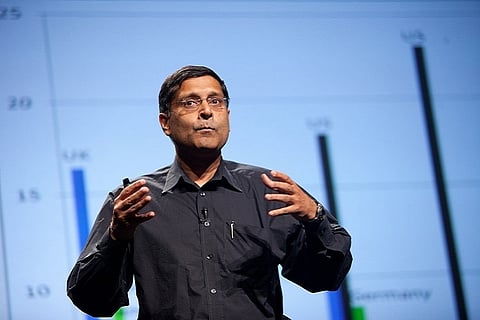

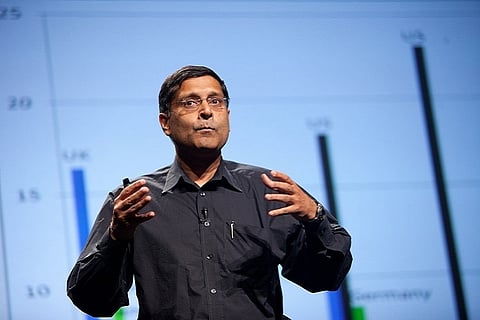

India may not be the ‘fastest growing economy’ in the world after all. A study by India’s former Chief Economic Adviser Arvind Subramanian says that the real gross domestic product (GDP) growth of the country may have been overestimated between 2011-2017. According to his research paper published by the Center for International Development at Harvard University, the growth was actually only 4.5%, as against the reported growth of 7%

How did this happen?

From 2011-12, India changed the methodology and data sources used to estimate real GDP of the country. Earlier, while data was derived from the factory level, it was changed to 5 lakh companies registered with Ministry of Corporate Affairs (MCA). Apart from that, while GDP measurement was calculated via factor costs, it was changed to calculating via market costs. What this means is that while earlier GDP was measured based on cost of production that producers or service providers incur after removing the effect of indirect taxes or subsidies, it was shifted to calculating by measuring the actual expenditure incurred by consumers including any subsidies such as food and petrol provided to them.

At the time, this move was welcomed as it was said to be more in line with global practices and gave a better picture of economic activity.

However, the research paper by Arvind shows that this change has led to a significant overestimation of growth.

“Official estimates place annual average GDP growth between 2011-12 and 2016-17 at about 7 percent. We estimate that actual growth may have been about 4.5 percent with a 95 percent confidence interval of 3.5 - 5.5 percent,” the paper states.

His paper says that the change in methodology made the GDP estimates more sensitive to price changes at a time when oil prices were falling. The new methodology deflated the value of input values by output prices, which overstated manufacturing growth. This, therefore, affected the measurement of the formal manufacturing sector.

So, what does this mean?

“The Indian policy automobile has been navigated with a faulty or even broken speedometer,” he says in the report.

Arvind says that in the last few years, the focus of the country has been on employment and agriculture and the financial stress in the corporate sector and low capacity utilisation. These issues were seen as anomalies despite ‘good growth’ when in reality, they may have partly stemmed from weaker-than-believed growth.

The overestimation of growth is a critical matter for internal policymaking, Arvind says. And being misled about the health of the economy influences the impetus for reform in serious ways. Had the growth been what Arvind’s estimates show, policy action could have been a lot different. The interest rate too, which is usually lowered or increased based on the economic state of the country, may have been too high, by as much as 150 basis points.

“For example, if India’s GDP growth had been appropriately measured, the urgency to act on the banking system challenges or agriculture or unemployment could have been very different. It is understandable when policy makers favour the status quo if that status quo is apparently delivering the fastest growth rate of any major economy in the world. But if growth is actually 4.5 percent instead of 7 percent, attitudes to policy action should and would be very different,” he says in the paper.

What can be done now?

Arvind’s paper says that growth must be restored as a key policy objective.

“Going forward, there must be both the urgency from the new knowledge that growth is weaker-than-believed and the re-embrace of growth as necessary to accomplish other objectives,” the paper says.

He says that India must restore the reputational damage suffered to data generation in India across the board—from GDP to employment to government accounts.

This, he believes, can be done by appointing people with stellar technical and personal reputations.

He also says that the entire methodology and implementation for GDP estimation must be revisited by an independent task force, comprising both national and international experts, with impeccable technical credentials and demonstrable stature.

Is the overestimation political?

Arvind stresses in his paper that the overestimation is not political.

The change in GDP estimation methodology was initiated by the UPA-2 government, as part of the changes that routinely occur with base revisions to GDP estimates.

The work was carried out by statisticians and technocrats and only completed in late 2014, which was after the NDA-2 government came into power.

“But since they affected GDP estimates beginning in 2011-12, the revised numbers spanned the period of both governments. The non-partisan nature of the exercise is suggested by the fact that the new estimates bumped up significantly the growth numbers for 2013-14, the last year of the UPA-2 government. Today, these changes are being seen as political because of other controversies that have arisen that, in principle, must be distinguished from the methodological change,” the paper states.