Mobile Pragya is plump with smooth, dark skin, and like many sex workers in Mysore looks like any other middle-class woman. She has strikingly white teeth, and one tooth in front is slightly crooked, giving her a permanently mischievous look. Her eyes have a certain sparkle and she is prone to laughing as she talks, especially when she gets to the grimmer parts of her tale. She radiates confidence and charisma. She speaks in a rush, and I need to cut her off at times, to let KT do the translation, and to interject a question.

‘My name is Mobile Pragya, but I’ll tell you later why that name. In those days boyfriends used to beat us if we didn’t bring them enough money in the evening. They would say, “Oh-ho, you have got another boyfriend, is it?” This was the situation for all of us. The rowdies would take us away by force, keep us locked in the house for a few days. Sometimes if the policemen saw us in the field they picked us up. They would abuse us in the police station. In those days I hated all men, because I thought all men would approach me only for one reason, to have sex.

‘Once I was arrested along with some women. We were in the lockup, all waiting for the worst things to start. Before anything could happen, a nice man came with a card and we were released. I had been hearing about this new project, and how they gave women a card and no one bothered them. I decided that I also must get a card.’

The deputy commissioner of police (DCP) for Mysore, Vipin Gopalakrishnan, had rounded up all the sex workers his force could find in the city and thrown them in jail, before his meeting with Sushena. He had thought she was from some highly connected organization that was out to end sex work. Before she could speak he said, ‘Madam, I can’t lock these women up every time you come here. They too are people. It is not fair.’ Sushena explained that she too didn’t want sex workers put in jail, and that she was from a programme that worked to keep sex workers and the public safe from HIV. When she introduced the two women with her as sex workers, he looked surprised that they both could come and sit confidently before him.

The DCP offered tea and asked a lot of questions. His expression darkened as he learnt of the extent of violence that the sex workers of Mysore faced from the police. Suddenly, he put up his hand, and stopped Sushena mid-sentence. He called in his aide and gave orders that identity cards should be issued immediately to every worker on the Ashodaya programme – and he would personally sign each card. Sushena told him, praying he wouldn’t take back his decision, that many of those workers were in fact active sex workers. He said it didn’t matter. The incident again proved what I had discovered throughout my time with Avahan – that a single good person in a position of authority could make a big change in an otherwise rotten system. Gopalakrishnan’s support, in the form of a simple card, did not end all police violence or stop them from looking away when it happened. But it was a huge message – that sex workers are also citizens with rights. It was an incentive for people like Mobile Pragya to join the programme in huge numbers. The sex workers who were given identity cards were highly protective of their cards. They recorded every incidence of violence and gave a monthly report to the police.

Mobile Pragya continues: ‘Those days I used to go to Lalitha Lodge at ten in the morning and go back home by five. It was like my office,’ she says laughing. ‘Sometimes the police would come around eight-thirty at night and arrest all the girls in the lodge. At that time, I had a mobile phone and so the lodge people used to call me Mobile Pragya. I was the only such person with a phone. When the police raided they would arrest everyone but not me. There was a feeling that since I had a mobile I must be having contacts. I started being well known for that.’

One day the Lalitha Lodge owner got a message that the sub-inspector of police wanted to see ‘Mobile Pragya’ at the police station. There Mobile Pragya was accused of running a sex racket and given a severe beating. She says she wasn’t sexually assaulted but that everyone, down to the cleaning person, took turns beating her. She was locked up for two days, then released. It was the breaking point for her.

She says, ‘At that time, they were giving identity cards to the women who were working on the project. Those who had the card were never arrested. I went to the office and asked for the card and I was told to first go for a health check-up. I went three or four times to the office, and volunteered to do some work, and they gave a card to me.’

Now that she had what she wanted, Mobile Pragya escaped into the field, and for almost two months the programme staff couldn’t find her. When they did eventually they assured her they didn’t want the card back. Listing out her skills, they told her she should start putting them to use in Ashodaya. They praised the way she presented herself well and her confident manner of speaking. Mobile Pragya in all her life had never received appreciation for anything. She decided to give it a shot and joined Ashodaya as a member of its enabling environment team, which was engaged in crisis response.

Mobile Pragya soon became the lead member of the team. Her job was to go to the court, explain the Ashodaya programme, and secure the release of sex workers who had been arrested. Fearful at first, she finally developed the courage to go to the same police station where she had been beaten for days to negotiate directly with the police. Her status with the police was markedly different when she presented herself as a confident, card-carrying member of Ashodaya.

Mobile Pragya says, ‘I learnt from the project that to do sex work itself was not a crime. I understood what the law says about how to arrest women.’

Mobile Pragya continues: ‘One day the DCP said, go and talk to the street-level police, train them on the procedures. This DCP had already visited our programme.3 Once a murder had happened and some sex workers had been picked up. They had been in jail for three months. The inspector came to my house to discuss the situation with me and asked me how we could approach the case.’

Mobile Pragya had started working with and for the police, rather than being their victim. She had earned her Ashodaya card.

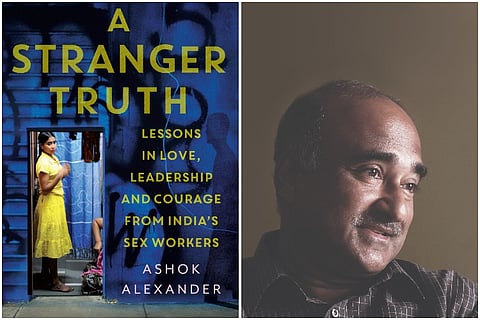

Excerpted with the permission of Juggernaut Books from the book 'A Stranger Truth: Lessons in Love, leadership and Courage from India’s Sex Workers' by Ashok Alexander. You can buy the book here.