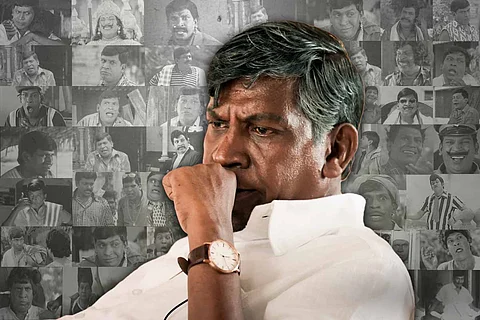

A storm called Vadivelu: Three decades on, the ‘Vaigai Puyal’ remains hard to define

Vennaam. Valikuthu. Azhuthuduven. Did you just hear these three iconic words in Vadivelu’s voice? If you did, it’s a testament to how much the celebrated Tamil comedian’s dialogues are burnt into our collective memory. It has been 35 years since Vadivelu, affectionately called Vaigai Puyal (Vaigai Storm) by his fans, was first seen on screen in En Thangai Kalyani (1988). The epithet is a reference to the famed Vaigai river that flows through the actor’s hometown of Madurai. All these decades later, Vadivelu and his work continue to defy both expectations and easy categorisation. Simultaneously, many of his dialogues have become embedded in spoken Tamil, offering succinct witticisms to use for everyday problems.

The actor has delivered some of the most memorable scenes in Tamil cinema comedy, offering counters and punch dialogues that land with seemingly effortless ease regardless of which big star he is paired with. The length and breadth of his work as a comedian, given his vast filmography of over three decades, is hard to summarise. Entering the Tamil cinema comedy space when the inseparable Senthil-Goundamani duo were at the peak of their popularity, Vadivelu slowly created a name for himself before going on to replace them as the mandatory comic relief.

Roles such as the inept lawyer Vandu Murugan (Ellam Avan Seyal, 2008), the village rowdie Soona Paana (Kannathal, 1998), the building contractor Nesamani (Friends, 2001) with his chaotic team of helpers, the vain and ineffectual police inspector ‘Encounter’ Egambaram (Marudhamalai, 2007), Kaipulla (Winner, 2003), and many more than can be listed here, would go on to define the kind of comedy Vadivelu offered — one primarily based on these characters being hopelessly bad at their jobs. This self-deprecating humour paired with unerringly timed punchlines and expressions that precisely convey the absurdity of the situation went on to create a fan base for the actor that remains dedicated to his work to this day.

Speaking to TNM, actor Nassar says, “Vadivelu has almost become for comedy what Sivaji Ganesan was to acting. But he’s too multifaceted to be considered only a comedian. In terms of his emotional range on screen, singing, etc., I would say that after Nagesh, there is only Vadivelu. When we both acted together in Em Magan (2006), he did not do just comedy scenes in the film, he became the character instead. I remember he had an emotional scene in the movie, all of us on set were moved to tears by his performance.”

Talking about Vadivelu’s early life before entering Kollywood, Nassar says, “Every time I commented to him on his prowess as an actor, Vadivelu always recalled his days as a theatre person. He used to be a part of small local theatre groups. Theatre training is one of the reasons he is such a good actor.”

Nassar also recalls working with Vadivelu for Imsai Arasan: 23rd Pulikesi (2006), directed by Chimbu Devan. The film was simultaneously a scathing political satire as it was a flexing of Vadivelu’s range as an actor. In a dual role, he offered comic dialogues that have now become embedded in everyday spoken Tamil, criticism of electoral image-building, and even a condemnation of the local impacts of globalisation.

An emotional range we often forget

The actor may be primarily known for his comedy, but fans have long wondered how much more he could do if given serious roles. In a handful of films such as Sangaman (1999) or Porkalam (1997) or even in religious films like Rajakali Amman (2000), Vadivelu showed a remarkable ability to move audiences. For many who grew up watching him for his comedy, the way Vadivelu handled highly emotional scenes came as a surprise.

Doubtless, this magic is what fans would have looked forward to seeing on screens again, in Mari Selvaraj’s Maamannan. Vadivelu was most recently seen in a minor role in Vijay’s Mersal (2017) and as a lead in Naai Sekar Returns (2022). The latter was widely anticipated as a comeback role but turned out to be a disappointing watch.

In Maamannan, Vadivelu stars alongside Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK) scion, actor and producer Udhayanidhi Stalin. Since the film is also produced by Udhaynidhi’s Red Giant Movies, it may be seen by some in the light of Vadivelu’s disastrous campaigning for the DMK in the 2011 Assembly elections. But coming from an established anti-caste director, Maamannan offers a pull for Vadivelu fans unlike any other in recent years.

Film critic and executive editor for entertainment at The New Indian Express Sudhir Sreenivasan tells TNM, “It is said that comedy is the hardest of all acting forms. Vadivelu himself has acknowledged this recently, when talking about how it was comparatively easier for him to play a serious character in Maamannan. I have always believed that all good comedy actors have character artistes within them. We have seen the late Vivek offering us many examples of this over the years. But apart from occasional glimpses, Vadivelu, despite a glorious career as a comedian, seems largely under-utilised in this department.”

Sudhir adds, “Even his casting in Maamannan took a filmmaker like Mari Selvaraj drawing from personal experiences and reimagining him in new light. What if we, for once, instead of laughing at his misery, empathised with him? It’s a powerful idea. There’s a natural innocence we associate with comedians and this means that their misery affects us in ways that even the hero’s suffering doesn’t. Among the joys of cinema is to experience actors being cast against type. When it’s someone of the stature of Vadivelu, the excitement is multifold.”

From the first look poster and teasers, it became immediately apparent that Mari was going to use a known comedy actor in ways Kollywood normally would not do. Mari did this previously with Yogi Babu, another popular comedy actor, in Pariyerum Perumal (2018) and Karnan (2021), making a point to move away from the casteist body-shaming the comedian is routinely subjected to in Tamil films. Instead, he was offered roles with dignity and nuance.

The lasting impact of such storytelling choices is what Vadivelu fans anticipated in Maamannan, which now appears to have the potential of a legacy-defining role. The actor’s performance as the titular character, in several key scenes, leaves you breathless. There is something particularly gut-wrenching about watching a figure so familiar to us all, as Vadivelu is, break down in grief, so absolutely isolated as his character is in Maamannan. His pain seemed to seep through the screen into a theatre that went deathly quiet, almost as a mark of respect.

Vadivelu the singer

Too often Vadivelu’s singing voice has been used as a prop for his comedy scenes. This is mystifying because his singing has the capacity to move one just as much as his acting does. The very first song credited to him was ‘Ettana’ from Ellame En Rasathan (1995) starring Rajkiran. Scored by Illaiyaraaja, this cheery number with Vadivelu dancing dressed as Michael Jackson continues to be a fan favourite. The same year, it would again be Illaiyaraaja who made him sing ‘Ammanuke Adangi’ for Rajavin Parvaiyile.

Through the following decades, Vadivelu would go on to sing for Kollywood’s most popular music directors including Deva, Harris Jayaraj, AR Rahman, and Santhosh Narayanan. But these songs still only add up to a handful. Yet, Vadivelu seems to be in his element while singing just as much as he is when in front of the camera.

In a recent interview, Mari Selvaraj told TNM, “Vadivelu would keep singing even in between shooting [for Maamannan]. Actually, most of what he sang on set were old, soulful songs. It’s only in movies that we see him sing for the sake of comedy. But outside of that space, he sings mostly deeply emotional songs. Even in Maamannan there are some scenes of him singing a few lines.”

Mari also mentions an interesting aspect of Vadivelu’s singing. “Vadivelu told me how he has no formal training in music. He sings entirely based on the emotions in the song. Both he and I were very keen that he should sing an emotional song for the film. I knew it would suit him very well.”

What the director says is apparent in the Maamannan song ‘Rasa Kannu’ sung by Vadivelu and scored by AR Rahman. This is also equally apparent in the short duet by him and Rahman at the film’s audio launch earlier this month. The two sang a few lines from the song ‘Mazhai Thuli’, also scored by Rahman for Sangamam in which Vadivelu had a supporting role as a folk musician. The lines refer to the daily struggles of a folk dancer and how it is despite his pain that he brings joy to his audiences. ‘Mazhai Thuli’ plays during a devastating experience for the protagonist in Sangamam. In the recent duet, one could keenly feel in Vadivelu’s rendition the same sorrow and devastation implied in the original.

Controversies and comeback

It was perhaps Vadivelu’s dabbling in electoral politics that proved to be his undoing. Campaigning for the DMK in the run-up to the 2011 Tamil Nadu Assembly elections, the actor locked horns with Desiya Murpokku Dravida Kazhagam (DMDK) chief and former actor Vijayakanth. The DMDK had allied with the All India Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (AIADMK) at the time and the alliance emerged victorious. For several years after that, apart from roles in small films, Vadivelu almost disappeared from the screen.

Worsening matters for himself, his clashes with Chimbu Devan and director-producer S Shankar, earned him a temporary ban from the Tamil Film Producers Council based on complaints by the two directors to the South Indian Artistes’ Association.

After this controversy, his sort-of comeback in Mersal was in a minor role that hardly demonstrated his calibre as an actor.

In 2022, he made what was hailed as an actual comeback with Naai Sekar Returns. It was to be a comedy entirely dedicated to Vadivelu and so garnered large-scale excitement. The title is a call-back to the character of Naai Sekar, a laughably silly would-be rowdie in Thalainagaram (2006) led by actor-producer Sundar C. Naai Sekar Returns made a score of such references to Vadivelu’s previous work, particularly much-loved characters like Nesamani and Vandu Murugan. Despite this, the film fell far short of expectations with one critic writing in The Hindu: “Naai Sekar Returns rides primarily on Vadivelu’s body language; his gorgeous facial expressions and the occasional punchlines he delivers. All of this makes you miss the man more. Is it enough to sustain an entire movie? No.”

The film, while taking its title from Thalainagaram, was unrelated to the latter’s story. Instead, it was an attempt at quirky humour featuring two rowdies who abduct pet dogs for ransom. With a plot – and villains – hard to distinguish from deliberate parody, Naai Sekar Returns did little to contribute to Vadivelu’s fame as a bankable comedian. Curiously, the actor was not part of the recently released Thalainagaram 2, despite his character’s continued popularity even 17 years after the prequel came out.

It also demands mentioning that not all of Vadivelu’s comedy has been harmless or endearing. Misogyny, transphobia, and homophobia are not new to Kollywood, and Vadivelu is no exception. A so-called ‘joke’ that vilifies LGBTQIA+ communities is the dialogue ‘avanaa nee’ from Gambeeram (2004). It is dismal knowledge that the sequence continues to be popular, despite queer people repeatedly calling out the homophobia underpinning the joke.

Kollywood ideas of caste and Vadivelu’s roles

Author and historian Stalin Rajangam writes extensively on Vadivelu in his book Tamil Cinema Punaivil Iyangum Samugam. In the chapter cheekily titled ‘Aana avarudaiya dealing ennaku romba pudichirukku’ – a reference to a famous Vadivelu dialogue – Stalin interprets a section of the actor’s comedy from an anti-caste perspective.

With examples of films like Winner (2017), Stalin writes that Vadivelu breaks the mould of toxic masculinity of intermediate caste pride reserved for the male lead. Referring to the rural Tamil Nadu genre of films that peaked in the 1990s, Stalin draws attention to the outward signifiers of a supposed ‘warrior-like’ male hailing from various powerful intermediate caste groups in the state. In these movies, a large moustache, gold jewellery, the aruval (machette), and violence are peddled as justice and symbolise the coveted ideal of an intermediate caste man (Thevar Magan, for example). These signifiers are an amalgamation of imagined caste supremacy. They also tend to be used almost without fail in films set in southern Tamil Nadu, the nerve centre of Thevar caste power.

It is these very signifiers, Stalin points out, that Vadivelu wears to comic effect. “His moustache is drawn on in Winner. Vadivelu swans around the town pretending to be a warrior. He carries the aruval, but when he challenges someone to a fight, his cohorts abandon him. He never wins a fight.” However, it should be noted that while this is an interesting lens to look at these films, it is perhaps only an incidental side effect of the directors’ choices to represent Vadivelu as the ‘unmanly’ antithesis of the warrior hero.

Compare this to his character in Thevar Magan (1992). Vadivelu plays a character called Esaki, who is implied to be Dalit, in a movie celebrated to this day for the performances by Kamal Haasan and Sivaji Ganesan. Esaki’s sole moment of humanity rather than comic relief comes only when he is brutally maimed by the villains. In a feud between warring Thevar factions, Esaki is an unimportant collateral damage. The same film valourises Thevars to the point of including song lyrics that say: ‘Potri paadadi ponne, Thevar kaaladi manne’ (sing in praise, girl, of even the dust beneath the Thevar’s feet).

In what became a long overdue call-out of Esaki’s representation, Mari Selveraj announced on stage at the audio launch of Maamannan that his film is an imagination of a life Esaki could have had. Mari also spoke with Kamal Haasan himself, present at the launch, of the mental trauma Thevar Magan caused him in his younger days because of the film’s casteism.

Vadivelu’s skin colour and other physical features have long been used in Tamil cinema as an example for undesirability. Take Kaalam Maari Pochu (1996), for example. Director V Sekher made several similar films at the time with three male protagonists, all working class, who are wastrels until their long-suffering wives correct their wayward habits. Vadivelu stars in all of these films. Paired opposite Kovai Sarala, the running joke in Kaalam Maari Pochu is that he is not the right match for his pale-skinned wife.

Vadivelu’s character is a corporation worker who sprays mosquito repellent for a living. He is shown as the crudest of the three protagonists and the one most inclined to domestic abuse. In a scene that is supposed to be comic, Kovai Sarala locks him in the house and beats him up in revenge. She also has several dialogues that degrade his skin colour. In the very same scene, in the background, is a picture of Dr BR Ambedkar. That this is the only scene in the entire film that shows an Ambedkar portrait inside a home is enough to conclude the filmmaker’s casteist idea of a Dalit man.

Watch: Mari Selvaraj interview on Maamannan | Thevar Magan | Vadivelu | Fahadh | Udhayanidhi