On June 9, Karnataka Medical Education Minister Dr K Sudhakar’s tweet eulogised the ‘Bengaluru model’ of fighting COVID-19. In his tweets, he wrote about about how the Bengaluru model beats the New Zealand model. In a graphic he shared, Dr Sudhakar said that while New Zealand had a total of 1,150 cases (at that point), Bengaluru had only 450 cases; and the COVID death toll too was 9 less than that of New Zealand.

Sudhakar, at the time, was the minister in-charge for COVID management, along with Health Minister B Sriramulu, as per instructions of Chief Minister BS Yediyurappa.

Though what Sudhakar wrote was true at the time and the city had received much praise, things have changed drastically over the last weeks. Just a fortnight later, on June 23, Bengaluru emerged as a hotspot, racing to match the numbers of cities like Chennai and even Mumbai. Meanwhile, according to the New Zealand government, there have been zero cases reported in the last 24 hours (at the time of writing) and the number of active cases is 21. On the other hand, Bengaluru as of July 26 evening has 33,156 active cases.

— Dr Sudhakar K (@mla_sudhakar) June 9, 2020

The minister was not alone, his Cabinet colleagues, residents of the city, the Centre and even the media hailed the Karnataka government and the Bengaluru civic body’s handling of the pandemic.

So what went wrong? Why is it that, as on Sunday, Bengaluru features in the list of top 10 cities reporting the highest number of COVID-19 cases in the country?

A quick look at the number of positive cases reported show how flawed the city’s understanding of COVID-19 was.

With the first phase of unlock on June 1, 2020, there was a surge of cases across the country and in Bengaluru, they went up more than 10 times. At the end of June, the city had 4,555 cases, against 358 at the end of May.

In another two weeks, the numbers went up 5x to 20,969 cases in Bengaluru city on July 14. The surge intensified to 34,943 cases on July 19 and 36,993 cases as of July 22.

Insiders in the Karnataka government, who have kept close tabs on the progress, said that the much-hyped Bengaluru model was just a series of lucky coincidences. While other districts have fared far better, the capital city, with its myriad problems, has seen a steep rise in the cases over the last 30 days.

During lockdown 1.0 and 2.0, it seemed like the Bruhat Bengaluru Mahanagara Palike (BBMP) had managed to put in place the required infrastructure to fight the pandemic, if and when the numbers increase. From a ‘state-of-the-art’ war room at BBMP headquarters to creating additional, makeshift isolation centres if the government falls short of beds – it looked like they had it all in control.

But experts say they failed to work on something much more fundamental: committed data management. Sources in the civic body attribute the spike in Bengaluru’s numbers to BBMP’s inability to collect and analyse data which would establish patterns and clusters, crucial in curbing the spread.

When restrictions on movement were lifted and an inflow of people from other districts and states started, apart from cursory checks, no real-time data was collected.

With numbers being reported thus far on the lower side, officials who had initially been vigilant became less guarded, with the laxity showing its effect on the processes followed.

Another key area where the civic body failed, and miserably, is in contact tracing. The wait time for the result of a sample given for testing has increased to five to six days. And even after that, apart from a phone call from an official of the health department, a patient who has tested positive would have no instructions on what will follow for at least another four days. In the meantime, while patients are orally instructed to home isolate, there are no checks to monitor the same, according to sources.

During the lockdown, BBMP lacked foresight which meant that once the lockdown was lifted, they were left groping in the dark. They floundered in utilising the lockdown period to prepare for a time with fewer restrictions on movement of people, and exponentially higher chances of the virus spreading.

“When the lockdown was lifted, there was always a chance of greater movement and exposure to the disease. And once life went back to normal, people not following the precautionary measures of hand hygiene, physical distancing and masks has resulted in this spurt of cases,” said Dr Gururaj, Professor and Head of Epidemiology at NIMHANS.

“The numbers are not out of the blue. This was expected and this has happened and is happening all over the world,” he said.

“In Bengaluru, a lot could have been done better at different stages regarding the 4Ts – Tracing, Tracking, Testing and Treating. It is only now that the testing has significantly gone up, but with testing there is always scope for improvement. And this has been the constant recommendation to the government,” Dr Gururaj added.

On the issue of contact tracing, he said, “With more and more cases, contact tracing is very difficult and it may not be realistically possible to scale up manpower all of a sudden. So definitely this is a challenge and would need better coordination between different agencies.”

Dr CN Manjunath, state nodal officer for COVID-19 testing, and director of Jayadeva Institute of Cardiovascular Sciences and Research, had earlier told TNM that there were various lapses in the BBMP’s functioning in the June phase when the spike was observed, with the whole state going for Unlock 1.0.

Dr Giridhar Babu, an epidemiologist with the Public Health Foundation of India, who is part of expert committees both at the state and Union level, said testing and lack of resource optimisation was a major issue.

“The BBMP was taking too much time to arrange transport of patients from their house to the hospitals and sometimes even hours after the result was out. This delay of isolating the patients had exposed others to the infection. In terms of testing too, the government was recommended to do random testing, but to a large extent testing was limited only to symptomatic patients,” Dr Manjunath said.

He added that in closed places, even though asymptomatic patients may not sneeze or cough, they can be vital carriers of the disease and spread infection.

Another issue highlighted by Dr Babu is the sub-optimal utilisation of testing resources. Even though Bengaluru, unlike most cities in the country, has more than 20 labs, there was no uniformity in sending samples to private labs, And this led to multiple backlogs and further compounded the problem of cross infection.

He said testing at a microlevel was also an issue. “Due to lack of uniform testing across all areas of the city, there might be a wrong notion that some areas are less affected than others simply because of lack of testing. With undetected cases increasing, deaths might occur, or we may see super spreader events,” Dr Babu added.

The political cacophony in the Yediyurappa government has also had a ripple effect, resulting in the huge mess that Bengaluru’s fight against the pandemic has become. The fact that there are eight different ministers given charge of handling the pandemic has already been spoken about at length.

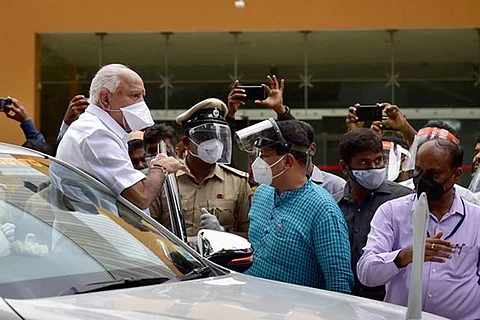

But such a decentralised approach was necessitated by the fact that Bengaluru Urban district was being handled directly by the CM so far. While all other districts had individual ministers and special officers appointed, Yediyurappa chose to keep the charge of Bengaluru with him, which meant that he could not focus completely on the city and its progress in fighting the virus as he had too much on his plate.

With no particular minister appointed for communication with the media with accurate updates, contradictory statements from ministers who would not shy away from speaking to the press despite having no information, only added to the chaos.

Insiders believe that the animosity between the two key ministers – Sriramulu and Sudhakar – who were not even on talking terms for several days as per sources, was amply exploited by bureaucrats. From giving blatantly contradictory statements even about the number of cases early on, to confusing the very direction that the city should take in battling the crisis, the two ministers botched up the road ahead efficiently.

This meant that the period of lockdown, which was meant primarily for the states to prepare themselves for the time when cases would rapidly increase, was wasted. And when the cases started increasing, with no proper planning and foresight, the government’s reactions were knee jerk.

Many in the BJP also believe that the Health Minister’s much-criticised remark of ‘only god can save us’ might have been a misplaced statement – but it’s not far from the truth.