On Sunday evening, as dusk fell, Shaila* walked in the paddy fields owned by her family along with her cousin. They were going to light the “thudar” a lamp (more accurately torch), fashioned out of a tree stem that is several feet tall. Propped up to one side of the paddy field, the thudar would be decorated with the kepula flowers that grow in the surrounding hills.

“It was just my cousin and me this year,” 55-year-old Shaila told The News Minute. Standing before the torch, she called out in Tulu: “Bali, come to the kingdom that you ruled”. She said this thrice and each time she and her cousin would throw grains of rice at the lamp, followed by cries of “kooo”.

“That’s all we did because no one else is at home this year,” Shaila said. Last year, her daughter and son-in-law were present for the celebration.

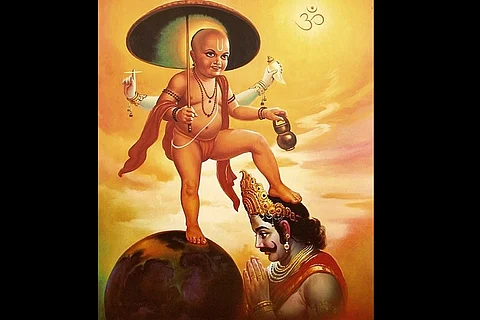

In the paddy fields of Tulunadu – Udupi and Dakshina Kannada districts of present day coastal Karnataka – similar scenes would have played out. Traditional torches are lit up by the farmers for Deepavali for Bali Chakravarthi, the benevolent king who was banished to the underworld by Vamana, an avatar of Vishnu. He is also called Baliyendra.

“Bali Chakravarti is our benevolent Dravidian king. For three days, we invite him. We dress well, eat well, so that he can see that we are prospering,” explains 58-year-old Sheenappa, Shaila’s husband. The couple live in Mukka, a coastal town in Dakshina Kannada district.

After calling out to Bali, the custom is go to the cattle sheds and ask them to see the lamps that are placed there. “Back then, wealth was of two types. Crops and cattle,” Sheenappa says.

Many of the communities of coastal Karnataka have a unique socio-religious culture. Although there are various hierarchies within these communities, their world view is different. For instance, religious belief is centred around the bhoota-worship (spirit worship) the emotional underpinning of which, is “bhaya-bhakti” (fear and devotion, not just devotion). Brahmin priests have no role to play here, although the Brahmin residents of the village do participate.

According to Abhay Kumar, lecturer at the SVPB Adhyayana Samsthe at Mangalore University, the celebration used to be an elaborate village affair until about 40 years ago, before the land ceiling laws ended the zamindari system.

He explains that various communities in the region (except Brahmins) that are associated with paddy cultivation celebrate Bali’s return. In the past, the ritual would be organized through the gutthu mane, and those who had ties with that gutthu mane would participate in the celebration.

(Gutthu mane is loosely translated as the big house. Gutthu mane could belong to a Bunt, Billava, Gowda or Jain family. Families which have the gutthu mane traditionally organize social and religious festivals, and exercise influence in the village. They were also often large land owners, although land reforms have brought about many changes.)

A tree about 20-feet tall would be cut and brought from a forest and erected in a corner of the field in a ceremony simply called the planting of a tree. A type of seven-point crown would be made of twigs by a person belonging to the Vishwakarma caste, and it would be fixed atop the main tree by a person of the Billava caste. This person would also light the seven tips of the crown, as lamps, Abhay explains.

On either side of this, two torches called koltiri made of the Belakki tree (about 6 feet tall) would be erected and lit. A mixture of some food items – called agelu – is placed at the bottom of this structure.

After sundown, all the people associated with the gutthu mane gather for the ceremony. Before the head of the gutthu mane calls out to Bali, there is a short burst of music – the conch shell, a type of brass plate and a drum.

The ritual practiced today are diluted variations of this, and differ in scale depending on each family.

In Kundapura, most agricultural families have a meke-kamba (a type of pillar) to which a three-pronged torch is tied and lit up to invite Bali, says Jayaprakash Shetty, a lecturer at the Government First Grade College in Thenkanidiyur, Udupi district.

Jayaprakash says that the three-pronged torch and the meke-kamba resemble the linga, a Shaiva symbol. He says that the story of Bali being pushed down to Patala by Vamana is a manifestation of the battle for power between the Vaishnava (Vishnu) and Shaiva (Shiva) traditions of worship. “You have to look out for Vamana’s steps (stamping out Shaiva traditions) everywhere,” Jayaprakash says.

“Delhi’s (cultural) history does not belong to us. In our folklore, even Goa and Maharashtra are foreign lands,” Sheenappa says laughing.

However, Sheenappa says that these communities have lost out on much of their culture. “These are so-called primitive rituals. So, this sense of insecurity has been there. Now, we are neither here nor there. Our culture is unique, but we’ve changed and become copy cats. They (north Indian people) haven’t deviated from their culture,” Sheenappa says.

(Names have been changed on request)