across the room—bluish-grey apparitions, stopping now and then to shake hands with some awe-struck boys and tip their caps at moony-eyed girls. The root beer was making my throat burn and my eyes water. I blinked away the salty, false tears and gazed into the long-lashed, heavy-lidded eyes of Saleem El Edroos.

‘Good afternoon, ladies . . . it’s nice to see you again . . . Farishteh.’ In that orange light, Saleem performed his signature salute in slow motion.

Havovie glowered at me. Burning, no doubt with curiosity about when Saleem and I first met.

Fortunately, Saleem himself started the introductions. ‘I’m Saleem and these are my course-mates: Asif, Chowdhry and Chopping.’

‘Pleasure to meet you all,’ said Havovie suddenly all smiles.

Other than Saleem who was clean-shaven, the rest sported trim, clipped moustaches. They seemed much more grown-up than the other boys around. But none of them were over twenty. Tightening the sash of my frock around my waist, I asked, ‘What brings you to Ooty?’ The last I had heard, Saleem was in

Poona.

‘I’m training at the Coimbatore flying school again.’ Saleem helped himself to a paper cup of lemonade. ‘We have three days’ leave, so I came to see my father.’

I knew, of course, that General El Edroos was in Ooty. Dadajaan had invited him to his seventieth birthday celebrations next week.

A gramophone blared a Glen Miller song. Havovie patted Saleem’s arm. ‘Let’s dance.’

Saleem gallantly put down his lemonade and followed Havovie to the dance floor. Typical of Havovie to grab the most handsome boy in the room.

‘This song has such silly words, doesn’t it?’ said Chopping. ‘Yet, it’s the rage in all America and England.’

‘Right,’ I said, half expecting him to ask me for a dance. But he didn’t. Like all the other boys and girls at the party, he was watching Saleem and Havovie who’d taken centre stage on the dance floor. Saleem bowed and Havovie’s slight form dipped in the faintest of courtesies. Saleem offered her his left hand and placed his right hand on her waist.

Havovie’s pink skirt lifted in the air and twirled as Saleem spun her around. The entire party caught a glimpse of her lacy bloomers. And there I was, self-conscious to be wearing a frock that exposed my shins.

‘We have a lot of dance parties in air force bases,’ explained Chopping. ‘Saleem can be on the dance floor for hours together.’ Saleem must take after his father in that regard. General Edroos was supposed to enjoy dancing. Pegasus’s ballroom was

fabled in Hyderabad. ‘That’s nice,’ I said.

Asif and Chowdhry were now dancing with a pair of girls from Havovie’s school in Bombay. Gradually, the number of couples on the dance floor swelled. They were all adept dancers, but none as graceful as Havovie and Saleem. Chopping spooned a teaspoon of ketchup and a handful of wafers on a foil plate and handed it to me. As I stuffed a bunch of wafers into my mouth, a squeaky voice asked, ‘So, you’re Havovie’s cousin?’

I turned around to face a trio of girls all wearing the meddling expressions of old Hyderabadi women. If they thought any of Havovie’s stardust had sprinkled on to me, they were mistaken.

‘Yes, I am.’ Contradicting the lie wasn’t worth the effort. ‘Is your mother the shah of Iran’s niece?’

‘Are you related to the princes who are on holiday here in Ooty?’

Goodness, a lot of gossip circulated among teenagers at Ootacamund Club.

‘Do you mean the Nizam’s grandsons? No, I’m not related to them.’

‘Isn’t the resemblance between Havovie and her striking?’

Somehow, Saleem had evaded Havovie’s clutches and stood beside me, sipping lemonade from a cup and he muttered, ‘Almost embryonic ’

I’d learned about embryos in Botany and didn’t understand why Saleem was comparing Havovie and me to one. His vague statement dampened the curiosity of the girls badgering me with questions. They faded away until they became one with the balloons and streamers on the walls. My heart pounded so loud; I was certain Saleem could hear it. If he asked me to dance, he’d discover I had two left feet.

‘So, this is it our last summer under British Raj,’ he said.

‘India will be both free and divided isn’t that ironic?’

I could think of no suitable reply, other than what Dadajaan repeated every day. ‘I hope they solve the problem of the princely states before they leave.’

‘Your grandfather is a frequent visitor at Pegasus,’ said Saleem. ‘He tells my father you’re of great help to him.’

‘He wants me to help him with his correspondence. But I’m still a novice at typing,’ I said. The sash around my waist suddenly began to feel too tight. ‘So, I couldn’t have been of that much help.’ It was odd that Dadajaan discussed such a trivial matter with

General Edroos.

‘The limitations faced by his troops frustrate my father a great deal,’ said Saleem. ‘He hasn’t had much luck with the transitional government yet.’

I’d overheard Dadajaan discuss this topic a great deal. Of course, it wasn’t my place to say so.

‘Was it difficult to be accepted to the air force?’ I asked. ‘Well, the initial form has three columns: army, navy and air

force. We’re supposed to tick them in order of our preference. I ticked air force, of course. Then I underwent a medical exam and a mathematical aptitude test.’

‘Doesn’t the air force select the best sportsmen? My father mentioned something to that effect.’

Saleem’s face flushed a bit. ‘I play tennis.’

He must not want to say that he must be an excellent player. ‘Do you?’

‘Have you?’

We both said at once. ‘You first,’ said Saleem.

‘Have you been up on a plane yet?’ I asked, regretting my question at once. What else would an air force cadet do other than go up on a plane?

‘Yes, but only with an instructor, never alone. It’s the most wonderful experience imaginable,’ Saleem answered in a patient tone. ‘I remember playing with a wooden aeroplane in your nursery. Do you still have it?’

‘Yes, we do.’ What else did he remember? I was dying to ask. I waited to see if he himself would volunteer some information. But he didn’t. Instead, he gave me a polite smile and said, ‘I’ll catch up with you later, then.’

He left me standing all by myself with my cheeks burning. I loosened my sash and took a deep breath. Still, talking to him and worrying about not asking silly questions had been a strain. Saleem stood close by chatting with Chopping. They didn’t bother to include me in their conversation. Asif and Chowdhry didn’t leave the dance floor. I stuffed myself with wafers and kept glancing at the clock. Only half an hour to go before the jam session ended. At exactly seven, the bearers switched off the lights and the gramophone. What a relief, I had no intention of attending any more jam sessions.

Saleem reappeared at my side, yet again, and so did Havovie— flushed with exertion. She hadn’t sat out for a single dance. Sweat plastered her glossy hair to her scalp. ‘Farishteh, I can’t believe you didn’t dance even once.’

‘We were too busy discussing the old days,’ said Saleem.

Havovie looked from me to him as if trying to figure out our secret shared past. Little did she know all it contained was a wooden aeroplane. ‘Can I escort you girls to your motor or cottage or wherever you are going?’ asked Saleem.

‘No need,’ said Havovie, in a no-nonsense tone.

Really, did Saleem think us incapable of finding our way back or something?

We’d reached the door of the banquet room when he called out. ‘The shah of Iran story was certainly amusing, but the cousins story was a bit of a stretch.’

Havovie ignored Saleem’s comment. A steward handed us an umbrella to share. It had drizzled while we were inside the banquet hall. A film of water had collected on the grey stones.

‘Why are you in a bad mood? No one danced as much as you did.’

‘Saleem would have danced with me the entire time had he not felt sorry for you standing alone eating wafers. Why didn’t you ask Chopping to dance with you? Pilots can never say no to a lady.’

‘Since when have you become the expert on pilot behaviour?’ It was rather difficult to fight with someone while sharing the same umbrella, but Havovie could be exasperating. I raised my voice. ‘You don’t know everything about everything.’ Havovie shut up. She was just being herself. But Saleem El Edroos’s behaviour had indeed confused me. It was impossible to tell whether he was being nice to me because he liked me or out of imposed politeness.

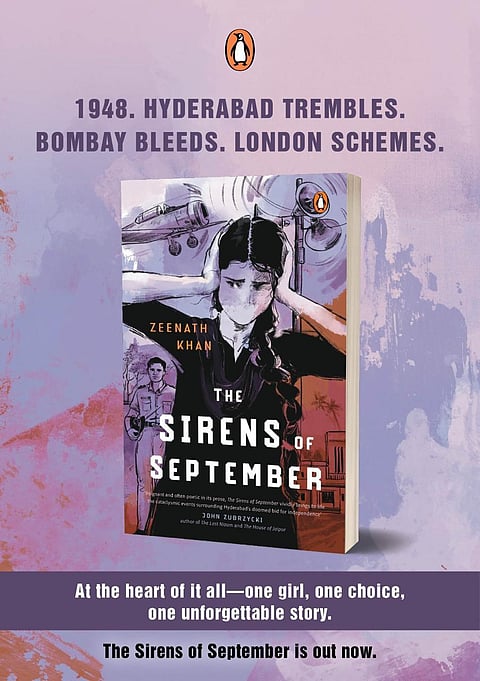

The Sirens of September is Zeenath Khan's debut novel published by Penguin India in September 2025.