Scientists applying Google artificial intelligence data from NASAs Kepler Space Telescope have discovered an eighth planet around the star Kepler-90 -- breaking the record for the star with the most exoplanets and, for the first time, tying with our own.

The planet Kepler-90i, described at a briefing on Thursday and in a paper accepted for publication in the Astronomical Journal, demonstrates for the first time that other stars can host planetary systems as populous as our own solar system, the Los Angeles Times reported.

The findings also establish the growing role that neural networks and other machine learning techniques could play in the hunt for more elusive planets outside our own solar neighbourhood.

"Kepler has already shown us that most stars have planets," said Paul Hertz, director of NASA's Astrophysics Division in Washington. "Today, Kepler confirms that stars can have large families of planets just like our solar system."

Kepler-90i sits around a sun-like star, which is 2,545 light years away in the constellation Draco.

NASA/Wendy Stenzel

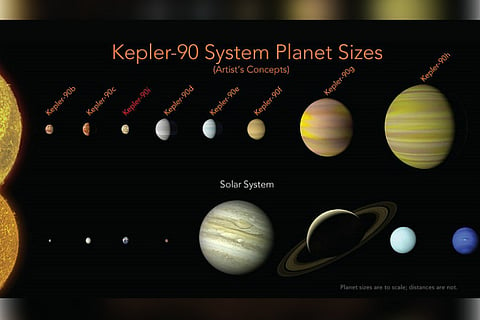

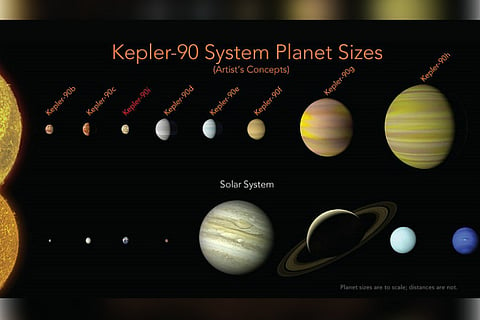

Like the Earth, Kepler-90i is also the third rock from its sun - though it sits much closer, circling its star every 14.4 days. The two small planets within its orbit (planets 90b and 90c) revolve around Kepler-90 every seven and nine days, respectively.

The next three planets beyond Kepler-90i's orbit (90d, 90e and 90f) fall into a sub-Neptune size class and orbit every 60, 92 and 125 days, respectively. The last two planets, 90g and 90h, are Jupiter-class gas giants, and take 211 and 332 days, respectively, to make a round trip.

All of the planets except for 90i were previously known. That put the Kepler-90 system in a tie with the seven-planet Trappist-1 system for the honour of most populous known exoplanet solar system.

In some ways, the Kepler-90 system seems to echo our own, with small rocky planets (Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars) closer in to the sun and larger, more gas-rich ones (Jupiter and Saturn, Neptune and Uranus) lying farther out.

Scientists think there is a reason the larger planets orbit farther from their sun: It's the cool place to be.

NASA/Ames Research Center/Wendy Stenzel

"In our own solar system, this pattern is often seen as evidence that the outer planets formed in a cooler part of the solar system, where ice can stay solid and clumped together to make bigger and bigger planets," said Andrew Vanderburg, an astronomer at the University of Texas at Austin and one of the authors of the forthcoming study.

The same phenomenon could be at work here, scientists said.

But the exoplanet system differs from ours in at least one major way: All eight planets' orbits would lie well within that of the Earth, which takes 365 days to circle our own sun.

The researchers said they aren't sure why the Kepler-90 system has such a crowded field. It could mean that at least some of the planets formed farther out and were eventually drawn inward.

NASA/Ames Research Center/Wendy Stenzel

Regardless, it means that Kepler 90i, third rock though it may be, is too hot to be habitable.

"Kepler-90i is not a place I'd like to go visit," Vanderburg said, adding that the planet probably has an average temperature of about 800 degrees Fahrenheit (426 degrees Celsius).

How the planets were discovered

The Google AI found exoplanets using data from NASA's Kepler Space Telescope.

In this case, computers learned to identify planets by finding in Kepler data instances where the telescope recorded signals from planets beyond our solar system, known as exoplanets.

The discovery came after researchers Christopher Shallue and Andrew Vanderburg trained a computer to learn how to identify exoplanets in the light readings recorded by Kepler -- the minuscule change in brightness captured when a planet passed in front of, or transited, a star.

Inspired by the way neurons connect in the human brain, this artificial "neural network" sifted through Kepler data and found weak transit signals from a previously-missed eighth planet orbiting Kepler-90, in the constellation Draco.

While machine learning has previously been used in searches of the Kepler database, this research demonstrates that neural networks are a promising tool in finding some of the weakest signals of distant worlds.

Shallue, a senior software engineer with Google AI research team, came up with the idea to apply a neural network to Kepler data.

"In my spare time, I started googling for 'finding exoplanets with large data sets' and found out about the Kepler mission and the huge data set available," said Shallue.

First, the researchers trained the neural network to identify transiting exoplanets using a set of 15,000 previously-vetted signals from the Kepler exoplanet catalogue.

In the test set, the neural network correctly identified true planets and false positives 96 per cent of the time.

Then, with the neural network having "learned" to detect the pattern of a transiting exoplanet, the researchers directed their model to search for weaker signals in 670 star systems that already had multiple known planets.

Their assumption was that multiple-planet systems would be the best places to look for more exoplanets.

"We got lots of false positives of planets, but also potentially more real planets," said Vanderburg.

"It's like sifting through rocks to find jewels. If you have a finer sieve then you will catch more rocks but you might catch more jewels, as well."

Kepler-90i wasn't the only jewel this neural network sifted out. In the Kepler-80 system, they also found a sixth planet.

This one, the Earth-sized Kepler-80g, and four of its neighbouring planets form what is called a resonant chain - where planets are locked by their mutual gravity in a rhythmic orbital dance.

The result is an extremely stable system, similar to the seven planets in the TRAPPIST-1 system.