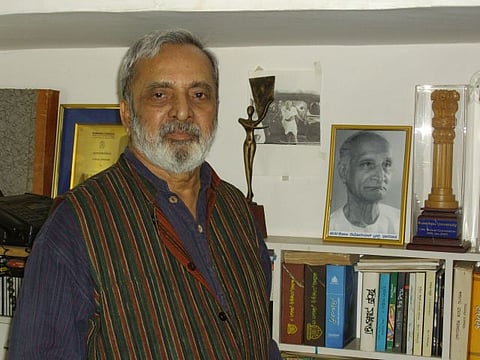

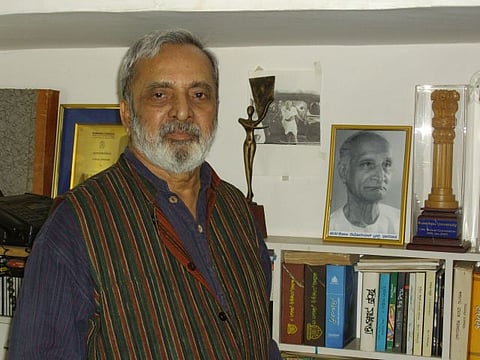

On August 22, 2014, Kannada literature lost one of its most eloquent writers. On the second anniversary of UR Ananthamurthy’s death, The News Minute has reproduced an extract from his last work, Hindutva or Hind Swaraj.

Towards the end of his life, Ananthamurthy faced the ire of many Hindutva supporters for his criticism of the RSS and also Prime Minister Narendra Modi. He wrote Hindutva or Hind Swaraj in response to his growing disquiet over a belligerent nationalism. Through aphorisms, history and fictional characters, Ananthamurthy mulls questions of good, evil, nationalism, Hindutva and also the actions of political parties. He concludes that Gandhi’s ideal of Hind Swaraj, or self-rule, had ceded ground to Hindutva, as advocated by Veer Savarkar in his book Essentials of Hindutva.

(Note: Raskolnikov is the protagonist of Russian writer Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s novel Crime and Punishment. Raskolnikov is a gifted student who kills two women. As the title suggests, the novel explores crime and punishment in the context of greatness, through Raskolnikov’s character and those of others.)

Godse and Savarkar aspired to a strong system with a mighty army. People like Modi live in a gumbaz, a dome that echoes what they say to themselves over and over again. This in itself is not new for India: the Congress leaders did that too.

Several writers and philosophers have been troubled as much by the fear of authoritarian rule as by the fear of anarchic rule. The great novelist Joseph Conrad was fascinated by the widespread anarchy in Poland but was also fearful of it. He found an environment where there were no restraints, no rules unbearable. His ideal was the British Merchant Navy. The harsh rules that the captain of a ship imposes on the crew are applicable to him as well. But within the rigid framework of these rules, there is freedom of creativity for each one. The ship has a life of her own. In English, a ship is referred to as ‘she’. Conrad is afraid that man may do whatever he pleases if there are no checks or restrictions on him. To all appearances a rightist, he is an author who believes that man’s hubris must not be given free rein.

Gandhi was able to reach his inner God, and heed His words in his fasts, in his silences and in his solitude. His last fast – where he ignored the material benefit to the country for whose freedom he had struggled – was at the behest of his conscience. With this fast he opposed Nehru and Patel, both dear to him. This was possible because of divine grace.

(Hindutva or Hind Swaraj was published in English by Harper Perennial in 2016.)