(This story is a part of The News Minute's Dalit History Month series)

When one thinks of BR Ambedkar, perhaps the first image that comes to mind is one of him looking at the viewer, or perhaps to the side, staring into the distance. But he always dressed in blue. Despite these images which readily come to mind, Ambedkar has not quite been a subject of art in the same manner as images of him have been used to lay claim to public space. That’s where two artists, influenced by his ideas and by their discomfort with the caste system, come in. One of them told Ambedkar’s story in a Madhubani painting and another represented him in the colours of rebellion.

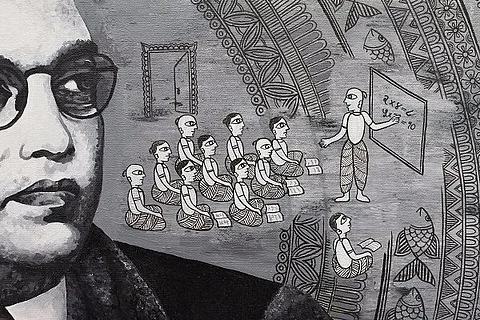

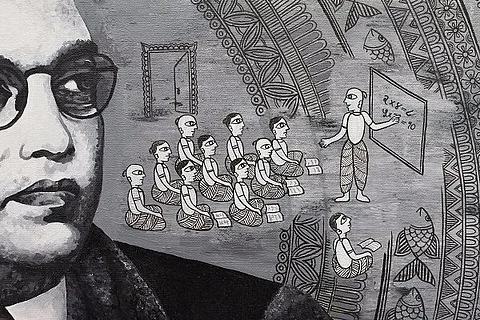

Delhi-based Malvika Raj took one-and-a-half months’ time to paint Ambedkar’s life in the Madhubani form, but the man has always been a part of her life thanks to her father who often talked about Babasaheb.

Stories about Ambedkar that she heard from her father and the ones she discovered herself, found their way into a Madhubani painting which was presented to the University of Edinburgh, on the occasion of Ambedkar’s 125th birth anniversary. It is now displayed there.

On a canvas of around 3.5 by 2.5 feet, Malvika drew a portrait of Ambedkar who appears to be looking at his life: sitting separately in a classroom, meeting Gandhi, receiving the Buddhist deeksha, his wedding, the Mahad Satyagraha and more. The scenes from Ambedkar’s life have been intricately drawn in grey, an emphasis on the troubles of his life against a peaceful, white background.

As a category, the term Dalit art is not yet accepted in contemporary art. Faculty member at the Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda Deeptha Achar says that the category is necessary. In a 2015 interview, she told The Hindu: “…one function of a category such as Dalit art is to underline the idea that the apparently unmarked or caste neutral category of modern Indian art is also constituted by caste — its concerns, its thematics, its understanding and representation of social structures have a caste dimension… A category such as Dalit art would problematise the caste dimensions of apparently unproblematic terms.”

For Malvika, being Dalit has always been part of her identity and it reflects in her art. “As a Dalit, what I saw when I was growing up… My father would tell me ‘It’s ok. These things happen.’ He would tell me how to fight back.”

Growing up in Patna, Malvika studied in a Hindi-medium school, but it was the books on Ambedkar and Buddha in her father’s library that captivated her. But it would be long time before she became an artist and engaged with Ambedkar through it.

Malvika worked for two years as a fashion designer in Delhi after graduating from NIIFT in Mohali, Chandigarh. In 2010, health concerns forced her to temporarily return to her hometown, where she finally gave to her desire to learn Madhubani painting. For three months she trained under Ashok Biswas and then she worked out other ways to continue learning the art form.

When her work began to be exhibited, it was criticized for breaking from tradition. But the nature of objections suggests that it had more to do with the fact that possibly, Malvika’s art was a reminder of the existence of a Dalit narrative.

One of Mavika’s favourite subjects is Buddha. Influenced by Ambedkar’s ideas, she depicted Buddha as a teacher and spiritual leader and not the tenth avatar of Vishnu as he is positioned in Hindu mythology. In a series of around 40 paintings she has depicted his teachings and scenes from his life.

“People said I should have painted the Ramayana. But how can I paint the Ramayana with love when I don’t believe in it? I believe in Buddha,” Malvika says.

While this was early in her career, two years after she learned the art style, she encountered other undeclared ways which caste is reflected in and is perpetuated through art.

Around 2011 or 12, she visited Jitwarpur village, Samastipur district, to meet village women who keep Madhubani art alive. She consciously chose to establish contact with the Dalit tolas (areas of the village) first, as she was anxious about how upper caste people would treat her.

She learned that there was a difference in the ways Dalits and upper caste people practiced the art. Dalit artists drew a single outline while upper caste people used double outlines against the white background which gave a whitish appearance to the lines, Malvika said.

During the trip, she also visited a practitioner of the Tantric art form, who showed her his work in his house. “I was curious. I asked him if he would teach the art to me, and he said ‘We don’t teach it to everybody… Bad things happen to others if they learn and practice the art… We have to chant mantras, so we don’t teach it to everybody’. The obvious implication was that it was to keep it within the caste,” Malvika said.

The visit to this house also brought home to her how privilege and the resulting opportunities and networks helped upper caste artists establish themselves in the art world and in terms of financial remuneration.

“The sons and daughters of upper caste people have access and connections in the art world, from which they directly benefit. But the people who are oppressed and trodden upon, they get nothing for their art; the middlemen take the cut,” she said, referring to the Dalit artists of Jitwarpur.

While Malvika chose to caste-ise art and infuse it with Dalit narratives, R Rajesh, a graphic designer, could not understand why some people were treated unequally.

Born into an upper caste family, Rajesh witnessed discrimination in his village Edathanur, which is near Thiruvannamalai. “When I was in the eighth standard I once asked my grandfather, ‘Isn’t everyone equal? Why are they being kept separate?’ I would not get any real reply, only be shouted at. ‘You don’t know anything about this. Get out,’ they would say.”

When he was in Class 9 or 10, he discovered Ambedkar’s writings. “I had interest in him then itself. So I grew up wanting to do something about it. I had even done some paintings on the situation in my village then.”

As a child, he would graze the cows in the evening. He practiced painting to while away the time. That dabbling in art is his livelihood today – he is a designer with a national daily in Madurai.

His digitally created portrait of Ambedkar, was displayed in an exhibition on caste held at the University of Edinburgh as a part of its Dalit History Month celebrations.

“Mostly different shades of blue are associated with Dalits. I used red to represent Ambedkar’s revolutionary spirit, the fire in his mind.”

For both Malvika and Rajesh, engaging with caste in art, has brought some uncertainty and criticism.

“The things I wanted to say, I have said through my paintings. If I say it with words, I don’t get that much respect. But if I paint the same things, people enjoy it, appreciate it and give me respect,” Rajesh says.

(With inputs from Rakesh Mehar)