No less than 24 COVID-19 patients on life support died on April 21 due to a leak in a medical oxygen tank at the Zakir Hussain Hospital in Nashik, Maharashtra, which disrupted supply of the life-sustaining gas for at least half an hour. The high-level inquiry set up to ascertain if negligence caused the tragedy in the municipal hospital will presumably fix the blame, if at all, on one or more lowly scapegoats. Larger questions about the scandalous situation vis a vis supply of medical oxygen during the ongoing virulent and lethal second wave of the pandemic in India will likely remain unaddressed, especially at the official level.

It is significant that at least six High Courts have been dealing with complaints relating to management of the present surge in cases across the country. High Courts in Delhi and Maharashtra intervened this week to impress upon the Union government that it is ultimately responsible for ensuring oxygen supply during what is nothing short of a national health emergency, if not catastrophe. The judges’ exasperation at the evident procrastination and attempts to explain, even justify, the delay in requisitioning, diverting and distributing oxygen from industries – pending tardy imports – is clear from the uncommonly strong remarks made in court.

Justice Vipin Sanghi of the Delhi High Court went so far as to tell the government to “beg, borrow or steal” to ensure supply. The Nagpur bench of the Bombay High Court held an urgent sitting at 8pm to deal with the situation caused by a recent communication from the Union Ministry of Health and Family Welfare inexplicably reducing oxygen supply to Maharashtra, which has been consistently topping the list of the most coronavirus-affected states in the country, describing the move as “a bolt from the blue”. The court also took the government to task for not ensuring the fair and equitable distribution of the antiviral drug, Remdesivir, which has been widely used to treat COVID-19 in India.

On Thursday the Supreme Court of India initiated suo moto proceedings to consider four critical problems relating to the executive’s response to the pandemic, including its failure to ensure adequate supply of oxygen and essential drugs. In a sad reflection of the understandable erosion of faith in the highest court of the land in recent times, the move has been widely criticised by senior lawyers and others. The Supreme Court Bar Association (SCBA) has formally opposed the development in court.

Assurances by the government and industry that the country has adequate production capacity and stock of oxygen are not very convincing in the face of daily, distressing reports from various parts of the country of patients being turned away from hospitals that have run out of ICU and other beds equipped for oxygen therapy, and even of oxygen reserves. If there is a geographical mismatch between areas where supply exists and those where there is maximum demand, advance planning and preparation could surely have mitigated the problem.

It was clear from the early days of the pandemic that oxygen would be one of the most precious commodities in the battle against the virus and that efforts had to be made to not only augment supply but make medical oxygen readily available across the country. Unfortunately, the plan to install oxygen generation plants in district hospitals has evidently been a non-starter – not due to paucity of funds as much as other predictable but preventable reasons leading to unnecessary delays. A year down the line, citizens are paying the price for political and bureaucratic apathy and incompetence, especially at a time when there clearly is an acute shortage of commercial oxygen in many places.

The whole point of the abruptly imposed, severe, devastating two-month lockdown through the summer of 2020, when what now seems like a negligible 35,000 cases had been confirmed nationally, was to buy time for getting health systems ready for a possible surge in cases – and, presumably, for future waves of COVID-19 and/or other predicted pandemics. The gradual rise in COVID-19 cases during the first wave – up to the peak in mid-September 2020, when the active caseload was a little over 10 lakhs (1 million) – did not test the system as much as the current, continuing upsurge during which active cases have increased exponentially over just a few weeks to reach nearly 23 lakhs (2.3 million) on 22 April. India has now surpassed Brazil to become the country with the second highest number of coronavirus cases, after the United States. To make matters worse, there is ample reason to believe that the available data on prevalence and mortality may be more than just inaccurate, even purposely fudged, especially in certain states.

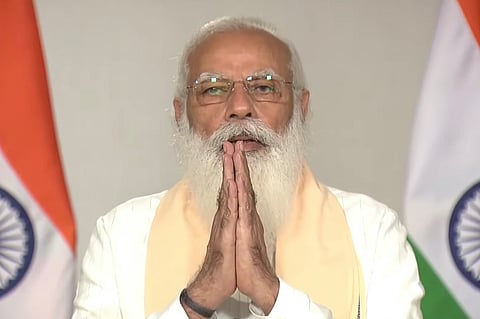

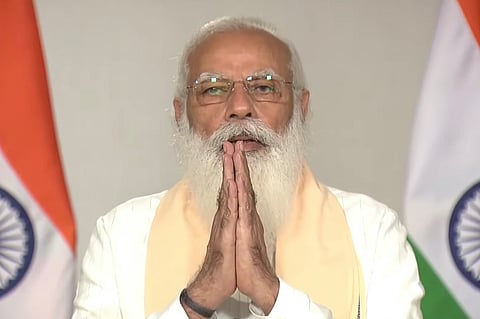

The vaccination story is another example of too little prudent and timely action too late. Despite all the delusional, self-congratulatory official rhetoric about the world’s largest and fastest vaccination programme – in the Prime Minister’s Mann ki Baat homilies (view/read the January and March 2021 monologues in particular) and elsewhere – the fact is that by April 20 a mere 8% of the country’s population had received the first dose of either of the two vaccines currently (barely) available in the country, and just over 1% had received the second dose. Even as acute vaccine shortage was being reported from many places, only partly due to restrictions on exports of key raw materials by the US and the European Union, the government decided to make vaccination available to everyone in the 18+ age group from May 1, bumping up the number of people eligible for vaccines to an estimated 800 million.

The powers that be appeared to wake up to the disastrous situation vis a vis vaccine supply and demand only in mid-April, in the midst of the escalating second wave. Mission COVID Suraksha to accelerate the development and production of “indigenous Covid vaccines” was launched on 16 April. Despite last minute efforts to approve Russia’s Sputnik V vaccine for manufacture in India, to fast track emergency approvals and import licenses for “videshi” vaccines authorised by western countries and Japan, waive import duty, speed up customs clearance and even allow states and private hospitals to directly procure vaccines, the situation is unlikely to improve much in the immediate future.

Things need not have come to such a grievous pass. According to a 2009 investigative report, India has had the potential capacity to produce adequate vaccines for any disease all along, with at least seven Public Sector Undertakings (PSUs) theoretically capable of manufacturing more than enough – not just for domestic use but also for the rest of the world, especially developing countries. Unfortunately, most of them have been rendered defunct over the years. New age “atmanirbhar” evidently does not take such unused, home-grown, public resources into account.

Needless to say, the size of India’s population is hardly a secret. To vaccinate three in five Indians, which the World Health Organisation (WHO) estimates will be needed to achieve herd immunity, the country reportedly requires 1.45 billion doses of vaccine by at least May 2022. It was surely obvious from the very beginning that two private companies alone could not be expected to fulfil such a huge in-country demand, let alone meet export obligations.

To make matters worse, the government evidently believed it did not need to consult the country’s national scientific taskforce on COVID-19: no meeting was convened in February or March, when signs of the impending crisis were clearly visible to genuine experts. In Karnataka, too, warnings from a technical advisory committee in November 2020 about an impending second wave in April-May 2021 were apparently ignored until it was too late.

Under the circumstances, the Prime Minister’s pious, platitudinous address to the nation on April 20, after weeks of silence on the rampaging virus, rang well and truly hollow – all the more so in view of the fact that he and/or the government he heads and the party he controls not only endorsed but participated in superspreader events, including massive election rallies, despite convincing evidence that the second, deadly wave of the pandemic was well and truly underway.