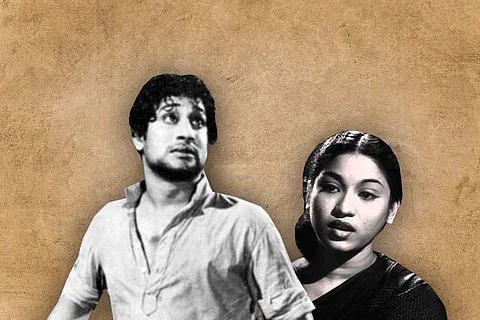

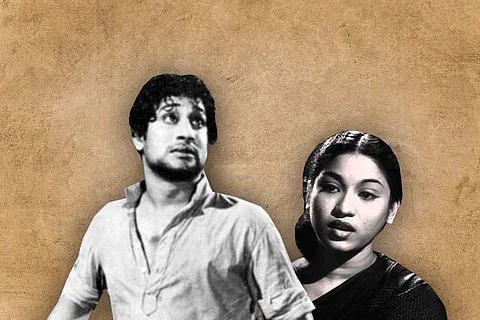

The year is 1952. Tamil Nadu is set to welcome on theatre screen, a debutant actor who will go on to become one of the most recognisable faces of Kollywood. The film’s script is written by another figure who will shape the state’s political future. The actor was Sivaji Ganesan, then unknown to Tamil audiences, and the scriptwriter was M Karunanidhi, who in celebration of his oratorical skills and scholarship, would later be called ‘Kalaignar’.

Parasakthi was released 70 years ago on October 17, 1952, stunning audiences with powerful dialogues on the abuses of religion and state apathy. The film continues to occupy cult-status in Kollywood. Of course not even that has spared it from being satirised on screen or becoming material for memes. But perhaps it’s a light-hearted take on Parasakthi's commentary about the sacredness of things? Regardless, the movie’s message—particularly the unforgettable courtroom sequence when Sivaji delivers his famed monologue—has endured for seventy years since its release. In his paper, ‘Parasakthi: The Life and Times of a DMK Film’, MSS Pandian says the popularity of the film’s dialogues was so great that street-theatre artists would give extended performances based on them at Madras city’s Moore Market.

Parasakthi, set in 1942, tells the tale of Gunasekaran (Sivaji Ganesan), who is forced to migrate to Myanmar’s Yangon (then Rangoon) for employment and his sister Kalyani (Sri Ranjani). The story is long-winding, peppered with jabs at Brahmanical ideologies and Congress leaders like Rajagopalachari amongst others, second-class treatment of Tamils by Delhi’s elite and superstition. Its messages are still crystal clear.

Kalyani goes through a turmoil of her own. After her husband and her father’s death, she is bankrupt while having to care for their toddler. Kalyani only finds abuse and assault at every turn as she flees from place to place unsuccessfully trying to establish a dignified life for herself and her child. Gunasekaran upon his return to Tamil Nadu sets out on an arduous task—to trace his sister. In the final place she takes refuge in, a Parasakthi (mother goddess) temple, the priest attempts to rape her. Kalyani escapes but feeling defeated, tries to die by suicide after taking the life of the child. Only to be stopped and arrested for attempted suicide and murder.

And this brings us to a courtroom scene that isn’t talked about nearly as often as the one later in the film with Sivaji’s monologue. It is no less powerful, though. Kalyani when produced in court is defiant. “Aren’t you a murderer?”, the judge askes her. “According to your law, yes. Not according to any justice,” she retorts. The judge, taken aback, asks what kind of justice it was to kill her own child. An unfazed Kalyani needles him with the reply, “With the same right I gave birth to the child, I destroyed her myself.”

The dialogues don’t defend the idea that parents can take the life of their own children. It was instead intended to shock. The judge, now furious, tells her that everything that was created belongs to the government. Karunanidhi’s plays with the language here. In Tamil, the judge says “sontham” to mean ‘belong’, but it can also mean relatives. “Sontham?” Kalyani repeats, grinding the word between her teeth. “We starved. We roamed everywhere in search of some comfort. But we were treated worse than diseased dogs are. We become no more than scrabbling worms in our hunger. Did the government come to the aid or comfort of its ‘sontham’ then?” What ties did the government have with her or the child to evoke this right now, Kalyani asks.

Setting aside the fact the common cinematic practice of letting an accused and judge engage in arguments isn’t the way real-life court proceedings work, the sequence is a damning statement on how law and justice too often don’t mean the same thing. Kalyani continues to lambast laws and rules that are apathetic to the living but criminalises the desperate acts of people cornered by the cruelty of powerful men.

At this point, Karunanidhi’s dialogues for Kalyani, in DMK’s cinema tradition, refer to the literature of the land. She tells the judge that she was seeking death for herself and her daughter in the hope of finally finding peace. “If what I did was a crime, then was Nalla Thangal, who killed all seven of her children, a criminal too?” The sordid story of Nalla Thangal is hundreds of years old. Its exact origin is unknown though several states in the south including Tamil Nadu have versions of her tale. Nalla Thangal, similarly driven to desperation due to poverty and isolation, throws her children into a well before taking her own life. In Parasakthi, Kalyani chooses a river. The abject bleakness of both women’s stories and the seemingly steadfast notions of right and wrong that crumbles because of their actions are what has given them their lasting endurance.

Interestingly, the Nalla Thangal story found its way back into courts even after Parasakthi. This time, the real-life ones. At least thrice, as recently as this year in July, Tamil Nadu courts have evoked what has been dubbed the ‘Nalla Thangal Syndrome’ to lighten the judgement on poor women accused of killing their children due to extreme poverty.

Again, the stories, neither Kalyani’s nor Nalla Thangal’s, are to be interpreted as a rationale for murder. They, instead, challenge the easy morality of the privileged. Hopefully, they can serve as a call for empathy. Perhaps they direct our collective anger at systems that produce Kalyanis and Nalla Thangals everywhere, not just in Tamil Nadu.