When I think of science fiction films I watched growing up, there are not many Indian films that come to mind except perhaps Koi Mill Gaya, which many have pointed out was loosely based on the Hollywood classic E.T. Even Koi Mill Gaya was a far too Bollywood-ised version of an alien-human friendship fantasy story, with little science and a lot of fiction.

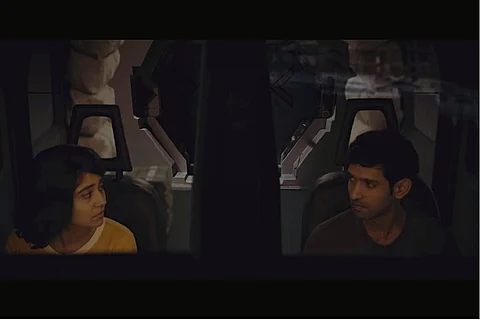

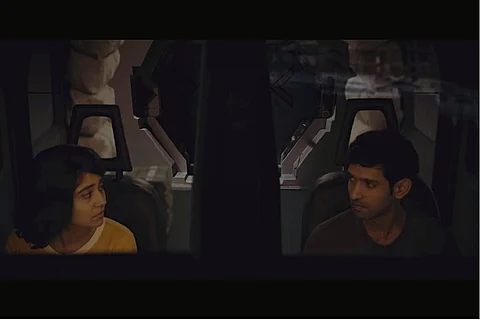

However, watching Cargo felt different. The Arati Kadav directorial which Netflix picked up was also screened at the Mumbai International Film Festival (MAMI). Starring Vikrant Massey and Shweta Tripathi, the film is set in a world where humans and rakshasas (demons in Indian mythology) have reached a peace agreement, where in rakshasas run the Post-Death Transition Services in spaceships called ‘Pushpak’ where the dead are sent. Here’s the rakshasas – who look nothing like their terrifying blood-lusting depictions in mythology – methodically heal the bodies of the dead, talk to them gently, wipe their memory and send them to their next life.

What sets Cargo apart when it comes to sci-fi in Indian cinema is that it is very rooted in the Indian context, and yet it does not lose out of the existentialism and fictional-but-close-enough-to-be-a-possibility quality that many science fiction films bring to the screen.

For one, when we see people come onto Pushpak 634A, where Prashasta (Vikrant) has been staying by himself and sending people for reincarnations for decades, the transience as well as the largeness of life are juxtaposed all at once. Reincarnation or the thought of having a good life continues to drive ways of life in India till date. Lessons are handed down since we are children to do good and be good based on the belief that we are answerable to a larger power, or for the fear of suffering that will come our way based on the next life. However, when one man reaches Pushpak 634A after being stabbed to death by his brother, he rues that what will be the difference between him and his brother if there is no heaven or hell, if his brother will also come to one of these spaceships and then be reincarnated.

On the other hand, a man – a groom-to-be who dies in an accident – requests Yuvishka (Shweta), who comes to work as Prashasta’s assistant, that he be allowed to make a phone call to Earth to tell his wife-to-be to move on and remarry. A sentimental Yuvishka allows him to do so, which is against the rules. However, it turns out that the man called the woman and told her if she remarries, he will haunt her husband.

In several juxtapositions like this, Cargo brings out just how transient life can be, how futile our attempts to hold on to it, to things – belongings that the people who come to Pushpak have to leave behind in a tray – are. On the other hand, each life is also meaningful on its own, capable of affecting so many others, in life and in death. All the people who die and come to the Pushpak ships are referred to merely as ‘cargo’ – a dehumanising word – and yet when they come to the ship, in many ways their desires to hold on to life are both comical because of their futility and yet so poignantly human.

Even Yuvishka and Prahasta’s desire to not be forgotten, to be remembered on their terms is shown with sensitivity and care. In fact, Prahasta’s isolation on board the Pushpak 634A for decades is oddly reminiscent of present times where we have spent months being confined to our homes, communicating with people through screens. His hesitation to retire and return to Earth despite having spent about 75 years on the spaceship is also indicative of how, as people, we learn to cope and resist change even though it seems for the better. However, the cycle of life must go on – and we see this as Prahasta’s ‘cargoes’ start repeating, recognising him, even as he realises it’s time for him to let go of his charge… for Yuvishka to take over in his stead.

It is also quite interesting how Cargo turned mythology with its black-and-white demarcation of rakshasas as evil, ugly and deceitful on its head. In this film, Surpanakha (Ravana’s sister) and Ghatotkacha (the demon who was Bhima’s son in Mahabharata) are normalised as the names of a pop star and Yuvishka’s younger brother. They are shown as a part of the society, persons with a humanity of their own, albeit with some special powers. The vilification of rakshasas as dark and dangerous beasts in Indian mythology has been called casteist in some subaltern interpretations and texts, so to see Cargo turn it on its head is refreshing. Although, it is the rakshasas who end up dealing with the dead in this world too.

In many ways, Cargo feels like a film that will be remembered in the Indian sci-fi scene. It is not an edge-of-the-seat, action packed thriller at all, but it is so uniquely rooted in the Indian culture, myths and stories, and yet it subverts them with a subtlety that make it easy to accept. Cargo is a sign that Indian cinema can bring exceptional contexts into science fiction cinema, and hopefully, we will have more filmmakers exploring the same.