Appropriation – a term that seems to come up frequently in the past few years in our conversations – is complex. Although appropriation is present in all aspects of the social sphere, it is readily visible in areas of music, art and film due to its nature of consumption. In one of the latest instances, the Tamil song ‘Enjoy Enjaami’ has received multiple criticisms of appropriation since its release. The discussion of authenticity and appropriation around the song can perhaps be captured in these lines from Walter Benjamin’s landmark 1935 essay, The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction: “The presence of the original is the prerequisite to the concept of authenticity. ... This unique existence of the work of art determined the history to which it was subject throughout the time of its existence.”

The origin and original of ‘Enjoy Enjaami’ both occur from Valliammal (Arivu’s grandmother), who worked in Sri Lankan plantations experiencing subjugation and oppression. It is thus this “prerequisite of authenticity” that has made Arivu an original voice among a score of other rappers on the scene. He draws from his own experiences, including the joys of his life to write his songs. The reason Valliammal’s experience resonates loud, two generations later is because her authenticity of experience resonates across time. This is also exactly why folk songs of oral tradition remain etched in our collective psyches and memories.

Thus, we must respect and acknowledge the people who have brought to light these songs even though they may have been in our memories in bits and pieces. We thank and acknowledge them because they are for the first time in history putting it together in a cohesive manner which allows those of us without a written glorious history to connect with our culture and therefore, connect with ourselves. It is not just Arivu who must be given his due credit for ‘Enjoy Enjaami’, it is also Valliammal. Too often, Dalit trans-non-binary people and Dalit women bear the burden of being the carriers of wisdom and traditions, with no acknowledgement of their role in preserving the culture. We are not simply the bearer of the culture, we are also alchemists who transform it.

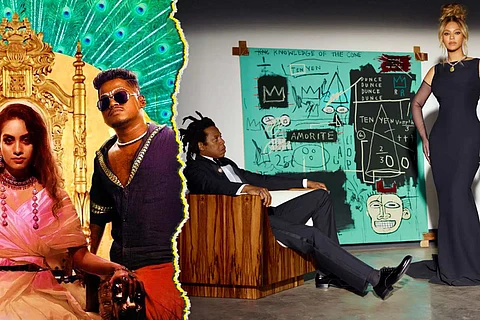

It’s also why Shan Vincent de Paul’s diss track and anger seems misplaced. He speaks about them (Eelam Tamils) being kept out (of the culture) in his diss track directed at Pa Ranjith. But he must also remember that Ranjith, Arivu and Valliammal belong to a caste who are not just oppressed in their own homeland but also discriminated across borders. For instance, Valliammal worked in the tea plantations in Eelam and although the geography changed, caste discrimination did not – in simple terms what Valiammal experienced was modern day slavery. Shan’s anger at Ranjith seems to disregard the fact that it is from a Dalit director and a Dalit artist that he received his first successful major feature film track which led to a Rolling Stone cover, even if the cover is promoting his unreleased album. Arivu shares a similar struggle and story and has worked for music and culture as Shan has, so a fellow artist should ideally have recognised the struggle and asked for the cover to be shared. It is simply not enough for Shan to ask us to see his struggle while he has not seen a fellow artist’s journey in music.

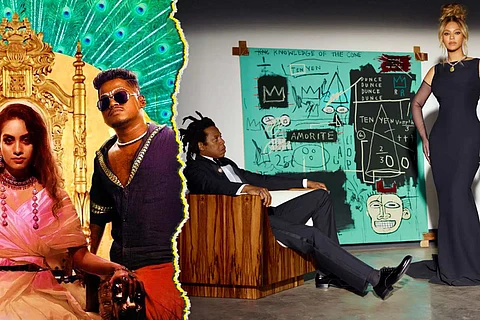

Recently, Beyonce and Jay-Z’s Tiffany ad featuring a Basquiat painting titled ‘Equals Pi’, with Beyonce wearing the iconic Tiffany yellow diamond, made global news. The ad will have Beyonce singing ‘Moon River’, a song from the movie Breakfast at Tiffany’s sung by Audrey Hepburn, who is one of the four people, including Lady Gaga, to wear the iconic yellow diamond. Even before the release of the ad, the pictures from the ad campaign came under much criticism. To a large part of the world, the ad is an expression of Black excellence — but to America, it may signify something else. Specifically to Black people, it may hold difficulty as it centres around issues of Black wealth and Black excellence.

Apart from issues of capitalism and consumerism that are promptly discussed, the Tiffany ad also denotes appropriation. We must remember that appropriation is more complex than people of two different races or castes co-opting work to gain benefit. In this case, the criticism is that Basquiat’s estate does not seem to receive any of the revenue generated from the painting. The criticism is also that the painting is being used as a way for a white-owned company (Tiffany) to further their sales while using Black artists, both current (the Carters) and past (Basquiat). Tiffany is profiting out of the social currency of being ‘woke’ enough to include Black people for their own interests.

To evade any questions of appropriation, the company has roped in the bigwigs of the music industry, especially Jay-Z who has expressed his love for Basquiat and owns some his paintings. Of course, as this Mic article points out, the Tiffany ad campaign, called ABOUT LOVE, is pledging money for HBCU (Historically Black Colleges and Universities) but it only makes the issue of cultural appropriation more complicated. Basquiat, although widely celebrated during his lifetime, did not receive the same financial benefit or opportunities. Even years after his death at the age of 27, his paintings did not sell for millions. As mentioned in this article, ‘Equals Pi’ did not find a buyer for a few years. And it has not been in public view for a long time. The fact that it has resurfaced and showcased to the public eye only as a way to further sales of a white-owned company should make it clear that it is being appropriated regardless of the Black artists representing it and the financial contribution to Black colleges is simply a way to evade accountability.

Such instances bring up questions around authenticity and appropriation. Who should be benefitting ultimately from a piece of art? Who are its audience? Authenticity is difficult to establish but it must be centred in whatever way possible.

Appropriation in the world of art history can be traced to various time periods where art has been reproduced. Its most notable recent past is the Dadaism movement whose purpose was to evoke political messages in the observer. Dadaism originated as a movement to highlight the absurdities and meaningless of war and violence. But some of the most iconic pieces of Dadaist art are standalone, often everyday, objects. The artists creating these works were a small circle who were influential and people of means who used everyday objects to communicate to the world the unspeakable violence of war. The artists who made use of appropriation in their art were speaking to a post-modernist ideal of decentring the artist, and rethinking what is good art or who is a good artist.

While such intellectual conversations are important and seems to move us forward as a civilization, what cannot be missed is that they (artists) profited immensely from this formulation. In many ways, artists who employed this technique of ‘appropriation’ or ‘reproduction’ were already from a background of privilege and/or power which may have played more of a role in establishing them as an authority of reproduction than the actual pieces of art they reproduced. If a person who did not belong to such a position had created the same art, it would have been easily dismissed as a mere imitation or copy. But, the famous artists like Andy Warhol that we know today seem to hold the mantle of expertise even in the art of reproduction.

Specifically to the Indian context, there can be no greater example than that of Brahmin-Savarnas who appropriate or reproduce by centering themselves in folk art, music and indigenous knowledge, which is simply a new mutation of the monster called caste. The history of such folk song erasure is not uncommon. Komala Totte, a folk singer who has not been credited even after she spoke in detail about her work being stolen, is a stark example of how the works of folk artists are often used in cinema where they reap no benefits. The reason given for such erasure is that folk songs and oral traditions belong to everyone.

Here we must pause and remember questions such as who can reproduce art? And who is considered original when they reproduce art? What power allows them to reproduce art and be taken seriously for it? What art is chosen to be reproduced? In the same manner, people who choose to call folk art or folk artists’ oral tradition as a form of art that belongs to everyone and seek to say, “look at the message/lyrics” and not the artist as a way to deny questions of accountability, are actually drawing from a long history of artists who removed themselves from the political messages they were expatiating.

We must recognise that as a country it is true that we have a rich oral tradition, but we also carry a strong literary tradition. We must recognise that access to lettering and recording came to a large population much later because of the oppression that Brahmins perpetuated. That does not mean that we must continue in the same tradition, a tradition of Brahminism.

Rachelle Bharathi Chandran is a writer and researcher whose interests lie in the area of aesthetics, pop culture deconstruction and intergenerational trauma in Dalit communities.