Lakshmi, who migrated to Bengaluru from Kadapa in Andhra Pradesh runs a Paying Guest (PG) hostel in the city that is now running at just 10% occupancy since the COVID-19 lockdown. She migrated with her mother in 2014 after mortgaging her father’s farmland to a local moneylender, and invested the money into renting, furnishing and managing a PG in the Mahadevapura area. Today, she is left in a debt trap as most tenants have vacated the PG after the lockdown began in March.

PG operators such as Lakshmi are invisible stakeholders in this housing segment. Here, operators take a property on lease for three to five years from landowners, and run it as their primary livelihood. As part of an ongoing study on the PG hostel sector by the Indian Institute for Human Settlements (IIHS) in Bengaluru, we found that 15 PG operators we spoke to came from a less privileged socio-economic background than their landlords and even a majority of their tenants.

As part of a quasi-formal sector, operators are neither tenants nor landlords and remain unrecognised by both the central and state governments. Consequently, they have been left out of the conversations and advisories initiated after the COVID-19 lockdown to support either tenants or landlords.

Eight PG operators who were interviewed reported financial and psychological distress, caused by the coronavirus, with occupancy rates falling from the usual average of 80% to just 10% after the lockdown. They expect business to be shut for at least nine months – until December 2020.

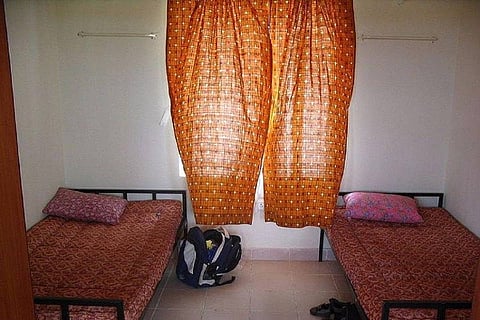

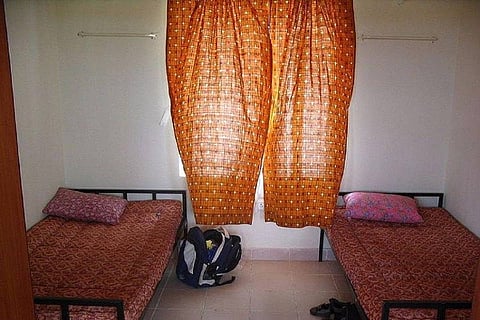

These PGs typically accommodate between 80 and 200 people, with rooms shared by two to six people, and common amenities like WiFi, a TV and a washing machine. The monthly rent tends to be between Rs 4,000 and Rs 8,000, inclusive of meals and housekeeping. Considering their affordability and viability, PGs are a popular option among students and young professionals in Bengaluru.

Over 60% of Bengaluru’s urban population consists of in-migrants, and nearly 20% of in-migrants are in the age group of 15 to 34, with education or employment as the primary reason for migration, according to the 2011 Census.

Though the PG segment in Bengaluru meets the housing needs of a sizable portion of young migrants into the city, it does not figure in official data such as the Census or in the National Sample Survey (NSSO).

The Mahadevapura Zone alone, which accounts for around 22% of the BBMP area, has as many as 1,400 PG hostels. This is one of the zones with high demand, owing to its connectivity as an entry point from the states of Tamil Nadu and Andhra Pradesh, and the employment opportunities in close proximity in the IT/ITes hubs such as Whitefield and International Tech Park (ITPL).

Many young migrants who come to work in this area prefer PGs over the typical housing market for two main reasons -- they needn’t pay Bengaluru’s high 10-month security deposit, and they needn’t invest in utilities and furnishing, both of which are handled by operators.

The growing demand for PGs has influenced the real estate market to adapt and leverage profits from this. Real estate brokers often use this opportunity to attract entrepreneurial enthusiasts with minimal experience and awareness about real estate to invest in PG hostels, by drawing their attention to the high occupancy rates and the promise of good returns on their investment.

Naidu, a former food caterer in Hyderabad is one such operator who was attracted by this business idea despite no prior experience in it. “My food catering business was hampered due to state bifurcation in 2014, and I moved to Bengaluru and established an Andhra style home food catering business. After a couple of years, I realised that there is a huge demand for PGs, and started this business. I was operating three PGs, one of which I have already closed. Now I am planning to close the other two as everything is in debt now,” he says.

Before the national lockdown was imposed on March 23, 2020, the Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA) sent out an advisory to all educational institutions and office spaces to shut down for safety reasons, and asked everyone not to step out of their homes. During this period, a majority of in-migrants including those living in PGs temporarily moved to their hometowns, assuming that they would return to Bengaluru soon after the lockdown.

But the continuous extensions of the lockdown, coupled with the fact that the pandemic is seeing no clear end has led to them not returning thus far.

In March 2020, the BBMP issued an advisory supporting tenants by asking landowners to waive or defer rents, and the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) also issued a circular in the same month to banks and financial corporations (Non-Banking Financial Institutions) for a moratorium on formal loans. While landowners or people operating in more formal sectors may be able to use the moratorium, businesses such as these are based on informal loans.

PG operators, not being recognised in these advisories, report that they have been made to waive rent from tenants, but have but have to continue paying landlords and maintaining the premises. “We have been given no relaxation. The landlord hasn't reduced the rent or given us extra time to pay the rent, and has also threatened to not renew the rent agreement if we don't pay the full rent. The rent has also increased annually by 7.5% and he is doing that this year despite the lockdown,” says Reddy*, a PG operator in Marathahalli.

The operators interviewed also reported that they aren’t eligible for the loan moratorium as they arranged this money either using informal moneylenders or from their family. “I borrowed money from my family members, and my husband borrowed money from his friends. Now we cannot see any future in this business, and don’t know how to face our family and friends,” says Venkat, who came to the city from a village near Anantapur, Andhra Pradesh.

These operators represent a section of people who have migrated from rural areas and are now trying to move up the ladder from a less organised business to a more formal, quasi-professional sector. This sector is also evidently important to a proportion of young in-migrants who depend on them for affordable housing.

The COVID-19 lockdown has reiterated the need for such sectors to be better recognised and supported from public institutions, which can benefit tenants while also allowing the operators to move up the socio-economic ladder.

*Names have been changed on request

Sairama Raju Marella is an architect and urban planner who works at the Indian Institute for Human Settlements (IIHS). His research is around rental housing, tenancy laws, policies and programmes in India.