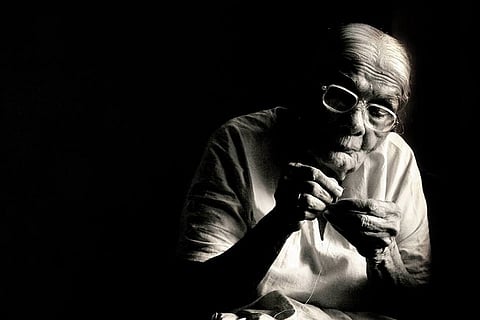

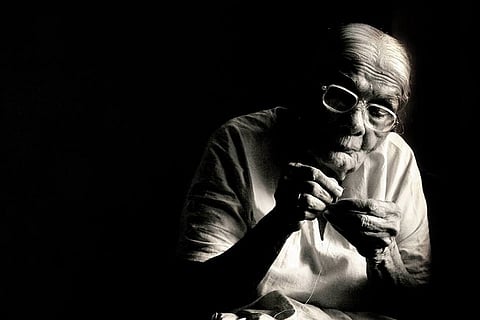

Babitha’s big eyes widen and fill up as she recounts an old childhood tale, about the days after her grandmother moved into their Thiruvananthapuram house from Mavelikkara. She has written that tale somewhere, one that her friend Abhirami Girija Sriram found too telling. The two of them had then been collecting stories of grandmothers from writers they knew, and those they reached out to in several corners of the world. A book was in the making. A greyish little book that has 104-year-old Mariyamma Xavier waving on its cover – Salt & Pepper & Silver Linings: Celebrating Our Grandmothers – the title read, all in small letters.

“That on the cover is the grandmother of Seema Krishnakumar, one of the 44 contributors of the book – and hers is a photographic essay,” Babitha Marina Justin says. Babitha’s grandmother too is a Mariamma, but the story she put in the book is slightly fictional – an extract from the novel she’s just finished – Maria’s Swamp. “Abhirami advised that I don’t include the first story I wrote because it was too telling. I too later realised that’s so.”

Babitha and Abhirami have known each other for long. Babitha is a professor at the Institute of Space Science and Technology and Abhirami is chief sub-editor with Frontline magazine. They are contemporaries and went to the same university. It was a Facebook post that Abhirami wrote three years ago that gave Babitha the idea of an anthology. Abhirami wrote on June 7, 2016 about her grandmother whom she called Sachamma. Babitha had then been writing her novel in which her grandmother played a big role.

Babitha

“She superimposes on my life,” Babitha says dreamily, of her late grandmother. She snaps out of it and says, “A lot of women would have bittersweet memories of their grandmothers, of lives untold. Many grandmothers just lived and died as housewives and mothers and, of course, as grandmothers. We wanted to historicise them, we wanted ‘her stories’ to be written.”

They reached out to the writers they knew and went on writers’ platforms to reach out to others. “It had to be representational – we wanted writers from across the country, and from across the world,” Babitha explains.

More than half of the authors are from India – including Annie Zaidi, Arundhathi Subramaniam, Jaishree Misra, Khyrunnisa A, Sharmila Ray, Suneetha Balakrishnan, Tishani Doshi, Meera Nair among others. Writers from outside – Nigeria, Canada, Europe – have also been quite prompt in sending their stories much ahead of time – writers like Gayle Brandeis, Gloria Mindock, Kathleen Kilcup, Maia Kranidis, Unoma Azuah, among others.

Babitha and Abhirami hadn’t planned it but somehow the stories that came had a kind of cultural flavour of the places they came from. The writings came as stories and poems and of course the photographic essay Seema gave. “Seema’s grandmother is someone who has seen both the big floods of Kerala – 1924 and 2018,” Babitha says.

In her own partly fictional tale, Babitha calls herself Maria, posts a photo of the young Maria and granny Mariamma, and writes about an episode involving a certain lamb curry and six children. She describes her grandmother as sweet and short-tempered but a couple of lines she said makes a difference to little Maria. When little Maria asks Mariamma, “How come you are so fair and I’m so dark?” the older woman says, “God had an oven in which he used to bake human beings from a mould. When he put his human-shaped dough in his oven, Indians were baked into a perfect brown. Some were lighter and some darker. But beautifully brown either way.”

Abhirami, the editor who did the desk work (and Babitha calls herself the one on the ground), didn’t write a story – only her three-year-old Facebook post is on the first page. But her sister Aishy has an entry. Aishwarya Sriram was diagnosed with autism when she was three, and has a daily journal that she writes in Tamil. Her mentor Lakshmi Mohan has given an account of Aishy’s relationship with her grandmother Gowrimma, very dear to her but with whom she has the occasional tiff. But when it comes to people going to umaachi (Tamil baby-speak for god), Aishy would say, “Aishy not going! Be here only! Gowrimma be here only!”

Gowrimma, Aishy's grandmother, with the book

If that story touches you, another would amuse you (Khyrunnisa’s entry is about how she sniffed her Nani’s powdered tobacco as a child and made the grandmother guffaw watching the ‘stellar effect’ it had on her), a third would make you think hard.

One of the most powerful stories comes from Vaikhari Aryat, a Dalit feminist and research scholar from Hyderabad University. “It gave the punch that the book needed,” Babitha says. Vaikhari writes about her grandmother Janaki and the mothers before her, whose stories upset her much.

I learned for instance that my great grandmother and her sisters were hunchbacked from a lifetime of agricultural labour and from not being allowed to stand upright in front of the thampranmar, the “lords”.

She writes of how the great grandmothers refused to sit on waiting chairs and chose the floors instead, or stayed away from restaurants because they could not believe they would be allowed to sit and eat from plates inside.

Vaikhari writes, “I am the granddaughter of all the women you made to stand outside your history books. I inherit my strength from their memories, and I will continue writing their stories.”

The book ends with Vaikhari’s story – it is in alphabetical order of the authors’ first names – and begins with Aarcha Mahendran, whose grandfather was the grandchild of the social reformer Ayyankali.

It has not all been easy, collecting these stories and making sure it is representational. There are also the differences between the two editors when it comes to bringing the book out. “We would bicker and say that we would end up fighting it out. She is this perfectionist and I go by intuition. There would be stories that she likes and I wouldn’t understand at all, and there are ones I like but she would find clumsy,” Babitha laughs.

But in the end, both of them and all the writers who contributed are happy to hold this little grey book of grandmothers in their hand.