Trigger Warning: This article contains details of sexual assault, which may be triggering for some.

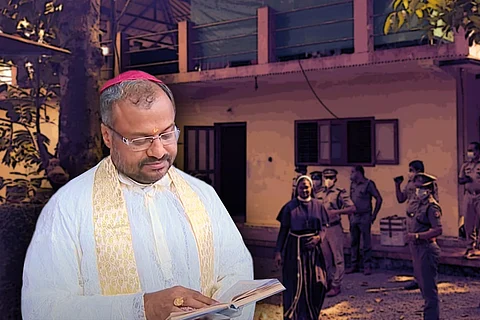

The Additional Sessions Court in Kerala’s Kottayam district established the relationship between Bishop Franco Mulakkal and the nun who accused him of raping her — a fiduciary relationship. Inherently, in a fiduciary relationship — for example, doctor-patient, parent-child, or church-parishioners — one person, called the fiduciary, is in a position of leadership within an institution and is obliged to act in the best interest of the other person, the beneficiary. The scope of this relationship is founded on trust between the two entities/individuals; power of the fiduciary; and confidence or reliance of the beneficiary in the fiduciary’s discretionary power. By virtue of the fiduciary holding certain powers, primarily administrative ones, the beneficiary is peculiarly placed in a vulnerable position in this alliance.

In Franco’s acquittal judgment, Additional Sessions Judge I Gopakumar G acknowledged the power dynamics between the bishop and the nun. However, the court brushed aside this crucial lens to understand the nature of the sexual violence that the survivor brought before the justice system, and attempted to explain. The judge, instead, built his verdict on the survivor’s inconsistencies in her statements, her inability to articulate the sexual crime, her failure to disclose penile penetration during medical examination, in-fighting in the convent, and a disproved illicit relationship, among others. The possible psychological and social forces dictating the allegations were disregarded, thereby disbelieving the survivor.

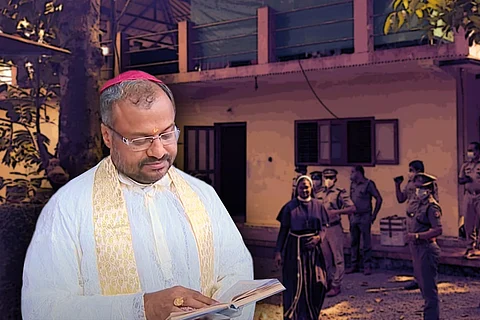

The survivor nun is part of the Missionaries of Jesus (MJ) congregation, residing at one of its three convents in Kerala, in Kottayam’s Kuravilangad. The principal seat (or office) of the MJ congregation is Jalandhar in Punjab, of which Franco Mulakkal is the bishop. The defence had contended that Franco Mulakkal is not the Supreme Head of the diocese to have a fiduciary relationship with the nun. The court, however, relied on documentary and oral evidence to conclude that Franco Mulakkal, the bishop of the Jalandhar diocese, is indeed the supreme authority, who exercises power over the administrative and disciplinary matters of the MJ congregation and its convents.

The court even touched upon the widely-discussed, menacing characteristic of a fiduciary relationship — the vulnerability or the dominant-subordinate nature. “... All religious heads draw power on their subordinates on the strength of their positions as head of the institution,” it said.

The judge also drew on certain provisions of the Indian Penal Code (IPC) to contextualise the interpretation of “authority.”

However, a contention still hanged heavy over the case: Did Bishop Franco misuse his position and fiduciary relationship, and commit “sexual intercourse with the nun repeatedly”? It must be noted that IPC section 376C deals with sexual intercourse by a person in a position of authority or in a fiduciary relationship, and that only one instance of rape or sexual assault needs to be proved in court.

Franco Mulakkal was ordained as the Bishop of Jalandhar in August 2013, two months after the survivor took charge as the Mother Superior of St Francis Mission Home, the Kuravilangad convent of the MJ congregation. With the permission of Sister Regina, the then Mother General of the MJ congregation, the survivor started the renovation work of the convent kitchen.

According to the survivor, Bishop Franco controlled the renovation and construction works in the convent, and in November 2013, he asked her to stop the work for an inspection. In January 2015, he allowed her to continue the renovation.

Before Franco reached Kerala on May 5, 2014, to attend the ordination ceremony of a priest, he had informed the Mother Superior of the convent, the survivor, that he would be staying at the convent that night. On arriving, the survivor and another nun had to carry his luggage to his room, and even iron his cassock for him — an example of the superior-subordinate relationship within the church.

Later that night, Franco asked the survivor to bring the papers for the kitchen work to his room, where, for the first time, he sexually assaulted her. He then allegedly threatened her with dire consequences if she revealed the incident to anyone.

This was the first instance of breach of trust that a fiduciary relationship fundamentally demands.

“The bishop was like god to her. She had placed him in her father’s place. She didn’t expect such a person to abuse her sexually,” read the judgment.

Franco allegedly continued to exploit his power of position, forcing her to come to his room whenever he visited the convent. The survivor, fearing consequences and threats to her family, yielded. She was sexually assaulted on 12 more occasions.

She managed to confide in her “spiritual mother” Sister Lissy Vadakel of another congregation, as well as a local priest. Both asked her not to reveal the incident fearing expulsion from the convent as she had taken the vow of chastity.

Each time he visited and stayed at the convent, Franco informed the survivor, as she was the chief of the convent. In December 2016, when he informed her of his arrival again, she threatened to go stay at her house. He stopped coming to the convent thereafter, though he allegedly continued to message her.

The nun who took the vow of obedience, said no to a bishop, disobeying a man who was in a position of dominance over her. With that bold move, however, consequences ensued. In December 2016, the survivor was accused by her cousin of having an illicit affair with the former’s husband. She was subjected to internal enquiry, including victim shaming, on the alleged orders of Franco.

In January 2017, she was removed from the position of Mother Superior of the convent. The survivor understood that, from now on, Franco need not inform his arrival to her, as she was an ordinary nun at the convent, said the judgment.

As the fiduciary, Bishop Franco’s duty extends to all nuns in the congregation. However, he allegedly wielded his power as the authority of the congregation to issue transfer orders, and internal inquiries based on certain complaints on the survivor and the nuns who supported her.

On multiple occasions, the survivor complained of retaliatory steps for not yielding to Franco’s sexual advances. Her fellow nuns, too, complained of retaliatory measures for supporting the survivor.

However, the court failed to place these allegations against the backdrop of the rampant abuse of power within the highly hierarchical and structured organisation of the Church, where allegations against revered religious figures are shrouded in silence, threats and cover-ups.

In a Boston Globe article titled Abuse in the Catholic Church, Mathew Schmalz, director of Asian Studies at the College of the Holy Cross in Worcester, argued that in India, such abuse of power fizzles out as mere rumours and gossips. “It never reaches the level of formal charges or controversies,'' said Schmalz, who has researched Catholicism in Asia.

This could be sampled in the court’s verdict, which unduly hinged on vacuous points — the complaint of “illicit relationship” filed by the survivor’s cousin Meena (name changed); the survivor’s inability to explicitly tell her fellow nuns and in complaints that she was raped on 13 occasions (the court pointed she said “facing retaliatory measures for not sharing bed with him” instead of saying raped or sexually abused); the indiscipline within the congregation.

By disregarding more pertinent points, the court foundered, to start the much-needed conversation on the power imbalance within the church — between a bishop who wields remarkable control over the church and the nuns who are subordinates trained to yield to orders without question; and between the bishop/priests and the parishioners who are at the mercy of the discretionary power of the former.

It fell short of being a landmark judgment for the women in the Christian community, and more importantly, a talking point in the fight for gender equality and against workplace sexual harassment. As the judge in the Priya Ramani verdict observed, "Even a man of social status can be a sexual harasser," and that “a woman has right to put her grievance even after decades.”

Referring to a 2009 Tamil Nadu case, the Kottayam additional sessions court equated evidence and allegations in the Franco case with “grain and chaff inextricably mixed.” It said that it was not feasible to separate truth from falsehood. And so, “the only available course is to discard the evidence in toto,” the judge said, winding up its verdict acquitting Bishop Franco Mulakkal.

Watch: Franco judgment inhuman, insensitive and accused-biased - A discussion