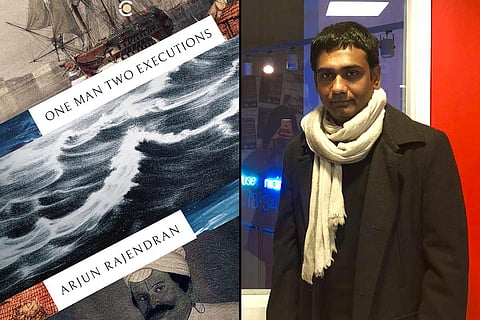

Arjun Rajendran, author of the poetry books Snake Wine (2014), The Cosmonaut in Hergé’s Rocket (2017) and Your Baby Is Starving (2017), is jubilant about the publication of his new volume, One Man Two Executions, with Westland.

Of the three sections this book is divided into, the first is set in French colonial Pondicherry during the Carnatic wars. As part of his research, the poet immersed himself in English translations of the Tamil diaries written by Ananda Ranga Pillai (1709-1761), who used to work as a dubash or interpreter for the French governor Joseph François Dupleix.

Here are some excerpts from an interview.

My father is interested in numismatics and history. In 2015, when he came across online translations of Pillai’s diaries into English, he asked me, “Do you know this guy who has written copiously about Pondicherry in the 18th century?” I had no clue. I started looking into the diaries only in 2017. I found them rich and detailed but took a while to figure out how to approach them as material to make poems. History is only a launchpad for me to create ambience and images. I am not a historian and I’m free to take creative liberties.

Invaluable! Pillai was not only an interpreter to the French governor Joseph François Dupleix but also in charge of espionage. Through his diaries, we learn about power dynamics between the French, English, Danish, Portuguese, Mughals, and Marathas -- all of whom were vying for the Coromandel coast because of its strategic significance. We get to know about ships that no longer exist, coins minted during that time, the role astrology played in people’s lives, weapons used, price fluctuations during wartime, the practice of slavery, physical segregation between ‘caste Christians’ and ‘casteless Christians’ within the church, and more.

I read the diaries several times, and made notes whenever I came across descriptions of events that struck me. Pillai writes with a sense of self-importance. He isn’t witty or entertaining, so reading was certainly a challenge. Each poem took almost a month to write. People who read my initial poems found them dense, so I realised that I needed to go easy on the history. I introduced more imaginary elements. Three of the poems in the first section of the book -- “guzzerati girl, riverbank,” “The Lascar’s Wish,” and “Pirate” and a few other poems -- are about someone I love. I have inserted her into the 18th century. This way, the first section segues into the second, “The Girl in The Peapod".

During Pillai’s time, there were two methods of execution -- death by firing squad for military officials, and death by hanging for civilians. It was believed that, if the rope used for hanging gave way and broke, God had pardoned the person. The priest was called in to give his blessing, and the person was exonerated. In this poem, the priest defies the custom by not absolving the criminal. He overrules God’s decision, and his own duty to pardon. He demands that “the almost-hanged” be hanged again.

I had an emotional moment when I read about an incident, which is referenced in my poem “Desecration.” Christian priests in Pondicherry, thanks to the encouragement of the French governor’s wife -- who was a fanatic -- threw faeces in the courtyard of a Hindu temple. It’s not mentioned in the diaries but it’s a well-known fact that Hindu priests were unwilling to get their hands ‘dirty’. It’s assumed they expected the filth to be cleansed by the oppressed castes, who were usually not allowed to enter the temple. They were brought in to do the job but worshippers would not even look them in the eye because they were considered a polluting influence. What a conundrum!

Pillai was an affluent man, so the occasion would demand an enormous ceremony. I would wear opulent robes, and travel on an acheen horse and palanquins bearing gifts to meet him. At that time, writing was mostly done on palmyra leaves. A book printed on paper would be a treasure even for a man of his standing. It would be brought in a special carriage with great fanfare. Guns would be fired to mark the occasion. There would be dance and music, perhaps even a feast.

Stirling is a medieval town in Scotland with a long history of resisting the English. It was a fortunate coincidence that I was writing about another power doing the same in Pondicherry. Stirling gave me a lot of space and time to contemplate and write. However, I could hardly meet any scholars of the historical period I was interested in. At the university, professors’ pensions were being threatened; many of them were protesting and the campus was deserted. Going to the National Maritime Museum in London helped me appreciate the complexity of workmanship that goes into ship-building. Looking at the meticulously crafted models, I imagined those vessels sailing in the ocean. It bolstered my creativity.

Frankly, it didn’t add much to my research. I spent only three days there. The Pondicherry I visited was vastly (and predictably so) different from the colonial town that Pillai inhabited. His house, now converted into a museum, isn’t well-maintained. The room where he used to write and his diaries were out of bounds for visitors. I saw some artefacts from Pillai’s time, most importantly his portrait commissioned by the trader he saved from ruin. And I met his descendants -- including the spouse of Ananda Ranga Ravichander -- who were proud of their ancestry. Who wouldn’t be?

All images courtesy Westland.