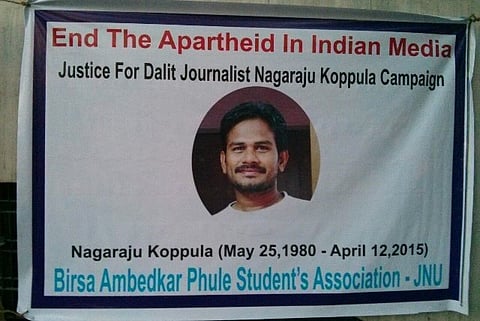

In 1996, when B K Uniyal went through the names of 700 accredited journalists in Delhi, he couldn’t identify a single Dalit among them. He realized that not once in his 30 years in the profession had he met a Dalit journalist. In 2013, Ajaz Ashraf found 21 across the country. On April 12, 2015, that tiny number shrunk even further with the death of Koppula Nagaraju, a reporter with the New Indian Express Hyderabad, triggering protests and condemnation.

Nagaraju (34) died of cancer, but it wasn’t just the disease which made his death painful. His friends allege that he was discriminated against because of his caste, and that in his final days he got no support from his organization or senior editors.

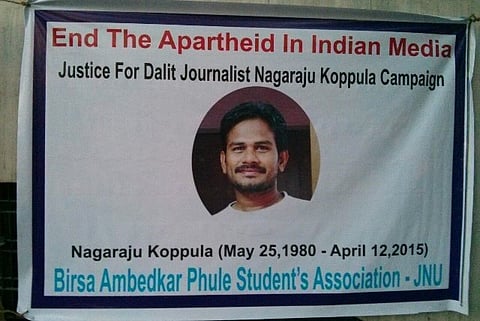

Along with journalists’ associations like the Telangana Union of Working Journalists and the Delhi Union of Journalists (DUJ), Nagaraju’s friends have organized protests in many cities, demanding justice. At a condolence meeting in Delhi on April 23, the DUJ “resolved to fight for justice against the casteist discrimination and contractual exploitation meted out to him by his employers… (who) underpaid him, denied health benefits… Provident Fund and other monetary rights pushing him to death”. These allegations have once again brought the lack of diversity in Indian newsrooms to the fore.

Independent journalist Paranjoy Guha Thakurtha, a former mentor of Nagaraju, participating at the condolence meeting organised by the Delhi Union of Journalists.

Hailing from Sarapaka village in Khammam district, Nagaraju was the first person from the Madiga community to become a journalist for an English newspaper. The youngest of five children, Nagaraju worked as a construction labourer, sold ice cream and painted sign boards to complete his schooling after his father’s death, when he was just four years old. Armed with a diploma from the Indian Institute of Journalism and New Media in Bengaluru and an MA in History from the University of Hyderabad, Nagaraju landed a job with the Hyderabad bureau of The New Indian Express in April 2011.

Nagaraju was not a press conference journalist – a term which would be understood by the journalistic fraternity to mean someone who did not do stories merely to fill the pages of the newspaper. A friend and Hyderabad-based journalist Swati Vadlamudi recalls that on many days, Nagaraju would file several stories with multiple bylines. “Filing four stories with bylines in a day is not a joke,” she says, adding that he would often take a nap on a park bench or traffic island in between stories and assignments.

He covered everything from turtles to prisoners. His stories include those about prisoners turning doctors for their fellow inmates, living conditions in mental health institutions, prisoners dying due to poor medical care, tortoises turning gay, a mentally ill HIV+ child.

However, all this abruptly came to an end in October 2012 when he was forced to take leave without pay to recover from Tuberculosis. But five months later, tests revealed that he actually had lung cancer.

“Nagaraju did not die because of cancer. He died as a result of sustained and systematic casteist discrimination that pushed him into a corner, and which forced him to seek cheaper medical attention that resulted in him being misdiagnosed with TB. This caused a five-month delay in his treatment for cancer,” says his friend and former journalist Chittibabu Padavala.

A protest outside The New Indian Express office in Hyderabad organised by the Telangana Union of Working Journalists, Telangana Azad Force and other groups including Dalit organizations

A year after he joined, when he finally got his increment, he felt it was too low and raised the issue with his editor. “When he raised the issue with his Resident Editor, Nagaraju told me that he was rudely ushered out of the RE’s chamber. The RE had also announced in the office that when people ‘act smart’ their bylines should be reduced. If the newspaper conducts an inquiry into the discrimination he faced, I’m sure there will be many witnesses who will say this,” Padavala says. This was independently confirmed by colleagues of Nagaraju’s in The New Indian Express who requested anonymity.

Resident Editor of The New Indian Express in Hyderabad G S Vasu denied these allegations. “The questions are based on hearsay or information given by unidentified persons, while the facts are otherwise. I am referring your mail to our corporate HR/Legal dept for an appropriate response,” he said in an email. The News Minute has received no response since. The NIE staff across bureaus have been asked by the paper's Executive Editor to voluntarily contribute to support the family of Nagaraju.

A protest outside The Indian Express office in Hyderabad.

Whether or not Nagaraju was discriminated against, may only be revealed by an impartial inquiry conducted by an independent team, or as his friends demand, an investigation by the police invoking the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (Prevention of Atrocity) Act 1989. For the few Dalits who break into the ivory tower that is the English media, these allegations echo their own experiences.

Ravi Kumar, an alumnus of the Asian College of Journalism (ACJ) and also a Madiga, had applied for a position in Hyderabad at The New Indian Express. ACJ is one of the few private educational institutions which offer scholarships to SC and ST students.

Ravi says that when he went for the interview in Chennai, he was asked about his social background since his resume indicated that he studied on a scholarship. He told his interviewers that his parents were daily wage labourers. He was then offered a monthly salary of Rs 14,500, which was much lesser than most of the other candidates who were selected for the same position.

“When I asked them why, they told me it was because I studied in Telugu medium and that my writing skills were not good enough. If that was the case, I would not have cleared the exam (conducted by the newspaper) and they too said that my results were good,” Ravi says, adding that there were one or two others who had been offered the same financial package, but he does not know if they were Dalits. “I felt that I got a lower salary because of my caste,” he says. Eventually, he decided to pursue higher studies.

In his 10-year research on Indian language newspapers, academician Robin Jeffrey found that the standard response he got when he asked editors why the number of Dalit journalists in the media is disproportionately low was the same given to Ravi Kumar: lack of qualifications.

“Qualifications” is euphemism for knowledge of English. Fresh editorial recruits in most media houses today are at least graduates, although this may not hold true for stringers.

However, sub-editors in all print news media organizations concur that even their ‘qualified’ recruits file the most sub-standard copies, devoid of grammar and sometimes bordering on gibberish. Some sub-editors even have secret files of raw copies which they can laugh over on a bad day.

Two examples: “RDPR Minister Jagadish Shettar on Wednesday informed the Legislative Assembly that Rs 49.20 crore had been released to augment shortage of drinking water.”

“The incident came to light when the morning joggers noticed the lifeless corpse, who then immediately informed the police.”

(For more examples, see the PDF document at the bottom or click here)

If, as editors routinely claim, merit is the only criteria that matters when hiring a journalist, how is it that such poor copies are filed routinely?

Anybody who’s been a journalist long enough will tell you how important networks are in the profession, as they are elsewhere.

Journalism often runs in families, usually of course, being passed on from father to son, rarely to daughter. At one national English daily, the post of a district reporter in Tirupati has been passed down from father (an upper caste man) to son, and then grandson. The same newspaper also has four members of the same family working in Karnataka. There is a network ready and waiting for many people who belong to the upper castes, and hence they tend to dominate even in newsrooms. Just as men of all castes have some advantages over women of all castes, so too, do upper castes have certain advantages over people of other castes.

For the odd Dalit journalist who makes it to such a newsroom, the workplace becomes a source of anxiety that is unrelated to his (Dalit women are even fewer in number) competence as a journalist.

D Karthikeyan, formerly with The Hindu’s Madurai bureau says that casteism operates in very subtle ways in the newsroom. He had always been open about his Dalit identity and that made the workplace a daily battle zone for him.

“Everybody, from my colleagues to the office staff, knew I was a Dalit. Caste discrimination operates in multiple subtle ways. For instance, irrespective of whether a good story of mine was caste-related or not, none of my colleagues, except my chief of bureau who was a good man, ever congratulated me. They don’t recognize you,” he says.

Innuendo was a part of the work culture. “They never say anything directly. But if a Dalit politician like Mayawati or A Raja was involved in corruption, they would say that Dalits use their position for corruption. They would loudly say this in my presence,” says Karthikeyan.

At one point, Karthikeyan approached the then editor-in-chief N Ram about it, who then intervened.

A young journalist with an English newspaper who requested anonymity says that he too faces snide remarks as he covers human rights and caste issues. “Often, they tell me things like ‘Oh, you cover only such issues’,” says the reporter, the only Dalit in the newspaper in south India. “These issues are covered by the others only if it is assigned to them, or if I am not working that day. None of them ever get bylines for caste-related or human rights stories,” he says.

A few years ago, a journalist had initiated a consultation among fellow journalists to initiate an archive of the work done by Dalit journalists. While it was welcomed by many, Dalit reporters objected because not revealing their Dalit identity afforded them an anonymity with which they could freely pursue stories of all kinds without being burdened by the “Dalit” tag.

Many senior journalists – Kalpana Sharma, Sevanti Ninan, Siddharth Varadarajan, Ammu Joseph, Paranjoy Guha Thakurtha and others – have underscored the necessity of newsroom diversity and the need to include marginalized groups and minorities among editorial staff in the media.

However, Karthikeyan says even when the inclusion of Dalit journalists is spoken about, the mental image is that of a man; Dalit women are still not part of the landscape.

But while the entry of women in general in the media has been celebrated, questions raised about the inclusion of Dalits bring accusations of “casteism”. “In India, if you raise women’s issues you are feminist, but if you raise Dalit issues you become casteist. It’s like saying Nelson Mandela was racist,” says journalist Sudipto Mondal, who is with an English newspaper.

In his book India’s Newspaper Revolution, Robin Jeffrey compares the situation of Dalits in Indian journalism with that of the African Americans in the United States of America. But Dalits do not have the backing of a commercially successful trading community or a socially influential church, which the black community had to start their own newspapers.

With the slogan “We wish to plead our own cause. Too long have others spoken for us.” On the front page, Samuel E Cornish and John B Russwurm founded the first black newspaper Freedom’s Journal, 30 years before the 1857 Mutiny in India.

On finding almost no black journalists in the American press in the 1970s, the American Society of Newspaper Editors (ASNE) set itself a time-bound goal of ensuring that newspapers hired black journalists in proportion to their general population. It is a different matter that they never achieved their goal, even though there has been improvement.

Urging that the Indian media follow the example set by the ASNE, a delegation of Dalit intellectuals approached the Editors’ Guild and Press Council of India in 1996. Chandra Bhan Prasad and Sheoraj Singh Bechain had submitted a memorandum titled “End Apartheid from Indian Media: Democratise Nations Opinion”. The PCI had said that it was beyond the scope of its powers to intervene in the private companies. However, Shivnarayan Rajpurohit, who was a part of the delegation, argues that the PCI does have enough powers to make the media more socially inclusive.

According to Prasad, the memorandum was also submitted to every newspaper in Delhi. Calling the Indian media an "upper caste republic", Prasad said: “We never received an acknowledgement of the memorandum from the Editors’ Guild or the newspapers. The only exception was Chandan Mitra of The Pioneer, who gave me a column called Dalit Dairy which I wrote for 15 years. I missed only three Sundays."

By 1996, India had been independent for close to half a century, but never in that time it appears, had it occurred to anybody that Dalits (by default male) were simply missing from the journalistic fraternity. What prompted Uniyal to begin his search for a Dalit journalist was a question from the Delhi-based correspondent of The Washington Post Kenneth Cooper. “And worse still was the thought that… it had never occurred to me that there was something so seriously amiss in the profession,” Uniyal is quoted as saying in Jeffrey’s book.

Karthikeyan says that democracy did not just mean that one has the right to vote, adding that it was necessary that the democratic ethos spread to public institutions as well. “What sort of democracy is this, if such a huge population is left out of the media in the most hierarchical society in the world?” Karthikeyan says.

The debate about the inclusion of Dalits and other marginalized groups – including women of these groups – is part of the larger debate about the inclusion of these groups in other spheres of life. Over a hundred years ago Jyotirao Phule argued that the lower castes and women were both oppressed by Brahminical patriarchy.

But while a feminism that talks about 50 percent reservation in Parliament has found wide acceptance, calls to make the public sphere caste-inclusive have not.

Asked if he knew a Dalit woman journalist I could speak to, Karthikeyan said he didn’t. Perhaps it is now time to write “In search of a Dalit woman journalist”, as Uniyal titled his piece for the Pioneer when he wrote of his search for a Dalit journalist in 1996.

P.S. Meanwhile, Nagaraju’s friends and the DUJ have protested against The New Indian Express in front of its office in Delhi. The voices for “justice for Nagaraju” are growing louder.