Education policy experts in the country have expressed a mixed range of opinions on the changes proposed to the school education structure in India as per the National Education Policy 2020 (NEP 2020). While a section of experts said that they understand the rationale behind the proposed changes, others have called it ‘impractical and illogical’.

The NEP 2020, released by the Union Ministry of Human Resource Development (MHRD), has sparked debates on various issues around the education system in the country and the changes the new policy proposes to introduce. The policy was drafted by a committee of experts led by Dr K Kasturirangan, the former chief of Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) and the former Chancellor of the Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU).

Among the important changes are the conversion of the existing school structure of 10+2 years to 5+3+3+4 years and the possible introduction of state-level school exams for students in Classes 3, 5 and 8 in addition to the exams already in place for those in Classes 10 and 12.

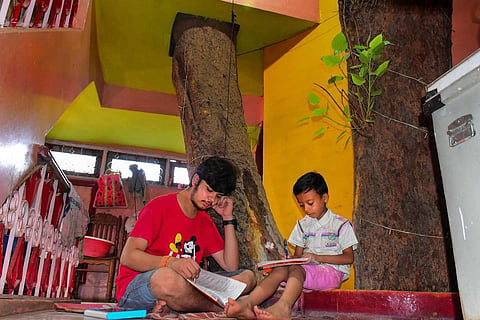

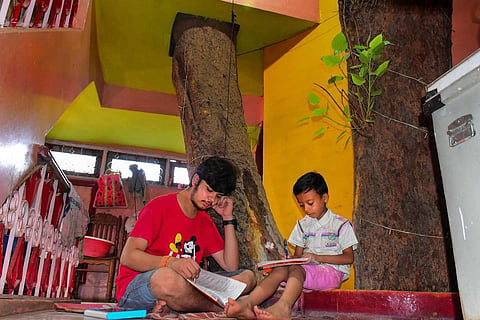

As per the new schooling structure, children aged between three and eight will be considered to be in the foundational level of education. Children aged between nine and 11 will be categorised as ‘preparatory level’, those between ages 12 and 14 will be categorised as ‘middle school’ level and those between 15 and 18 will be categorised as ‘high school’ level.

Welcoming the proposal to change the basic structure of school education in the country, BS Rishikesh, Associate Professor, Azim Premji School of Education, said that though there have been multiple changes in the pedagogy and curriculum over the years, the education structure currently followed in India is around 300 years old.

Stating that these five years (ages three to eight) would not be about teaching, Rishikesh pointed out that the aim was to strengthen the foundation of the child’s education. “Our understanding of how children learn has also evolved over the years. Brain development is fast in the early years of children between three and eight years old and hence this would be beneficial.”

“It is not going to be about getting the students do whatever they do currently in Class 1. It is more about getting their body movements in order, developing social skills, motor skills, etc,” he explained. He added that the structure is conducive to immerse the students in subjects from Class 6 onwards, since Classes 3-5 will now be devoted to ensuring basic literacy in language and numbers.

However, not everyone shares Rishikesh’s optimism on the proposal.

Anita Rampal, former Dean, Faculty of Education, University of Delhi, pointed out to TNM that in India, he early childhood education takes place under different modes and schemes like the anganwadis, which focus on nutrition to children more than education, or the kindergarten sections of private schools. Adding that the staff workers who are in charge of managing the balwadis and anganwadis might not be trained to handle the level of education the NEP 2020 expects, she said the focus should be on equipping teachers and workers.

“We need more intense and large-scale work to have professional development of teachers who tend to younger children. The younger the children, the more equipped the teachers need to be. How the government is planning to create opportunities for development of personnel is not mentioned in the policy,” she explained.

“The implementation, practicality and logic of why these changes are being proposed is not clear. We cannot just wish these things on a single line in the policy document and expect to change it immediately. There is no logic in putting Classes 1 and 2 with the early childhood Classes under the new structure,” Anita argued.

Another aspect of the NEP 2020 that has caught the attention of policy watchers is the introduction of vocational education as a part of mainstream education for school students. Anita Rampal pointed out that this might not translate on the ground as mentioned in the policy.

“It is important to have equitable education till class 10 for everyone. A lot of proposals specified in the policy have the potential to increase the gap between the under-privileged and the ones who have the resources and the social capital. For example, when the policy speaks about diverting students into vocational streams, it is the system that is going to judge the students based on its idea of ability. We know who will be sorted into the sought after academic courses through this and who will be marginalised into the 'skill' streams. These are not questions of choice as the policy claims,” she explained.

Anita also strongly opposed the idea of conducting common exams for students of Classes 3, 5 and 8, as proposed in the NEP 2020.

“We don’t need centralised assessment. Teachers are the best people to assess their students because they are the ones closest to them. I would rather suggest the government trust the teachers, develop their capacities to meaningfully tie assessment to the curriculum that is being transacted,” she said. The former Delhi University faculty added that it is crucial to have good teacher education programmes to enable teachers to bring about huge changes in the school education system.

However, Rishikesh said that assessment according to the policy could be beneficial as it could give some students more time to grasp certain things. For instance, “for a child in Class 3, the assessment could just be about language and basic arithmetic. If the student has not achieved the learning goals, the school can pay more attention to that in that year or in the next year. It need not be an assessment of performance of students.”

However, when asked if he feared that the proposed exams for Classes 3, 5 and 8 might turn out to be counter-productive, Rishikesh affirmed that the fear is real.

“Given the way society looks at education, the fear of these exams turning counter-productive to the cause is there. And therefore, I think a lot of effort needs to be put in by agencies such as the National Council for Education Research and Training (NCERT) and the Department of Education in every state to communicate about the exams. These are not performance evaluations for the kids but are just developmental metrics for the school, so that the gaps can be addressed in the school,” he said.