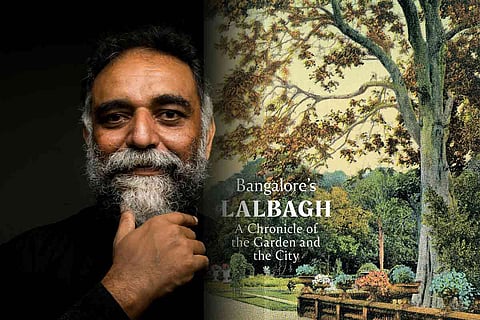

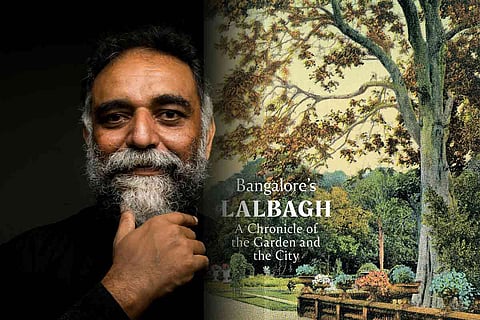

On Wednesday, September 22, artist and author Jayaram Suresh launched his book Bangalore’s Lalbagh – A Chronicle of the Garden and the City, an in depth history on the city’s beloved botanical garden. In an interview with Susheela Nair for TNM, Jayaram, who is also an art historian, curator and founding director of the 1Shanthi Road Studio/Gallery, talks about how he went about collecting, collating and documenting the history of Lalbagh, and its connection to the city.

I am a diehard Bengalurean— this city and its gardens are my muse. I have been archiving the city for the last two decades as an art historian and curator interested in anthropology, urbanism, heritage, people, and living traditions. I have collected and curated this material into a resource that has been a repository of a project called ‘Mapping Bangalore’ and for other projects like the Srishti School of Art and Design and the India Foundation for the Arts grant on Project 560, relating to the multiple narratives of the city through the landscape, people, food, postcards, landscape, and representation of the city through photography.

The process involved extensive archival research from public and private collections, leading me to government documents, books, personal albums, and oral narratives. Also involved, was research around maps, images, illustrations, photographs and botanical drawings from the Karnataka Horticulture Department. The book also maps my family’s connection to the garden and narratives based on the city’s social and historical context.

My fascination for the green spaces of Bengaluru — Lalbagh and Cubbon Park — has long been a romantic obsession from my childhood, it has influenced my life and work as an artist and writer. My association with nature in the urban context and my documentation of culture became a repository of images and text. About three years ago, a friend of mine, Mohan Narayanan, who walks with me in Lalbagh nudged me to put this together as a book and share our common love of this garden.

It is a privilege to live in Shanthinagar, a centrally located area that connects Cubbon Park and Lalbagh, and share with others my knowledge. 1Shanthiroad Studio, my house has become an art space — an open house and a hub for creative people. My archive of this city has become a resource for me and many others who live and work here. The first documents of Lalbagh that I came across were from my family album. I also sourced from other archives like the Lalbagh Library, friends like Harish Padmanabha (an art collector), who has a good collection of HC Javaraya's (one of the architects of Lalbagh) history, the photo archive of Aliya Krumbiegal and Clare Arni's collection of old postcards.

Lalbagh is very rich in history. It has prehistoric rocks, ancient archeological remains like ‘veeragallu’ or hero stones, Kempegowda's watchtower, and the Sultan’s garden for Hyder Ali and Tipu Sultan. It was also the site of British colonial enterprise, and was also used by the Mysuru princely state for horticulture development and to drive its modernist agenda.

The book started with personal narratives, then historical incidents, local narratives, and reference to accounts of other travelers like Francis Buchanan. It is like a collage of anthropology, art history, and urbanism.

Hyder Ali and Tipu Sultan played a significant role in the horticulture of the region during the 18th century, by creating many baghs or gardens in the city. They imported exotic plants from different regions and had also sent Dervish Khan, an ambassador to the court of Louis XVI in France, to bring back characteristic fruits and flowers of Europe, along with a gardener to tend to these plants. This is unique botanical diplomacy that was visionary.

People like John Cameron, GH Krumbiegel, HC Javaraya and MH Mari Gowda played a significant role in the development of Lalbagh in distinct ways, including plant introduction, the building of monuments, the expansion of Lalbagh, and taking horticulture to different parts of the country.

My childhood was filled with outings to Lalbagh and other gardens in the city. I enjoyed climbing trees, plucking mangoes, playing hide-and-seek, and feeding the deer in Lalbagh. We also had picnics expeditions for specimen collection. This place was like a jungle and ‘garden of earthly delight’ — my book of nature and I discovered all sorts of plants, insects and birds, all in one place. It made me sensitive to nature.

My grandmother, who lived in Mavalli next to Lalbagh, narrated stories about orchards and thotas (plantations) and mentioned the famous Bengaluru apple (which used to flourish in the city). This triggered my curiosity to find this elusive tree that was lost in this urban maze. The interest in the community of gardeners, the Thigala community, is part of my family's lost heritage. A keen study of their folk rituals like the 'Karaga Jatre' and meeting many farmers and gardeners from the community made my research more rooted in the city’s native soil and its cultural context. It is here that I rediscovered my identity as part of the Thigala community and pieced it together with history, time, memory, aspiration and loss, to seek myself in this multiplicity.

Lalbagh is not only a visual treat for visitors to the city or regular morning walkers or joggers. It is a trail of scents from various leaves and flowers-- like the fragrant eucalyptus, the heavenly scent of the Champa and Sampige, the exotic ylang-ylang. It is a birdwatcher’s paradise and, above all, my spiritual real estate. This is how I have concluded my book: “This garden in the middle of the city is a paradise; a resort for the community, temple of the mind, spa for the body, and clinic for the soul. It is here that we can safely place our hope when all else is lost.”

Susheela Nair is an independent food, travel and lifestyle writer and photographer contributing articles, content and images to several national publications besides organising seminars and photo exhibitions. Her writings span a wide spectrum which also includes travel portals and guide books, brochures and coffee table books.