In 1975, Indian cricket had its Oliver Twist moment. A tall, wiry teenager representing Haryana was participating in a national under-19 coaching camp at the CCI in Mumbai’s scorching summer heat. The camp was being run in true military style by Colonel Hemu Adhikari, former India player and one of the few armed services officers to represent the country. The players weren’t even allowed drinking water during the practice. The young man had bowled four hours on the trot on a hot and humid morning and was famished. When lunch was served, there were two chapatis and dal kept in the plate. The sixteen-year-old turned to the CCI secretary, Keki Tarapore, with a request: ‘Sir, these two chapatis are not enough for me, I am a fast bowler and need more food.’ Tarapore looked at him and laughed. ‘Young man, there are no fast bowlers in India so please don’t give me this bullshit about wanting to be a fast bowler.’

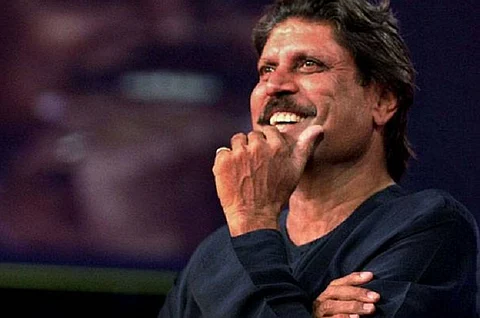

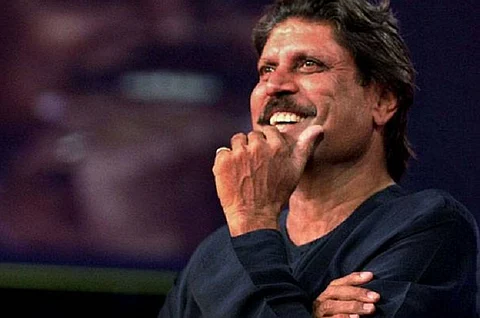

Sometimes, a stray remark can become a base camp to motivate an individual to reach the summit. Tarapore, a genial Parsee, had played one Test for India in 1948 as a left-arm spinner and was conditioned to believe that this was a land of spinners only. The desire to prove him wrong became a driving force for Kapil Dev Nikhanj. Not only did he get the full meal he asked for but he also achieved the seemingly impossible: he bowled fast for India. Barely four years later, as he became the youngest to take 100 wickets for his country, Kapil Dev sought out Tarapore at a function. ‘I just went up to him and said thank you. He had given me a goal in life by almost challenging me to bowl fast,’ he says.

Till Kapil Dev arrived, Indian cricket’s tryst with pace had been more in the nature of footnotes in history. In its fi rst Test in 1932, the Indian team was blessed to have a pair of new-ball bowlers in Amar Singh and Mohammad Nissar, both well over six feet. The England star batsman Walter Hammond had remarked of Singh that he was ‘as dangerous an opening bowler as I have ever seen, coming off the pitch like the crack of doom’. Nissar was reputedly even faster, his broad chest and rippling muscles giving him the physique of a genuine quick. But by the time India achieved freedom in 1947, the fast bowlers, including Nissar, had mostly migrated to Pakistan. Partition divided the subcontinent but it also split the cricket talent by physical traits. Th e brawny Pathans were well equipped to bowl fast while the relatively smaller Indians produced the slow bowlers. As Vinoo Mankad and Ghulam Ahmed spun India to its fi rst Test wins in 1952, the die had been cast: India would be typecast as the land of spin. Th e one exception was Ramakant Desai, who was India’s premier new-ball bowler in the early 1960s, but even he was short of height (his nickname was ‘Tiny’) and not really express pace. In 1967 in England, India’s newball bowling was bizarrely handled in the fourth Test by Budhi Kunderan who had been chosen on the tour as a wicketkeeper. Kunderan ran in from a few steps and rolled his arm over in the gentlest possible manner, bowling 4 overs and conceding 13 runs. The Indian team had selected four spinners for the Test and Kunderan’s task was to ensure the ball lost its shine in the fastest possible time so that the spin quartet could take over. In fact, just before the game when captain Pataudi asked Kunderan what he bowled, his cryptic response was: ‘Skipper, to be honest, I don’t really know!’

It was in this spin-friendly environment that Kapil Dev was being asked to make a mark. ‘I guess those who controlled cricket at the time thought that if you are from Haryana then you must drive a tractor, not bowl fast with a cricket ball,’ says Kapil Dev. Which is why his journey from the cricketing wilds of Haryana to becoming India’s fast bowling icon is like no other in Indian cricket: his rise would defy every stereotype that existed at the time. This was a sport which till the early 1970s was primarily defined by the deeds of the batsmen from Mumbai and the match-winning spinners. It was an upper-caste, Brahmin-dominated sport played mainly in the country’s big cities (Only seven cricketers in the first fifty years of Indian cricket were born in rural India, three of whom played in the 1930s, and all of whom had to move to a metro city to learn the game.) To truly democratize the sport, Indian cricket needed a small-town hero to emerge, one who could become a potential trendsetter.

A political parallel can perhaps be drawn with the Green Revolution in the country in the 1960s and 1970s that exponentially increased agricultural productivity and empowered the farm community in rural India. Until the Green Revolution gathered momentum, Indian politics was ruled by an upper-caste, metropolitan elite. It was only after the 1967 elections that a middle-caste, agrarian leadership began to assert itself, thereby eff ecting a dramatic change in the character of Indian assemblies and Parliament. If the Green Revolution (and later the Mandal Commission report giving reservations to backward castes) changed the face of Indian politics, one man with his stirring deeds would trigger Indian cricket’s biggest revolution, one that started with a simple desire for a meal of more than just two chapatis.

Excerpted with the permission of Juggernaut from the book “Democracy’s XI” by Rajdeep Sardesai.

Democracy’s XI is published on Juggernaut.in