Chapter 3: The Fight to burn women alive

Lord Hastings, who was governor general at the time, was wary of legislating on Sati, let alone ‘an absolute and peremptory’ law, for fear of offending upper-caste soldiers. ‘I was aware how much danger might attend the endeavouring to suppress, forcibly, a practice so rooted in the religious belief of the natives,’ he wrote. ‘No men of low caste are admitted into the ranks of the Bengal army. Therefore, the whole of that formidable body must be regarded as blindly partial to a custom which they consider equally referable to family honour and to points of faith. To attempt the extinction of the horrid superstition, without being supported in the procedure by a real concurrence on the part of the army, would be distinctly perilous.

Thus, the practice of Sati continued with ‘unabated vigour’, as did the attendant abuses. Hastings’s successor, Lord Amherst, too stayed clear of the issue. In a minute written in March 1827, when his five-year tenure was drawing to a close, Amherst declared: ‘I am not prepared to recommend an enactment prohibiting Sati altogether.’ He argued that Sati could be banned only when the people were ready for it. ‘I must frankly confess, though at the risk of being considered insensible to the enormity of the evil, that I am inclined to recommend to our trusting to the progress now making in the diffusion of knowledge among the natives for the gradual suppression of this detestable superstition. I cannot believe it possible that the burning or burying alive of widows will long survive the advancement which every year brings with it in useful and rational learning.’

This was where things stood when William Bentinck succeeded Amherst in July 1828. He did finally venture to outlaw Sati in December 1829, in large part because of the reassuring feedback he had obtained, as detailed in his minute written a month earlier. He had sought the opinions of forty-nine army officers holding key positions, and of the five judges of the Nizamat Adawlat, then the highest criminal court. The feedback convinced him that the time for legislative intervention had come, and it would ‘wash out a foul stain upon British rule’.

Bentinck’s minute of November 1829 pointed to the 1817 regulation, the very existence of which proved ‘the general existence of the exception’ that had been made for Brahmins. He said that it was ‘impossible to conceive a more direct and open violation of the shasters, or one more at variance with the general feelings of the Hindu population’ than the 1817 regulation. For good measure, he added: ‘To this day, in all Hindoo states, the life of Brahmins is, I believe, still held sacred.’ Yet, the British administration had chosen to legislate equality across castes in respect of the death penalty.

Bentinck’s regulation, passed in December 1829, began with a culture-neutral declaration that the practice of Sati was ‘revolting to the feelings of human nature’. He followed this up by challenging a culture-specific stereotype: ‘It is nowhere enjoined by the religion of the Hindoos as an imperative duty’. Given that widow marriage was still nowhere close to being legalised among upper castes, Bentinck held that ‘a life of purity and retirement on the part of the widow is more especially and preferably inculcated’.

He pointed out that, in many instances of Sati, ‘acts of atrocity have been perpetrated which have been shocking to the Hindoos themselves, and in their eyes unlawful and wicked’. Discarding Minto’s approach of running with the hares and hunting with the hounds, Bentinck’s regulation displayed his own ‘conviction that the abuses in question cannot be effectually put an end to without abolishing the practice altogether’.

Dispensing with the distinction between lawful and unlawful Sati, the regulation treated it as an offence in all circumstances. It clarified that those who were convicted of ‘aiding and abetting’ in the sacrifice of a Hindu widow, ‘whether the sacrifice be voluntary on her part or not’, shall be deemed guilty of ‘culpable homicide’.

A provision this stringent was more than what even Rammohan Roy, the progressive Brahmin who led the Indian campaign against Sati, had bargained for. Rather than ‘any public engagement’ that might ‘give rise to general apprehension’, all that Roy advocated in a conversation with Bentinck, according to the latter’s minute, was that the practice be ‘suppressed, quietly and unobservedly, by increasing the difficulties, and by the indirect agency of the police.’

Roy’s biographer, historian Amiya P. Sen, acknowledged this, noting that, when compared with Bentinck, the social reformer was on the side of ‘restraint and caution’. That said, once the regulation had been enacted, Roy presented Bentinck with a ‘congratulatory address’ signed by about 300 eminent Hindus, thanking him for ‘rescuing us forever from the gross stigma hitherto attached to our character as wilful murderers of females.’

Most radically, for aggravated forms of Sati, the regulation empowered the Nizamat Adawlat to impose no less than the death penalty. This ultimate punishment was prescribed for persons convicted of using ‘violence or compulsion’ or of having assisted in burning alive a widow who was or had been put under ‘a state of intoxication or stupefaction or other cause impeding the exercise of free will’.

The unapologetic combativeness of the 1829 regulation was perhaps the only instance throughout 190 years of colonial rule where a social legislation was enacted without offering any concession to orthodox sentiments. This was all the more remarkable for the fact that, in legal terms, the East India Company was still primarily a commercial enterprise. It was not until the British Parliament passed the Charter Act in 1833 that the company formally became a governing body. That was when Bentinck was upgraded from the governor general of Bengal to the first-ever governor general of India.

By then, through a fresh enactment in 1830, his ban on Sati the previous year in Bengal had been extended in substance to the rest of British India. It took another twenty years for most of the princely states to outlaw the practice. Thus, long before Mahatma Gandhi famously deployed moral pressure against the British Empire, Bentinck had pitted the same force against the caste and gender prejudices intrinsic to Sati. By criminalising this one native custom that had so corroded the colonised, the coloniser scored a moral point.

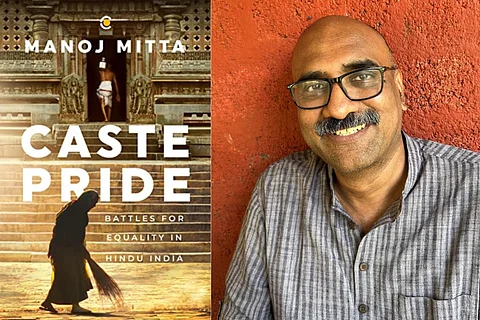

Excerpted with permission from Manoj Mitta’s ‘Caste Pride: Battles for Equality in Hindu India’, published by Context, an imprint of Westland Books.