On May 19, the Supreme Court of India observed that sex work is a profession, and that sex workers should be given the same rights and dignity as people engaged in any other profession. A bench of Justices L Nageswara Rao, BR Gavai and AS Bopanna said that all individuals are entitled to protections under the law, including sex workers, and told the police not to abuse or harass them, and to provide all necessary facilities available to any other citizen to sex workers who file sexual assault complaints. While these are observations of the court and don’t amount to either decriminalising or legalising sex work in India, activists say that the observations embody the essence of decriminalisation, which has been a long-standing demand of sex workers in the country.

The dominant narrative around sex work tends to revolve around pity, exploitation, and condescension or disgust over the nature of sex work. Another assumption is that everyone in the sex trade is either trafficked or there out of coercion. While exploitation and harassment of sex workers are important issues that need to be addressed, and trafficking of all forms must be dealt with strongly, many times, the discourse around the issue fails to take into account the voices and lived experiences of sex workers. In fact, decriminalising sex work is the first step to ensuring that they’re are not exploited or harassed, say sex workers.

Saradha (name changed), a sex worker based in rural Ernakulam in Kerala, says that she has been exploited many times, where her customers have refused to pay money for her services. “Though people consider me a ‘bad woman’, many come to me for sex. They know of the work that I do — they abuse me, assault me…Some also demand sex, and just leave without paying afterwards,” she says. “I’ve always wished that I could go to the police and file a sexual assault complaint,” Saradha adds, but she cannot, because sex work is seen as illegal in the country — even though it technically is not.

Sex workers are often booked by the police under the Immoral Traffic (Prevention) Act, along with sections of the Indian Penal Code, and the Juvenile Justice Act. Beyond this, the Indian law is vague on sex work; it is not illegal, but is regarded as an “immoral” profession. So, while an individual can practice sex work, they can also be incriminated for soliciting, doing it publicly, or owning a brothel. Add morality politics and stigma, the present system not only makes sex workers vulnerable to police atrocity and violence, but hinders their access to social welfare schemes and healthcare.

Living Smile Vidya, a theatre practitioner and the author of I am Vidya: A Transgender’s Journey, points out that while sex work is looked down upon, the trade has been around for a long time. “It exists because most adults do want to have sex, but may not always seek it in the traditional ways of a relationship. If the law recognises that it is something normal, it can be a vocation, the services for which can be purchased without attaching morality to it, it helps sex work become normalised,” she says.

Decriminalisation of sex work is not the same as legalisation. While the latter would mean bringing sex work under regulation such as where, when, and how it should be practiced; decriminalisation would give more agency to sex workers by eliminating discrimination and laws being used against them for being sex workers.

Nalini Jameela, a writer and activist for sex workers, stresses on decriminalising sex work and regularising brothels. The author of Autobiography of a sex worker — a fiery critique of society’s fake morality — says, “Sex work shouldn't be legalised, because that would create scope for licensing, which has many loopholes for corruption. But decriminalising it will help against arrests, and the stigma against sex work. We can then question those.”

A transgender sex worker from Kozhikode, Latika (name changed) says the hardest part of her job is dealing with the police. “It is very painful how the police behave with us. Earlier, there was assault; now there is just verbal abuse,” she says. “People come in huge cars, make use of us and just run away without paying sometimes. Some hit us for their pleasure, but we cannot complain. So, if some legal support is there, survival would become easier. Apart from all this, I like doing this job. I consider it work. Where else will someone accept us?” she asks.

For many transgender persons ostracised by their families and denied other livelihoods, sex work is one of the two main sources of livelihood — the second being begging.

Rachana Mudraboyina, a trans rights activist, points out that legitmising sex work as a profession by decriminalising it will allow for unionisation of sex workers, which has been proven to improve health indicators and wellbeing; it will also help prevent trafficking, she says.

Rachana gives the example of Sonagachi, the red light area in Kolkata, and how collectivisation of sex workers led to these benefits. The Durbar Women’s Collaborative Committee (DMSC) was a result of the Sonagachi HIV/AIDS Intervention Project, and included men, women and transgender sex workers.

The Sonagachi Project aimed to empower and protect sex workers through community initiatives like rallies, creating spaces for social participation, and reducing the risks of HIV. As a result of DMSC’s efforts and protests, they were able to tackle police discrimination in the community. Studies also show that it led to lower HIV rates among sex workers.

Presently, while there are sex workers unions in the country, many of them face challenges in getting registered and being recognised due to the ambiguity in the Indian law to recognise sex work as work.

Nisha Gulur, the vice president of the National Network of Sex Workers, has also been associated with the sex workers’ union in Karnataka. “We have been fighting with the state government for registration of the union for a decade. However, the department says that if we need to register, we need to have an employer. Due to the unorganised and exploitative nature of the industry, we are facing these issues,” Nisha tells TNM.

She adds that as a union, sex workers could ask for labour rights: “In Karnataka, we are not asking for 100% zoning (a single red-light area), but for some zones for sex workers where we are given a good work environment, hygienic food, water and lodging, a nursery for children. To demand these, we need sex work to be decriminalised and recognised as work.”

Unionisation can also prevent trafficking because the community becomes responsible for itself, and its rights. Rachana explains, “If the sex workers in a red-light area can form a committee and have more autonomy, they will know when a minor has been trafficked into the area. Instead of being at the mercy of exploitative brothel owners, traffickers and pimps, they can intervene right there and help rescue the trafficked woman or girl right then, instead of years later.”

In places like Kerala, where sex workers are not very well organised, this lack of a safe place to work poses further challenges. The Supreme Court said in its May 19 order that while running a brothel is unlawful, voluntary sex workers should not be harassed during a raid if they are found there. Nalini counters this though – she says that brothels could be allowed to run if they provide voluntary sex workers a safe place to practice their vocation and meet clients.

“In Kerala, sex workers spend a lot of money to commute to areas where they can find clients. Brothels should be allowed as it helps to find clients easily, but the problem now is that a majority of a sex worker’s earnings go to the brothel owner, which needs to change. Brothels can give space to unify the sex workers so they can demand these rights once sex work is decriminalised,” she says.

Additionally, it could pave the path for social welfare schemes for sex workers. “Many sex workers become brokers (pimps) once they reach 35-40 years of age. However, if they have some social welfare schemes, and decriminalisation reduces the stigma, they may not need to turn to brokering. It could open up other avenues of work for them, reduce trafficking, and so on,” Nisha says.

“Sex workers’ rights are human rights,” asserts Grace Banu, the founder of Trans Rights Now collective, “and people doing it voluntarily should be respected.”

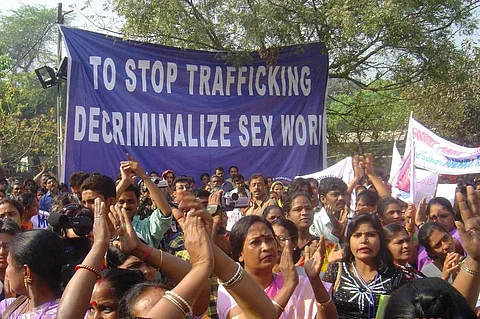

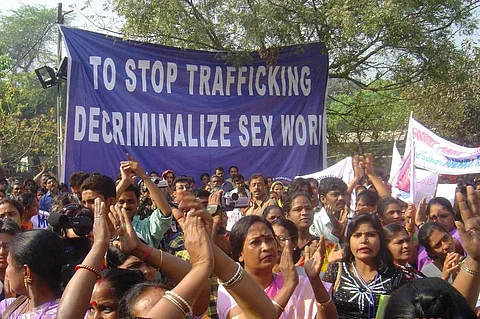

India does not have a law decriminalising or protecting sex workers explicitly. However, in 2018, sex workers protested against the Trafficking of Persons (Prevention, Protection and Rehabilitation) Bill (now an Act, ITPA), which aimed to protect women from sexual exploitation. Those in the trade argued at the time that the law allows for conflation of consensual sex work with trafficking — thereby assuming that every sex worker is either a victim or trafficked. Concerns ranged from fear of increased police harassment to raids – which remain till date.

The Supreme Court also took cognizance of another aspect of the above assumptions, and said, “No child of a sex worker should be separated from the mother merely on the ground that she is in the sex trade. Further, if a minor is found living in a brothel or with sex workers, it should not be presumed that he/she has been trafficked. In case the sex worker claims that he/she is her son/daughter, tests can be done to determine if the claim is correct and if so, the minor should not be forcibly separated.”

“No one is denying that trafficking happens in sex trade,” says Rachana. “But the fact also is that police often want to show numbers about how many arrests they have made, how many complaints registered. We know that arbitrary rescue and rehabilitation does not empower victims.”

There is documented evidence to show that many who have been ‘rescued’ from sex work and placed in shelter homes often find their freedoms curtailed, and many return to sex work. In their 2018 EPW article, In Its Haste to Rescue Sex Workers, 'Anti-Trafficking' Is Increasing Their Vulnerability, Aarthi Pai, Meena Saraswathi Seshu, and Laxmi Murthy talk about the problems with seeing trafficking more as a “moral” problem than a crime, which translates to an "anti-sex worker approach" on ground. The authors’ two-phase study, which involved a total of 417 sex workers from four states, detailed how forcibly rescuing women in sex trade compelled them to face humiliating situations with their families who were unaware of their vocation, and resulted in debt bondage due to having to pay for legal fees, bribes and bails. Many were found to have entered sex work due to their financial situation; and they wanted to continue in the profession. Only 0.82% of the 243 sex workers interviewed in phase two of the study were found to be minors, as many as 79% said they were in sex work voluntarily. Fifty five percent of the rescued women who had been trafficked, returned to sex work after their release from correction homes.

Calling rescue and restore raids “indiscriminate, violent, and destructive of sex worker communities,” the authors state, “Generations of police raids have not been able to combat the menace of trafficking in persons. The only light at the end of this dark tunnel comes from the collectives of vigilant sex workers who are organising themselves to root out the violence and abuse in their own lives and that of minors and women trafficked into sex work.”

“Most people who come into sex work do so because of their circumstances,” acknowledges Nisha. “However, if one has entered the industry due to whatever reason 5-10 years back, how will it help if the government rehabilitates them now? Now that she is earning money and feeding her family, forcefully removing her from her place of work, compelling her to learn more “respectable” jobs like tailoring which may not pay as well, is counter-productive. If the entry into sex work has to be dignified, then so does the exit,” she states.

For Living Smile Vidya, sex work is not something she would choose. However, if someone says they are doing it voluntarily, she says she would not disrespect or judge them. “How people enter into sex work is always complicated. Some trans persons make the trade-off or don’t mind doing sex work if it helps them earn the money they need for [gender affirmation] surgery,” she says.

In a conversation with Sanhati in 2013, Smiley explained that certain sections of people – like transgender persons – practice a certain profession more than others because they aren’t given other options. “This occupational fixity in both Dalit and transgender communities, is done by closing off alternative options. Thus, manual scavenging becomes an occupation enforced on Dalits through the exclusion of access to other jobs; in a similar way begging and sex work are forced occupations for transgender persons through exclusion from other jobs,” she says, adding, “So, by repetition historically and by not providing alternative options, these jobs become fixed.”

There is merit to considering these factors when we talk about sex work and decriminalisation. Women from many marginalised communities are forced into sex work, and systems like Devadasi and Jogini also legitimise sexual exploitation of marginalised women as part of certain religious practices. Given that these women may neither have access to resources to articulate exploitation, nor the freedom to safely speak up out of fear of violence from dominant communities, it is a pertinent question whether decriminalisation of sex work could be used to continue appropriating these women’s voices to say their sexual exploitation is voluntary sex work.

“In some states, Dalit women are forced into sex work. Then, a Dalit woman or trans person will not have a safe space to say she is being forced. Also, how will the most marginalised sex workers know what the Supreme Court has said and use it for their protection?” Grace questions. “Perhaps, along with decriminalisation, the government could consider giving ID cards to those doing sex work, and a vetting process to ensure it is voluntary. Some countries have it. They could look at setting up mechanisms to disincentivise or punish caste-based coercion into sex work.”

Shiamala Baby, the director of Forum for Women's Rights and Development, a Tamil Nadu-based organisation, says that decriminalising sex work could help with a gradual social shift in acceptance of sex workers in the society also. “We have this false morality, where men will access sex workers, exploit them even, but also look down on their work. Social change takes time, but this could get them the rights and protections they need. A financial transaction for consensual sex between two adults should not be criminal,” she says.