In pre-pandemic times, a typical Sunday morning visit to Lalbagh, Bengaluru, will have you witness scores of people taking brisk morning walks around the lake, old friends catching up with each other while sitting on the benches, groups of avid bird-watchers with binoculars around their necks. While there is a lot to appreciate about Lalbagh — from its rare varieties of flora to the large number of birds that frequent the place — the park has a fascinating history. Hyder Ali ordered the construction of Lalbagh in the 1760s, and the project was later finished by his son Tipu Sultan. The 30-acre expanse was modeled around places like the Mughal Gardens in Delhi and Sira, Karnataka. However, the history of Lalbagh dates back to millenia before 1760.

The large rock that one can see near the East or main gate of Lalbagh is one of the oldest in the world. The Peninsular Gneiss, as it is referred to, is close to three billion years old. The rock, which was declared as a National Geological Monument by the Geological Survey of India, has been the site for research conducted by those studying geology and evolution all over the world. In his book Lalbagh: Sultan’s Garden to Public Park, naturalist Vijay Thiruvady, who also conducts the Bangalore Walks programmes, says that the Peninsular Gneiss has witnessed human settlement from as far back as 3000 BC, and that evidence of Megalithic humans was found inside Lalbagh’s premises. However, after the artefacts were transferred to the Government Museum, the site was levelled out and unfortunately cannot be seen today. The hillock also houses one of four watchtowers said to be erected by Kempegowda, the founder of modern-day Bengaluru, in the 16th century when the city was built. The popular belief is that the structures were built in four corners, and if the city were to grow beyond the boundaries, it would fall to ruin. But though uncontrolled expansion does plague the city today, it is not necessarily due to Kempegowda’s ‘curse’.

Kempegowda's watchtower atop the Pensinsular Gneiss | MP Narahari

Another piece of history is hidden away inside Lalbagh, which often goes unnoticed by visitors. These are 'hero stones' or veeragallus, which detail stories of warriors who died in battle. Hero stones can be found across India, and some date back to 500 years while others are as old as 1500 years. There are two such hero stones in Lalbagh — one near the Peninsular Gneiss, which is estimated to be from the 10th century, and the other near the Horticultural Office, estimated to be from the 13th century, inside the park premises. Though it is not clear whom the hero stones refer to or who built them, they offer a glimpse into Bengaluru’s medieval history.

The 'veeragallu' or hero stone near the Horticultural Department | MP Narahari

While Hyder Ali and Tipu Sultan envisaged Lalbagh merely as a garden, when the British took over the administration of the place after 1799, they started to expand it, and made Lalbagh into the 240-acre expanse that it is today. They also started to import several species of trees from far-off colonies, like the Baobab tree from South Africa, which thrive in an environment completely foreign to their natural habitats. Apart from Lalbagh, several of these species do not exist anywhere else in India. Other than the exotic plant species, several indigenous species like the silk-cotton tree, varieties of fig and jacarandas are abundant here. These attract scores of birds of all sizes — from the migratory ashy drongo to the majestic purple heron, eagles, owls and ducks. This makes the park a haven for nature enthusiasts and bird watchers, and groups offering tours on the nature and history of Lalbagh on weekends.

The Baobab tree in Lalbagh | MP Narahari

Another lesser-known fact about the park is that, for a brief period of time in the 1860s, Lalbagh housed a menagerie of animals such as tigers, gibbons and even rhinoceros, apart from smaller birds and animals.

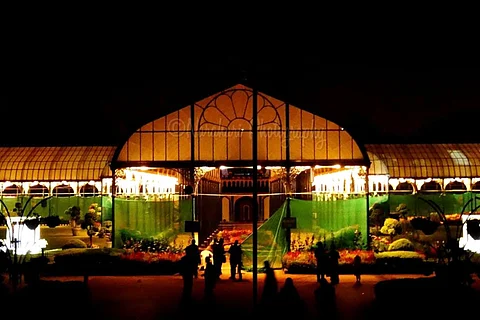

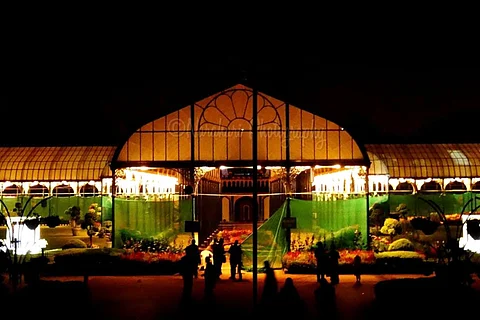

When the British took over the administration of Lalbagh, they not only expanded its horticultural collection, but also built various structures inside. A landmark of Lalbagh is the Glass House, where the two annual Flower Shows are held. Modelled around the Crystal Palace in London, the Glass House was built in 1889 in honour of Prince Albert Victor, grandson of Queen Victoria. It was one of the first few prefabricated structures in India, which means that it was built in Glasgow and assembled in Bengaluru. The Glass House is one of the most iconic structures of the city, and was always meant as a symbol of grand luxury.

The iconic Glass House of Lalbagh | MP Narahari

“We hear a lot of people parrot the line that there is nothing to see in Bengaluru and that it is a new city. These hero stones and monuments prove that there is a lot to see, cherish and preserve in our Bengaluru, and we should be proud of our rich history,” says MP Narahari of Peek Into Nature, a venture which offers history and ecological tours of Lalbagh.

To learn more about Lalbagh’s ecology and history, contact MP Narahari (+91 9844794018) of Peek Into Nature for a tour.