Sunitha* has dropped out of school twice, most recently from a residential school in Telangana. Both her parents are garbage collectors working for the Greater Hyderabad Municipal Corporation (GHMC). When they leave for work at 3 am each morning, Sunitha is left in the care of her aunt, who sends her onto the streets to beg. Her parents return by 4 pm and, many times, the money she collects is used by them to buy alcohol.

Somewhere in the middle of all this, Sunitha managed to pass Class 5 at the Miyapur Government Primary School near her slum. She moved to the Miyapur Government Secondary School in 2017, but the new school was a little further away and her attendance ultimately slipped; she dropped out in 2017 as her family couldn’t afford transport. This year, in the month of March, Sunitha – now 11 years old – joined a residential school, far away from the domestic disturbances at her home. But just months later, she was back home, and once again made to beg on the streets.

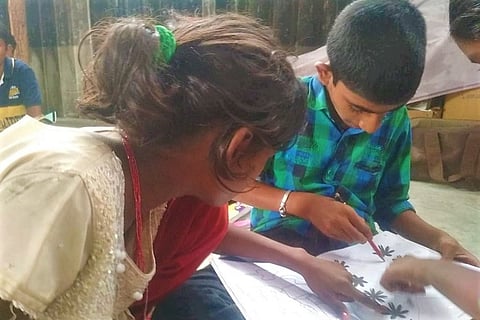

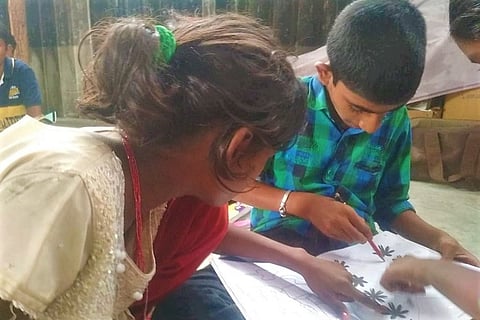

At the Miyapur slum where Sunitha and her family live, Yuva runs Chotu Ki Education (CKE), a non-profit bridge school that helps rehabilitate dropouts before they’re sent back to mainstream schools. Yuva was on her way to the school one day in the last week of July when she spotted Sunitha begging near a wine shop. Yuva was livid. “I had enrolled her at my bridge school after pleading with her family. We then got her enrolled with a residential school this year. She is a smart student. But her aunt came and took her away from the school in July. The residential school did not inform me nor did her family. I found her begging before the wine shop and brought her back to the bridge school,” Yuva tells TNM.

Bridge schools like Chotu Ki Education act as informal schools for children from slums who have dropped out, so that they can brush up on basics before they return to regular schools. But many of these children often end up going back to child labour as the government scheme that’s meant to help them, the National Child Labour Project (NCLP) under the Child Labour Act, is flawed, say experts.

Zero follow-up

One of the biggest flaws of the scheme is that states have no way of knowing if children who have been pulled out of child labour and enrolled in schools have dropped out again. The schools operated under the Centre’s NCLP rarely follow up on individual cases and they do not share data with the state either, allege educationists.

Further, schools that operate under the scheme are poorly funded.

About 100 meters from Chotu Ki Education’s school is another informal school bridge school run by the non-profit Swachh Society. This school has 40 students, and provides vocational training, mid-day meals, health check-ups, and a stipend of Rs 400 to each student per month for a maximum of two years. However, the funds from the Union government allegedly don’t come on time and Swachh India has to pay the staff and the stipend out of their own pockets.

What’s more, non-profits get discouraged from making use of the scheme because of its issues – namely that the scheme is limited to child labour victims. Yuva, who has not yet enrolled her non-profit under the NCLP scheme, says, “Not all the 22 children enrolled in my school are from child labour background. Some of them were found begging, others are students who drop out due to personal reasons. I am hesitant to join under the scheme as it only applies to a narrow definition of child labour.”

For instance, 11-year-old Sapna was a former student in a bridge school that used to run in the Miyapur slum. The school had mainstreamed her by enrolling her at the Miyapur Government Primary School; but soon, she dropped out again to take care of her newborn brother. Her mother, K Jaya, says she didn’t have a choice but to take her daughter out of school again, “There is no one to help watch the baby. We have debts and both my husband and I have to pay them off. The debtors started coming home and so I too had to start working.”

Jaya, who works as a domestic worker, says she tried to enrol her daughter back in school but couldn’t as Sapna had lost a few months of the academic year. “They asked us to enrol next year,” she says.

Sapna is currently at CKE, and will soon be enrolled with a residential school.

What is NCLP?

Launched in 1988, the National Child Labour Project aims to rehabilitate children rescued from child labour conditions and eliminate all forms of child labour in India. It is currently the only such scheme that focuses on child labour rehabilitation in the country. The guidelines for the scheme were revised for the first time in 2016, when the Child Labour Act was amended.

Under the amendments, the scheme prohibits children up to 14 years from working in any form of employment or labour force, while those between the ages of 14 and 18 are prohibited from engaging in hazardous occupations as per the Schedule of Hazardous Occupation.

NCLP is run by the Union Ministry of Labour and Employment and is enforced through individual states’ Labour Departments and the District Project Societies (DPS) that function under them.

The Centre claims to have identified 1,41,769 children involved in child labour across the country, with 70,873 of them currently enrolled in bridge schools referred to as Special Training Centre (STCs) under the scheme. The Centre claims that since 2017, about 48,046 children have been introduced back to regular schools from bridge schools. But no one seems to be looking at whether these children are continuing in school – at least not in Telangana.

The scheme is mostly run through non-profits that already run bridge schools for all dropouts and not just children rescued from child labour.

The cycle

B Narasimha runs three bridge schools under the NCLP scheme through his non-profit Swachh Society. He started his third school at the Miyapur slum with 40 children in March 2019, but says he has been facing delayed payments from the Union government for many years. Despite the fund crunch and the payment delays, 114 proposals for bridge schools were clocked until June this year.

“I pay the staff salaries out of my own pocket, we get donations and that helps us stay afloat. The funds from the Union government come once every three to six months,” says Narasimha.

Pointing out that the Union Budget for 2019-20 presented this July cut funding for the NCLP by 16%, Narasimha says he is concerned about further payment delays.

The delayed payments have resulted in most non-profits steering clear of the scheme, says Varsha Bhargavi, the state coordinator of the State Resource Centre for the Elimination of Child Labour in Telangana. She also oversees NCLP implementation in the state.

“The funds get delayed and so non-profits don’t want to be part of the scheme and run STCs. Another rule is that you have to be enrolled with the DARPAN portal for non-profits to become eligible for the scheme. Many grassroot level non-profits who do the real work cannot enrol with DARPAN due to digital illiteracy and internet connectivity issues. They are thus unable to enrol in the NCLP scheme,” she notes.

The inherent flaws

Several non-profits in Telangana offer residential schools for children rescued from child labour and school dropouts, such as the MV Foundation. Apart from them, the state government also operates residential schools that act as bridge schools for dropouts. Until 2016, the Union government provided funds to non-profits for the residential facilities, but the revised guidelines now only allow day schools under NCLP.

Non-profit organisations that offer bridge programmes and operate outside the NCLP often combine all school dropouts in one programme, as CKE does. The NCLP, as per its guidelines, is only for children rescued from child labour and can be set up only where the state has no bridging school.

The guidelines also state that an NCLP can only operate if more than 15 children are identified in a mandal, which cripples the scope of the scheme, Varsha says. “God forbid if the survey before setting up an NCLP shows only 14 child labour cases in a mandal. Then the NCLP school cannot be opened. There is no scope in the scheme. Those children are supposed to be rescued but are being left out and if there are no bridge schools run by the state in that mandal or district, then those children are lost,” she says.

In 2017, the Union government launched the Platform for Effective Enforcement for No Child Labour, or PENCIL, as a monitoring and reporting system for child labour rehabilitation, as mandated under the amended Child Labour (Prohibition & Regulation) Act, 1986 and NCLP scheme. With the launch of PENCIL, all NCLP-related data, such as enrolment, attendance, personal details can be accessed online – but only by the DPS and the bridge school principal. However, the state has no access to it, says Gangadhar E, Joint Commissioner, Telangana Labour Department.

All data related to the child thus gets tracked through PENCIL. “There used to be no monitoring before, it’s a lot better now. However, the portal can only be accessed for data entry and is directly monitored by the Union government. There is also an SRC account on the PENCIL portal but no access to the data on children at the bridge schools. We have requested the Ministry of Labour and Employment for full access,” says Gangadhar.

Having access to the data will help the state departments to better monitor if a child who has been rehabilitated through the scheme drops out of school again, he says.

When asked if all the children at the Swachh Society school at Miyapur are child labour cases, Narasimha says, “No, any child who has dropped out the school has been treated as a child labour case. There is no effort from the state or from the Union to keep the child in school. If ever we keep track of a child, it’s through our personal involvement.”

The Ministry of Labour is yet to respond to queries regarding NCLP.

Dropping out from bridge school

Twenty-year-old Yadhamma dropped out of school years ago, and spent most of her childhood working as a domestic worker. She now attends the Chotu Ki Education bridge school, though she’s not officially enrolled. She only wants to learn as much as she can.

“I want to study and escape from this place,” says Yadhamma, who is trying to avoid being pushed into marriage. No NCLP scheme school enrolled her while she worked as a domestic worker earning Rs 500 per residence.

The bridge school under NCLP run by Swachh Society would be the second school to operate at the slum. The first school closed down after its task of enrolling 20 children to the nearest government schools was completed in 2017. At least five boys from that batch would drop out of schools again and get enrolled at CKE before going back to regular schools.

Though the guidelines for the NCLP mandate regular check-ins and involvement of the community through parent-teacher meetings, it’s rarely followed by non-profits enrolled with the scheme. The only time a non-profits is quizzed on it is when they fill out a feedback form to the DPSs. Both non-profits working in the slum do not accurately know how many children are out of school from the slum, and neither does the state nor the Centre.

Narasimha says he has helped enrol over 4,000 children in the last decade – but admits quite a few of them have dropped out. “I didn’t keep an exact count,” he says. This is despite the fact that schools under the NCLP are supposed to keep track of the child for a year.

At the Miyapur slum, he is in the process of enrolling children who have dropped out of schools and have gone into begging and rag-picking. He goes door-to-door, the Rs 400 stipend a key attraction for parents to send their children to his bridge school.

“The task is not over just after enrolling them into a government school. It’s important that we follow up on each case,” says Yuva, who also goes door-to-door requesting parents to allow their children to attend her school. “The community needs a bit of coaxing to send their children to school. If we don’t give individual attention to each case, there is no way to keep track of the children and their education,” she adds.

The amendments to the Child Labour Act and the revision of guidelines has opened new flaws in the scheme.

“With the dilution of the Child Labour Act, the state surveys now do not take into account those children working in family enterprises, bonded labour and non-hazardous work environments. This affects the quality of surveys on child labour in Telangana,” says one official with the Labour department.

Whose job is it anyway?

When asked if the Labour Department is responsible for ensuring that the rehabilitated children in the state do not drop out of schools, the Labour official responds, “It’s the duty of the school principal to report to the Education Department if any child has dropped out of the school. The Education Department should be monitoring this.”

Varsha alleges that the Labour Department is ill-trained to handle matters related to education. “There is a seamless integration of schemes with other state departments under NCLP. The school curriculum and the mid-day meal scheme is also provided by the Education Department. The Labour Department officials can handle child labour rescue but the welfare should be ideally run by the Women and Child Welfare Department and the Education Department. It’s just common sense,” she says.

Issues faced by community compound dropout problem

The Miyapur slum sits on the Mumbai Highway in Hyderabad and holds approximately 600 homes. A vast majority of the residents there work as garbage collectors on contract for the GHMC, while the rest are involved with the informal waste segregation and rag-picking industry of the metropolis. Come 2020, the roughly 60 children at both the bridge schools in the slum – CKE and Swachh Society – will get enrolled in state government-run residential schools or private schools, but not all of them will stick around.

Like garbage collectors in many parts of the country who have to deal with unsanitary and inhumane work conditions, the community in Miyapur too copes with the stench and garbage with the help of alcohol. Yuva says many people in the community have an alcohol addiction problem, which is one of the issues that affects the education of the children.

“Most of these parents go to work at 3 am for the GHMC and don’t return until evening. There is no one to take care of the children until then, no one to push them to go to school, so they roam free. They end up working as rag-pickers, and most of them end up begging,” Yuva alleges.

There are at least three wine shops near the slum, but the illegal sale of homemade toddy is a larger concern. “There is an addiction problem in the community,” says B Vimala, a community leader in the slum who helped the non-profits find a place to build their schools. “Many houses in the slum run toddy shops. After work, both the husband and the wife start drinking. Many of the children also start drinking from a very young age,” she adds.

When TNM met with Sunitha’s father, Mallesh, he says, “I want to send my children to school. I want them to succeed, but there is pressure from the family that when the girls reach maturity they should be confined to their homes. My older daughter dropped out of school and will get married soon. But Sunitha, I want to delay her marriage at least until she is 20.”