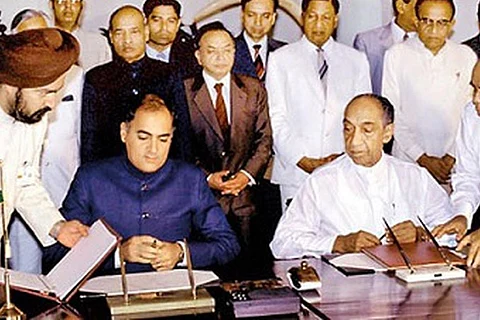

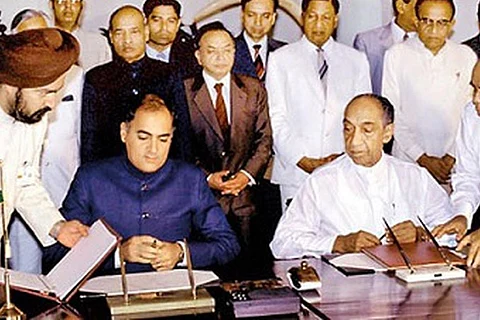

It has been thirty-five long years since an experiment failed to herald peace to Sri Lanka. One wonders what the island nation could have achieved if the key players had not scuttled the India-Sri Lanka agreement of July 29, 1987. When the pact was signed by Indian Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi and Sri Lankan President Junius Jayewardene, two Indian ministers shared with Gandhi their insight of the situation. External Affairs Minister PV Narasimha Rao wanted the agreement to be signed by the Tamil and Sinhalese, not by India. Minister of State K Natwar Singh wanted LTTE chief Velupillai Prabhakaran held back in India till his group surrendered the bulk of its arsenal.

Both arguments were overruled, for different reasons. Gandhi and Jayewardene had decided to shake hands (with a reluctant Tamil Nadu Chief Minister MG Ramachandran on board). But in Sri Lanka, both Tamil extremists and Sinhalese hardliners (who seemed to then comprise virtually the entire Sinhalese society) wanted the accord to fail. For Sri Lanka in general and its elite in particular, the Indian intervention was a blow. After having armed and trained Tamil militants, India had now thrust a fait accompli, because the military was about to overrun whatever area in Jaffna remained with the LTTE.

When Prabhakaran and LTTE ideologue Anton Balasingham returned to Hotel Ashok after meeting Gandhi on the night of July 28-29, hours before the Prime Minister flew into Colombo, Balasingham explicitly told me (I then worked for AFP) that the LTTE had decided to accept the accord. Events later proved that what the LTTE told Gandhi and the media were both far from the truth. Once back in Jaffna, Prabhakaran confided to a journalist from Chennai that he would “play games” with the accord, but his moves would be so subtle that no one would realise what he was up to.

He lived up to that promise. Even as mass protests by the Sinhalese gripped Sri Lanka against the agreement and the Indian military deployment, a string of events took place in the northeast that eventually pitted the Indian armed forces against the LTTE. By the time war ended and the last of Indian troops sailed home in March 1990, India had lost nearly 1,200 soldiers in a senseless war that brought no benefits to Tamil society at large.

The rest, as they say, is history. Prabhakaran avenged India's military war by assassinating Rajiv Gandhi. Unfortunately for him, his hand was uncovered, making him a pariah in both Tamil Nadu and India, leading, in the long run, to his increasing isolation and finally, to his death at the hands of the Sri Lankan state in May 2009.What would have been the scenario in Sri Lanka if the hardliners had not tripped the 1987 agreement or failed? There would have been limited autonomy in Tamil areas, which would have been a certain improvement on the state of affairs, but an independent Tamil state would have been jettisoned. This was unacceptable to the LTTE, which had mastered the art of selling even a mirage as real.

The accord also came just four years after a Tamil-Sinhalese war, which until then had seen many cruelties from both sides and was yet to witness the barbarity that followed in the decades later. It would have been easier to overcome four years of bitterness and discord than what happened later. If the Sri Lankan state and the larger society had the vision, they could have acknowledged that 1987 marked a watershed in the sense the country would remain united while both sides would have to own up to the mistakes of the past (more true for Colombo) and try to live with one another as friends with adjustments.

The LTTE carried out its first suicide attack in July 1987. No such attack took place as long as the Indian military was there in Sri Lanka. Once the Indians departed, the LTTE transformed itself into a semi-fascist force that used brute power to put down all opposition, throwing to the wind all norms of democratic thinking and functioning. This, however, could last only till the Sinhalese side came up with their own version of an LTTE state, leaving Sri Lanka badly bruised and bloodied for posterity.

From the time the LTTE took on the Indian Army, it fought for 22 more years before its military annihilation. You could make that a quarter century if we add the 1983-87 period. After losing hundreds of thousands of Tamils, has the community gained anything tangible? Did the Sri Lankan state profit anyway by killing so many Tamils, a majority of them non-combatant civilians? Would Colombo have had to spend so much on the war if peace was accepted in 1987? The present mass suffering in Sri Lanka may have made ordinary Sinhalese feel bad the way successive governments treated Tamils, but will this regret materially change anything for scores of families on both sides of the ethnic divide who lost their sons and daughters to a brutal and senseless war?

Today, the shadow of the India-Sri Lanka agreement signed in 1987 may hold no hope even for many Tamils. But we witnessed how ordinary Tamils, sick and tired of four years of war from 1983, chased Indian Army trucks, offering coconut water and small eats to Indian soldiers who were fanning out in Jaffna. It is on the back of these innocent Tamils that the LTTE decided that war was the only way to Tamil salvation. The 1987 pact may or may have contained all the answers to the knotty ethnic row, but it could have been used as a base to build a better Sri Lanka.

MR Narayan Swamy is the former Executive Editor of IANS News Agency. He is the author of Tigers of Lanka (1994) and Inside an Elusive Mind (2003). Views expressed are the author’s own.