It’s a sultry morning at the Kotturpuram Tree Park in Chennai, the heat palpable even at 8 am. The park, which houses over 600 indigenous and naturalised trees, was enabled by the city-based NGO Nizhal, in association with the Corporation of Chennai.

Amidst the burgeoning trees beside the walkers’ paths and the chirping of birds, Shobha Menon of Nizhal talks me through the volatile situation of Chennai’s green cover.

Pointing out the neer maruthu (Arjuna tree), that has apparently been used since the 7th century for its cardio-protective properties, and the Purasu tree, which gave Purasawalkam its name but of which only one remains in the area, she explains that many such trees “that have been a part of our culture and tradition, have been vanishing because of indiscriminate planting.”

This issue is expounded upon by Dr Jayshree Vencatesan, Managing Trustee at Care Earth Trust, a self-funded NGO which seeks to conserve biodiversity for human well-being through research, advocacy and capacity building.

She says, “We have greenery which is very typical to (Chennai's) landscape - a coastal landscape - which we need to promote. It is a fact that many foreign species have come here over the years, through gardens and such, which have become naturalized. It is when these species run amok and cause a detrimental effect on the habitat itself that they are designated as invasive alien species. These species have to be removed, because they can cause a lot of harm to the native biodiversity. You cannot push an argument where you say you will promote native biodiversity (without removing) invasive species.”

She adds that “selective disappearance [of vegetation] is what has categorized Chennai. Most of the plants that we find in Chennai are historically associated with wetlands, which have been compromised."

At the Tree Park, Shobha excitedly walks ahead to show me the sarakondrai, or Indian laburnum, with its golden yellow flowers in full bloom. But it isn’t all rosy - along the way, she explains that the park is almost wholly maintained by Nizhal, raking up dried leaves to act as compost and watering the trees, with little support from the Corporation.

The sarakondrai tree at Kotturpuram Tree Park

“We rely on one hand pump to manually water the entire park,” she says. This leads to some unfortunate outcomes - she shows me an Azhinji tree, sometimes used for anti-rabies treatment, that’s dried up due to lack of attention.

As we talk about the government’s role, we encounter a Corporation caretaker who has been lax in his duties. “This is how supportive the government’s been,” she says exasperatedly. Shobha also points to the lack of progress on The Tamil Nadu (Urban Areas) Regeneration and Preservation of Trees Act, a draft of which Nizhal submitted to the state government more than two years ago. The Act sought to “make better provision for caring of trees and increasing tree cover in the state,” but its stalling is indicative of the lack of political will to prioritise the environment.

This lack of resources multiplied across the city, combined with the aftermath of Cyclone Vardah, has had dire consequences for Chennai’s green cover. According to a joint survey undertaken by Nizhal and TEEMS India after Vardah in Ward 176 of the city, comprising Arunachalapuram, Sastri Nagar, Vannanthurai, Besant Nagar, Kakkan Colony, Urur Kuppam, and Elliots Beach, 16.36% trees were damaged and among these 9% were uprooted.

An observation that reflects the importance of planting indigenous species of trees, as well as the conservative attitude to be adopted towards other species, was also revealed through the survey - among uprooted trees, 22% were indigenous species and 77% were exotic.

Among wind thrown trees, 60% were exotic and 39% were indigenous. The naturalized Copper Pod trees were the most vulnerable and got uprooted in the highest numbers, followed by Elephant Ear Pod tree. Shobha explains that “trees such as the gulmohar and the raintree are shallow-rooted, so they keel over - it’s alright in a big park, but not when you plant them in a constricted space such as a roadside.”

The loss in the city’s green cover is significant - besides Vardah’s impact, Dr Jayshree also explains that “the green nature of the city is being compromised largely because green areas are being converted into urban spaces. The agrarian areas, such as paddy fields and coconut and mangrove grooves, which were buffering Chennai are being lost; essentially you're losing everything that's green, and it's very stark. This kind of loss is greater in new habitations, due to the expanded city. Inside Chennai, it's nearly bare, besides the forest areas in the city or in institution campuses."

She bemoans the fact that “Chennai has lost its resilience. It's not just about the ability to bounce back, but the time taken to bounce back - that has been severely compromised.”

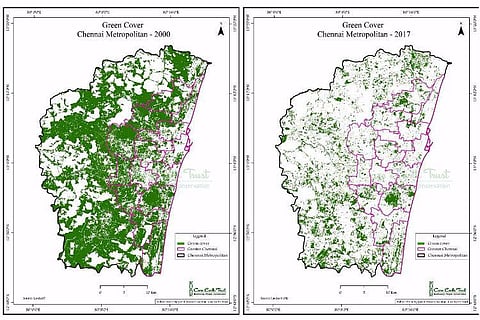

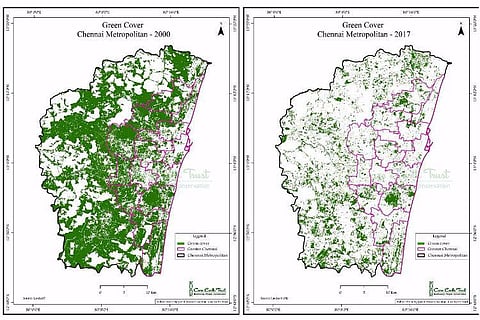

The dire straits Chennai is in is corroborated by survey maps of the city’s green cover, undertaken by the Care Earth Trust - the difference between 2000 and 2017 is shocking, and indicative of the alarming trend in loss of vegetation.

So what’s the way forward for Chennai’s green cover?

Dr Jayshree believes that “the only way Chennai will revive itself is if you have larger engagement of people and a respect for science-based facts.”

She stresses that total restoration is impossible, and that reasonable benchmarks need to be set, explaining that “you abuse the environment so much, that immediate recovery is not possible. You need to wait it out."

She reminisces about the restoration and conservation efforts taken for the Pallikarnai marsh as an example of what can be achieved through the confluence of involved parties. “It was science, activism, community work, and media outreach.” Currently, however, “that kind of galvanizing is not happening."

According to Shobha, meanwhile, the answer lies in citizen participation. “Greening is an important civic issue that needs to be looked into for your own sake, not just as something that the government or NGOs should be doing. We need more citizen movements - citizens who are caring and responsible, and not just those who say I pay my taxes. It’s about being proactive about your support.” Given Chennai’s population, she wonders why are there so few concerned citizens. “I think it’s a shame.”

With our walk around the Kottupuram Tree Park wrapping up, Shobha asks, “why are we taking trees for granted?” Given the condition of Chennai’s green cover, and its ecological implications, it’s clear that the city can no longer afford to ignore its responsibilities towards the environment. As I leave, she offers a pointed warning to the city’s residents - “If the trees aren’t there, they’re just paving their way to hell. Look at how hot this summer is.”