Here’s some worrying statistics that UNESCO recently released in its 2019 State of the Education Report for India - Children with Disabilities: 75% of children with disabilities (CwD) in the age of 5 and one-fourth of them in the age group of 5 to 19 do not attend schools or any educational institution. What’s more, the number of children enrolled in school has been considerably collapsing with each successive level of schooling.

This is the education system for students with disabilities in India; a reality that has been ill-conceived in the Draft National Education Policy (NEP) 2019. According to the draft, the new education policies have been founded on the principles of access, equity, quality, affordability and accountability. However, it looks like the concept of access has not moved beyond the exigency of ramps and handrails for students and teachers with disabilities.

The draft currently lacks a sense of meaningful inclusiveness of students with disabilities, points out a group of organisations and individuals working with persons with disabilities. In a comprehensive response letter to the Minister of Human Resource Development (MHRD), these experts have called for inclusive education to counter stigmatisation and discrimination of persons with disabilities (PwD) in society.

In addition to suggesting a series of recommendations for inclusive education and classroom practices for children with disabilities, they have also identified policies in the draft that lack inclusiveness in terms of access, teaching methodologies, facilities at school, funding and programmes for students and teachers with disabilities as well as their caregivers.

First, time to change vocabulary

Neither disability groups nor Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment (MSJE) and Department of Empowerment of Persons with Disabilities were consulted during the initial drafting process, points out Amba Salelkar, one of the activists who drafted the letter and a lawyer with the Equals Centre for Promotion of Social Justice.

The draft NEP speaks about CwD in only a few areas. In the sub-chapters on CwD, the draft uses terms such as “special education” and “children with special needs”. These terms have to be done away with, say disability rights activists in the letter.

“Students with disabilities should not be seen to need ‘special treatment’; rather they need accommodations in order to be able to study like everyone else. The term ‘children with disabilities’ is in accordance with the Rights of Persons with Disabilities Act, 2017. Besides, the use of terms such as CWSN (Children With Special Needs) and differently-abled in the document could confuse the stakeholders and duty bearers,” say disability rights activists in the letter.

How policies cannot be discriminatory, stereotyping

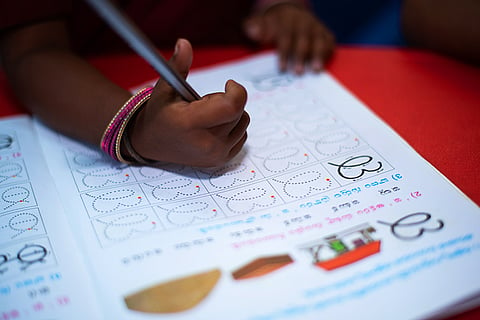

Experts also pointed out that certain policies are currently discriminatory in nature or are suggestive of exclusion. Many harbour a preconceived notion that CwD lack the ability to learn, and exclude from the development of foundational literacy and numeracy. That’s discrimination. The needs of such students should be included when designing the curriculum on sex education, physical education, yoga, art, music or dance.

The failure to make reasonable accommodation is a form of discrimination, say experts. Reasonable accommodation refers to the necessary and appropriate modification and adjustments to the environment to enable persons with disabilities (PwD) to enjoy and exercise their rights equally with others.

“Without those accommodations, the right is pointless,” Amba tells TNM. “For instance, a school doesn't discriminate in admissions, but if it doesn't provide blind students with braille books, that’s discrimination.”

Stereotyping children with disabilities, especially those from marginalised communities, is common. Schools should not conform to stereotypes and push a student with visual impairment to take up singing classes or a similar form of art, if he or she is not interested in pursuing it. “Curriculum must be audited for regressive and outdated references to persons from marginalised communities, including PwD; example, the perpetuation of stereotypes about leprosy in school biology textbooks,” say experts.

Amba explains why: “Special schools are not treated on par with schools under the MHRD. There’s an exclusion in teacher benefits, application of the Right To Education (RTE), syllabus, mid-day meal and even the certification that students get on completion. CwD cannot get admission to a vocational course with a special school certificate.”

Harmonised Guidelines

Harmonised Guidelines and Space Standards for Barrier-Free Built Environment for Disabled and Elderly Person, 2015 is the foundation to inclusive education. These guidelines provide a framework to facilitate inclusive designs of public and private spaces to ensure greater accessibility for PwD and empower them to participate in the development of society.

These harmonised guidelines are not extended to only infrastructure, but to mid-day meals as well as the academic, social, extra and co-curricular aspects of school.

Currently, the mid-day programmes exclude CwD, point out the experts. These students don’t have the means or support to put the food on the plates or mouth, or are not given assistance while eating. As a result, many go hungry or have meals at home. In the latter case, many don't return to school after the noon meals. The experts suggest adequate staff to support children who require assistance.

Toilets, drinking water facilities, playgrounds, libraries, staffrooms and canteens on the premises of schools, colleges, teaching universities and research institutes should be fully accessible for students and teachers with disabilities.

Students with visual impairment should have access to tactile books (books consisting of raised shapes and read with fingers) and study material. The proposal to revive Indian languages should also include the Indian Sign Language and regional sign languages.

Under online programmes, videos should be subtitled, provided with audio description, and made available with sign language interpretations. Technological interventions, proposed in the Draft, should also be designed for CwD, who can enjoy greater participation in the classroom through technology.

Need to curb dropouts

One of the points that the Draft has rightly identified is that distance from the school to house - in addition to inaccessibility to school infrastructure, including bathrooms - has contributed to high dropouts and low enrolment rates among CwD.

And so, the current proposal to “consolidate existing stand-alone primary, upper primary, secondary and higher secondary schools into composite schools/school complexes” will not facilitate “the correct identification of the barriers to enrolment and continuing education in India, particularly for CwD”.

Families are not provided access to transport and escort allowances. The disability rights experts suggest that “transport-related disbursements need to be given from the department of education and not from the department of disability or social justice, and accessible transport, which prioritises the dignity and safety of students, should be ensured, keeping in mind the local terrain and conditions”.

Home-schooling vs home-based education

The policy coalesces “home-schooling” and “home-based education”, a point that activists insist on removing. “It violates the rights of CwD and promotes isolation and denial of services in the guise of the “best interests of the child. Besides, these children rarely learn anything from education services at home,” says Amba.

Home-schooling is a choice made by families who have the means to educate their child at home. Home-based education (HBE), on the other hand, is an exception under the Right to Education (RTE) Act, wherein CwD - who fall under the National Trust Act, 1999 (autism, intellectual disabilities, cerebral palsy and multiple disabilities) or otherwise ‘severe’ disabilities - can opt for receiving education services at home.

“Besides, this system requires at least one parent to remain with the child full time, forcing them to take on the role of caregiver and educator, while ignoring the views that they or their children have in this regard,” say activists.

Other ways to promote inclusive education

The National Scholarship Fund should also include scholarships for CwD in higher education. This should include hostel fees and variable additional costs like having to travel with an escort. However, this should be exclusive of the investments in accessibility and assistive devices (such as braille printers, scanners, employment of sign language interpreters) that the Higher Education Institutions has to make.